Voting Rights: Past and Present

Voter Literacy Box

Plainfield Historical Society

Mountain Miller Relief Corp No. 158 Women’s Relief Corp

Plainfield Historical Society

With so much attention being paid to next week’s presidential elections, and with talk of voter suppression in the air, Plainfield Historical Society members thought it was a good time to highlight two artifacts in our collection that have connections to the ever changing history of voting rights, or suffrage, in both our country, state and yes, even in our town.

Because of the diligence of our local poll workers here in Plainfield, we can rest assured that our votes are counted and validated fairly, and will have a meaningful impact on who represents us. But that is not the case in many parts of our country this year, as reports of long lines, restrictive voter-ID laws, complications with mail-in voting and contested ballots, appear in the news daily. History shows us voter suppression is nothing new to our country – both in the South and the North – and from large cities to small, rural towns.

As always, the blue highlighted text are hyperlinks that will take you to a site to learn more.

Rotating Literacy Test Ballot Box

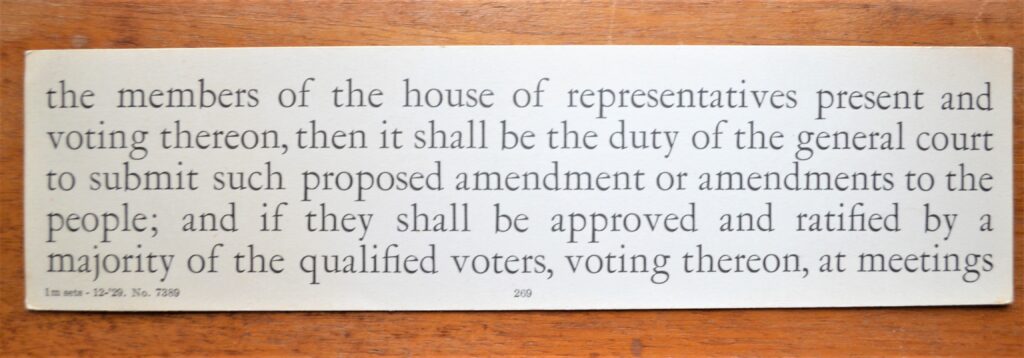

This item is a rotating, oak box that contains small cards with excerpts from the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. These cards would have to be read by potential voters to prove they were literate. If a person couldn’t read from the card they were not allowed to vote. The box would spin and voters would be handed a slip of paper with a section of text on it, making pre-memorization nearly impossible. This practice is what was known as a “literacy test.”

Massachusetts was one of the first states to adopt a literacy test to vote, implementing the policy in 1857. Over the course of the next fifty years the United States’ Congress tried to make a federal law requiring literacy tests for voting but it was never successful. Literacy tests were permanently banned nationwide following the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This act was signed into law on August 6, 1965, by President Lyndon Johnson. It outlawed the discriminatory voting practices adopted in many states after the Civil War, both in the North and South , including literacy tests as a prerequisite to voting.

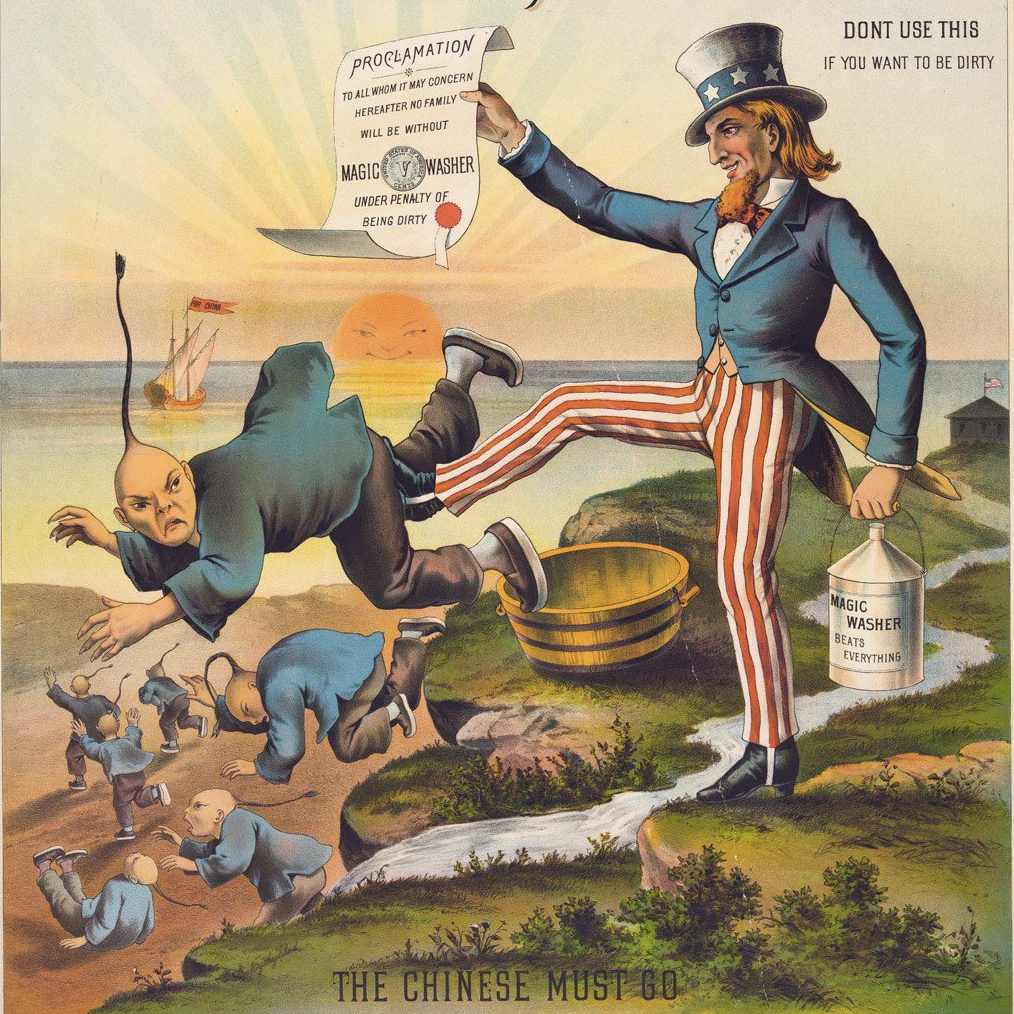

Why literacy tests? During the period between 1850 and 1950 millions of immigrants were arriving to the United States and Congress started passing laws, such as the The Immigration Act of 1891, and the Chinese Exclusion Act, and even implemented a poll tax for voting. These laws achieved the desired effect of disfranchising African-American and Native American voters, as well as poor whites who were recent immigrants. A strong sense of nativism sweep the country.

Between 1850 and 1930, about 5 million Germans migrated to the United States, peaking between 1881 and 1885 when a million Germans settled primarily in the Midwest. Between 1820 and 1930, 3.5 million British and 4.5 million Irish entered America. Before 1845 most Irish immigrants were Protestants. After 1845, Irish Catholics began arriving in large numbers, largely driven by the Great Famine. Many of these immigrants were unskilled and fear and prejudices began to grow across our country. At this time only white, literate men over the age of twenty-one had the “protected” right to vote. Fear of this influx of millions of immigrants led to the formation of new anti-immigrant, nativist parties, including the Know Nothing party, in which Massachusetts played an important and unsettling role.

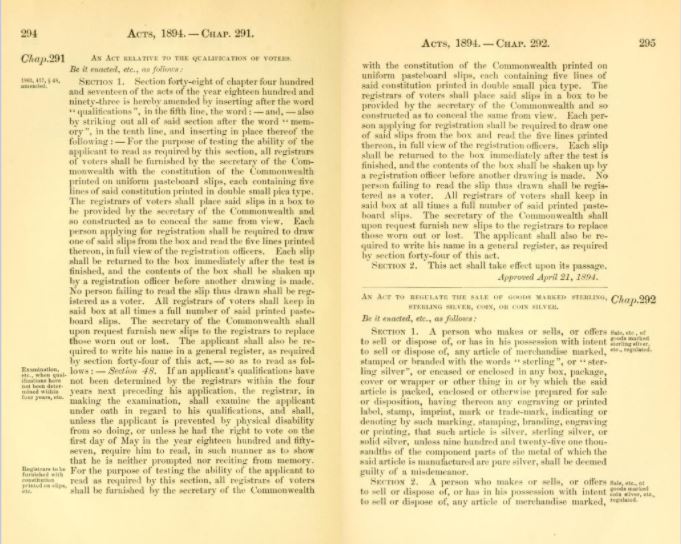

Connecticut and Massachusetts, where the reaction against suffrage extension was strong, were the first states to act on the policy of adult male white suffrage. In place of property qualifications, literacy restrictions appeared. The purpose of these restrictions set up by Connecticut in 1855 and Massachusetts in 1857 was to bar “ignorant” immigrants from the voting class. One of the popular methods of administering the literacy test outside of the Southern states was in operation in Massachusetts. The applicant for registration draws a pasteboard slip from a box. He must read the five lines printed on the slip and write his name in a register (Mass., Acts and Resolves (1894), chap, 291. sec. 1)

The Causes of Know-Nothing Success in Massachusetts

Author(s): George H. Haynes

Educational Qualifications for the Suffrage in the United States

Author(s): George H. Haynes

Literacy Tests, the Fourteenth Amendment, and District of

Columbia Voting: The Original Intent

Blackballing

Plainfield Historical Society

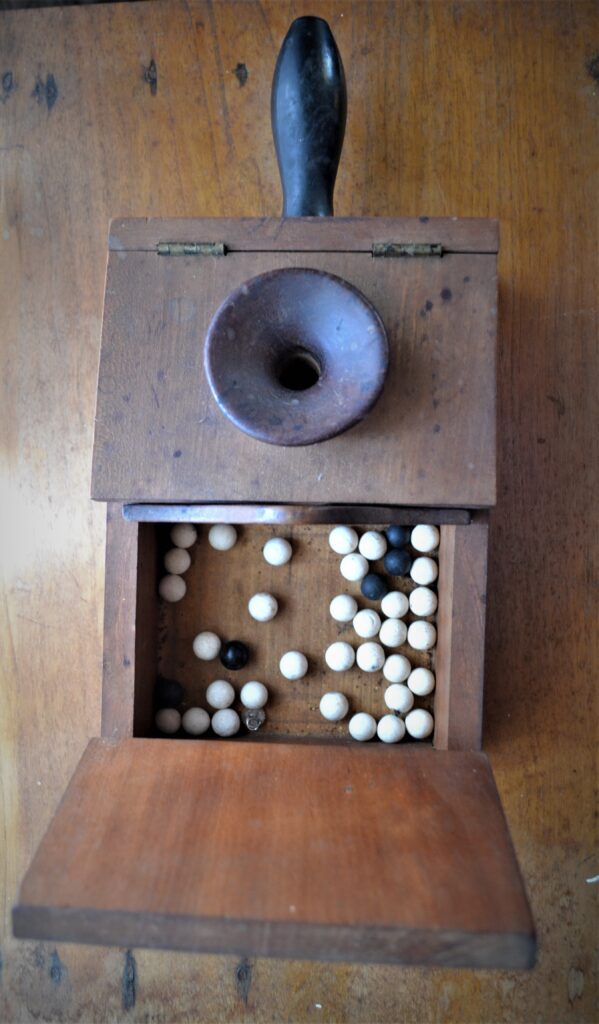

Blackballing was used as a traditional form of secret ballot, where a white ball or ballot constitutes a vote in support and a black ball signifies opposition. A large supply of black and white balls is provided for voters. Each voter audibly casts a single ball into the ballot box under cover of the box, so that observers can see who votes but not how they are voting. When all voting is complete, the box is opened and the balls displayed: all present can immediately see the result, without any means of knowing which members are objecting. Since the seventeenth century, these rules have commonly applied to elections to membership of many gentlemen’s clubs and similar institutions such as Masonic lodges and fraternities. This ballot box was used by members of the Plainfield Mountain Miller Relief Corp No. 158 Women’s Relief Corp.

“After the Civil War, as veteran’s organizations became popular, women followed suit. “All over the land ‘Ladies’ League,’ ‘Loyal Ladies,’ ‘Relief Corps,’ and other auxiliaries were established, all working in the interest of the soldiers, rendering valuable assistance to the Comrades in their work of aiding the unfortunates reverently, in true fraternity.” The Woman’s Relief Corps was one of these organizations. Much of the story of the Corps has been lost to history, along with its impact on patriotic education.” – excerpt from The Women’s Relief Corp: Missionaries of the Flag 1893 – 1918 by Stephanie Marie Schulze

As early as the 17th century in America, members of fraternal clubs often voted at their meetings without paper ballots. Many decisions had to be almost unanimous; just one “no” vote could defeat a project. So, they used a blackball box instead of paper ballots.

Each person was given a random number of black and white marbles. To vote no, a black marble was dropped in the box. The box had a board that covered the voter’s hand and marble so that no one could see the vote. Each marble made a noise when it was dropped, so only one marble could be used. When the box was opened, it was easy for everyone to see the number of black marbles and if the project, motion or request for membership had passed or failed. It was impossible to tell who had used a black marble.

The term “blackballed” is still in use today. The rules used are “Robert’s Rules of Order,” a guide to parliamentary procedure, but there are few times when only one vote, not a majority, is needed to make a decision. Robert’s Rules of Order is the standard set of rules first published in 1876 by Henry M. Robert to run orderly meetings with maximum fairness to all members.

A Short History of Voting Rights in America

While voting would seem fundamental in a democracy, voting rights in the U.S. have long been contentious. The Constitution makes no stipulations concerning who can vote. Instead, it is left to the states to decide, and they have often tried—with varying degrees of success—to limit voting.

States initially allowed only a select few to cast a ballot, enacting property, tax, religion, gender, and race requirements. In the first presidential election (1789), voters were almost all landowning white Protestant males. Movements to end various restrictions were subsequently mounted. In 1792 New Hampshire became the first state to remove its landowning requirement, though it took until 1856 for the last state (North Carolina) to drop property demands for white men. And while the Constitution decreed that no officeholder should be subjected to a religion test, various states continued to require one for voting until 1828, when Maryland allowed Jews to enter the ballot booth. By the 1860s white males largely enjoyed universal suffrage in the U.S.

But while voting rights were expanding for some areas of the population, states began enacting laws that barred women, African Americans, Native Americans, and many immigrants from casting ballots. The New Jersey constitution of 1776 gave voting rights to “all inhabitants,” and in the 1797 state legislative election, a number of women voted. However, the threat of a “government of petticoats” led the legislature to pass a law in 1807 that barred women from the polls. In 1821 New York amended its constitution to require black voters to own property worth an amount that effectively banned them from the ballot booth. Other examples of efforts to limit voting included the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), which prevented Chinese immigrants from becoming citizens and thereby blocked them from the polls.

After slavery ended, a campaign was launched to secure voting rights for African American men. This was seemingly fulfilled with the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, which guaranteed the right to vote to all men, regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” However, Southern states subsequently suppressed the black vote through intimidation and various other measures—such as poll taxes and literacy tests. The latter often required perfect scores and were frequently designed to be confusing; in one Louisiana test, the person was told to “Write every other word in this first line and print every third word in same line (original type smaller and first line ended at comma) but capitalize the fifth word that you write.” Such efforts proved so effective that by the early 20th century, nearly all African Americans had been disenfranchised in the South.

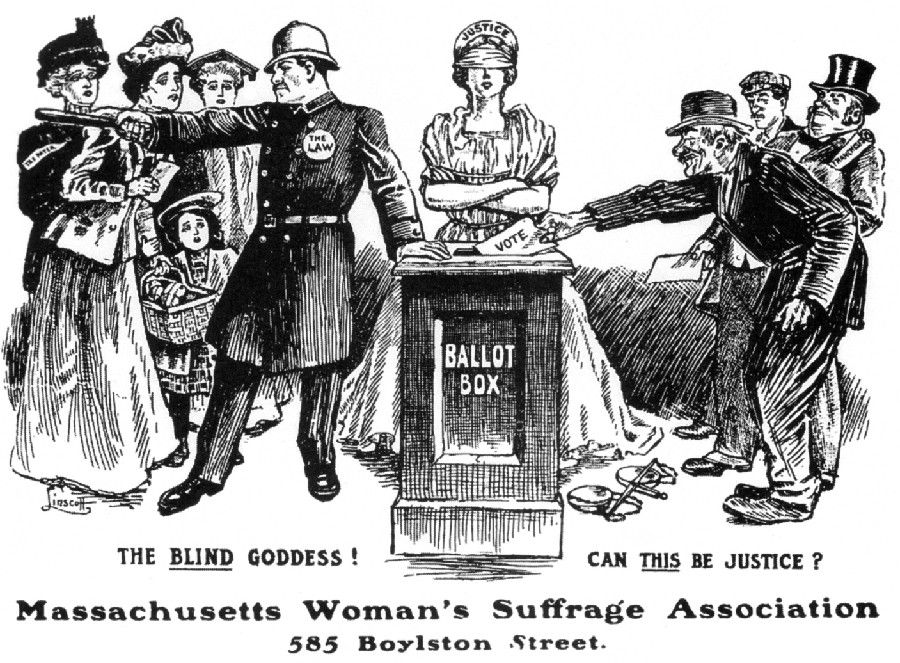

During this time, women were demanding the right to vote. The woman suffrage movement in the U.S. began in the early 19th century and was initially linked with antislavery efforts. Backed by formidable activists—notably Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone, and Susan B. Anthony—the movement slowly made progress. In 1890 Wyoming became the first state to adopt a constitution that granted women the right to vote, and by 1918 women had acquired equal suffrage with men in 15 states. However, it was realized that a constitutional amendment was needed, and in 1920 the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified when Tennessee approved the measure by one vote, becoming the 36th state to pass it; the victory was ensured only after a 24-year-old legislator changed his previous vote at the request of his mother, who told him “to be a good boy.”

In the ensuing decades, other groups—such as Native Americans (1957)—gained universal suffrage. For African Americans, however, their vote continued to be suppressed. By the mid-1960s fewer than 7 percent of blacks were registered to vote in Mississippi. With the civil rights movement, efforts were renewed to enforce the rights of African American voters. In 1964 the Twenty-fourth Amendment was adopted, prohibiting poll taxes in federal elections. The following year the Voting Rights Act was signed. The landmark legislation banned any effort to deny voting rights, such as literacy tests. In addition, Section 5 of the act provided for federal approval of proposed changes to voting laws or procedures in jurisdictions that had been deemed by a formula set forth in Section 4 to have practiced racial discrimination.

Sections 4 and 5 were repeatedly extended by Congress, but in 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court struck down Section 4, thus making Section 5 unenforceable. A number of states previously governed by Section 5 subsequently implemented various new measures, such as stricter voter ID requirements and limited early voting. Many of the changes had the proclaimed purpose of preventing voter fraud, though critics alleged that they were intended to suppress voting. Legal challenges resulted in a number of the laws being ruled unconstitutional. – excerpt from https://www.britannica.com/story/voting-in-the-usa

To read more about the history of voting rights in the United States click on the links below. And please, remember to vote on or before November 3, 2020.