Plants on Paper: Two Centuries of Collecting, Studying and the Art of Flora in Plainfield, Massachusetts

An Online Exhibit

Did you go botanizing as a child? Collect and press flowers in a book? Draw in a nature journal? Tend a pollinator garden? The fields and woods of Plainfield, Massachusetts have inspired residents, since its early settlement to the present, to collect and dry flowers and leaves, study botany, and make art and poetry inspired by the rich diversity of our flora.These activities have deep roots in history. The study of botany, in both Massachusetts and throughout the world, flourished in the late eighteenth century, when botanizing became a scientific pursuit, as well as an abiding hobby for many. And it continues today.

In the fall of 2018, the Plainfield Historical Society(PHS) serendipitously received a generous gift of a long lost herbarium, which eventually was the seed for us to bring history and botany together in an exhibition, “Plants on Paper: Two Centuries of Collecting, Studying and the Art of the Flora in Plainfield”, that was held at the Shaw Memorial Library throughout the summer of 2019.

Starting in the late 17th century with Plainfield’s first doctor, Dr. Jacob Porter, an avid botanist who was in close contact with the era’s leading scientists, Plainfield has a rich history of both science, agriculture, the arts, and industry, inspired by its rich botanical biodiversity. The PHS holds in its archives many examples of these histories. When we received Dr. Frances Shaw’s herbarium it was an opportunity for us to browse through our collections looking for these examples and bring them together to share and celebrate.

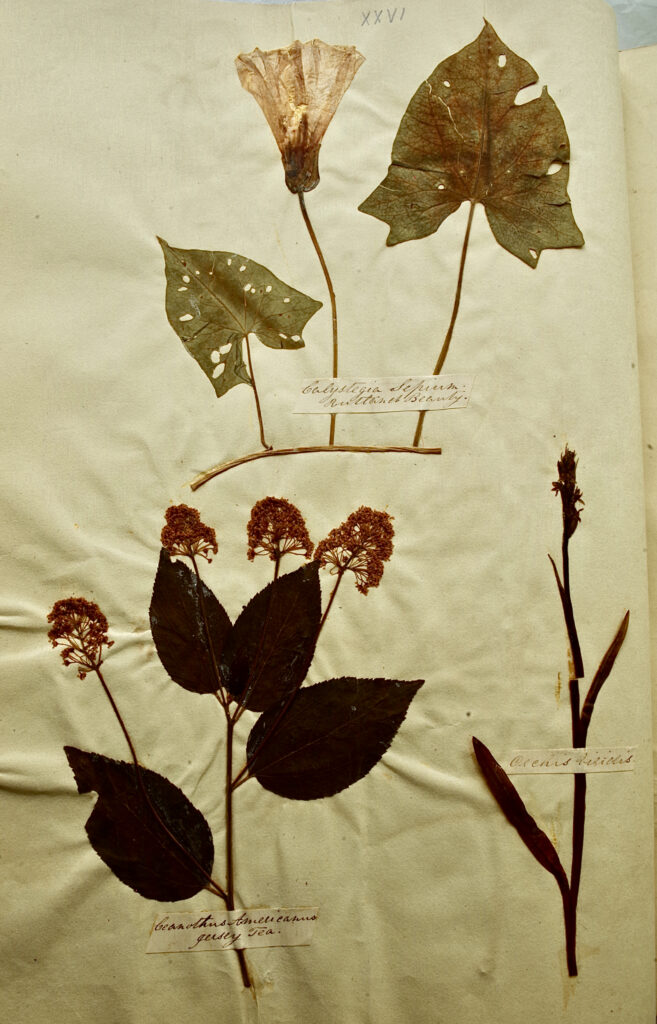

This donated ‘herbarium’, a collection of dried plants and flowers labeled with their scientific names, was created in 1854 by Samuel Francis Shaw, Dr. Jacob Porter’s neighbor, a graduate of Williams College, and a future doctor in the U.S. Navy. (Shaw grew up in the Shaw Hudson House). The herbarium was lost, saved fortuitously, and found its way to the PHS thanks to Robin Sauve of Longmeadow, MA. Ms. Sauve received the herbarium from Edward Anthony, a colleague from Philadelphia, at a convention they both attended. He knew that she lived in Massachusetts and might find someone interested in the herbarium, since it was from a student who attended Williams College. Mr. Anthony told her that his father had been a banker and that the herbarium had been left in a bank vault in Philadelphia and was never claimed. He had no personal connection to the Shaws or to Plainfield, just an interest in saving this unusual piece of history and finding a place that would appreciate its unique history, which it did! Ms. Sauve contacted us and then kindly donated the herbarium and the rest, you could say, is history.

During the late 18th century, when botany became a scientific pursuit and popular hobby, some of Plainfield’s most well-known citizens participated in this engaging endeavor. This exhibit includes Shaw’s 19-century herbarium as well as manuscripts, books, photographs and decorative materials held in the Plainfield Historical Society’s collections, all with a botanical theme. It also includes examples of 21st century botanical art, from the many talented citizen scientist/artist from the area. This website will take you on a virtual tour of that exhibit. As always, the blue highlighted text are links to other sites, with more informaton.

Exhibit One – Late 18th and Early 19th Century Botanists

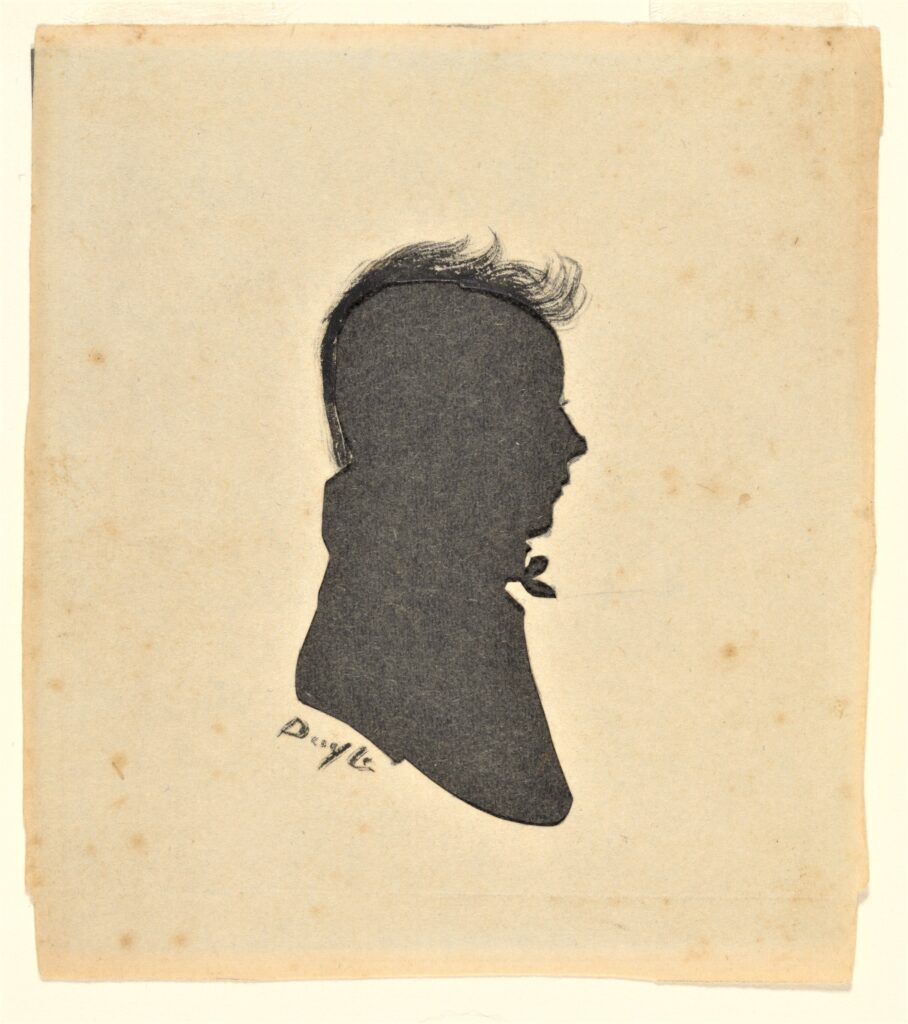

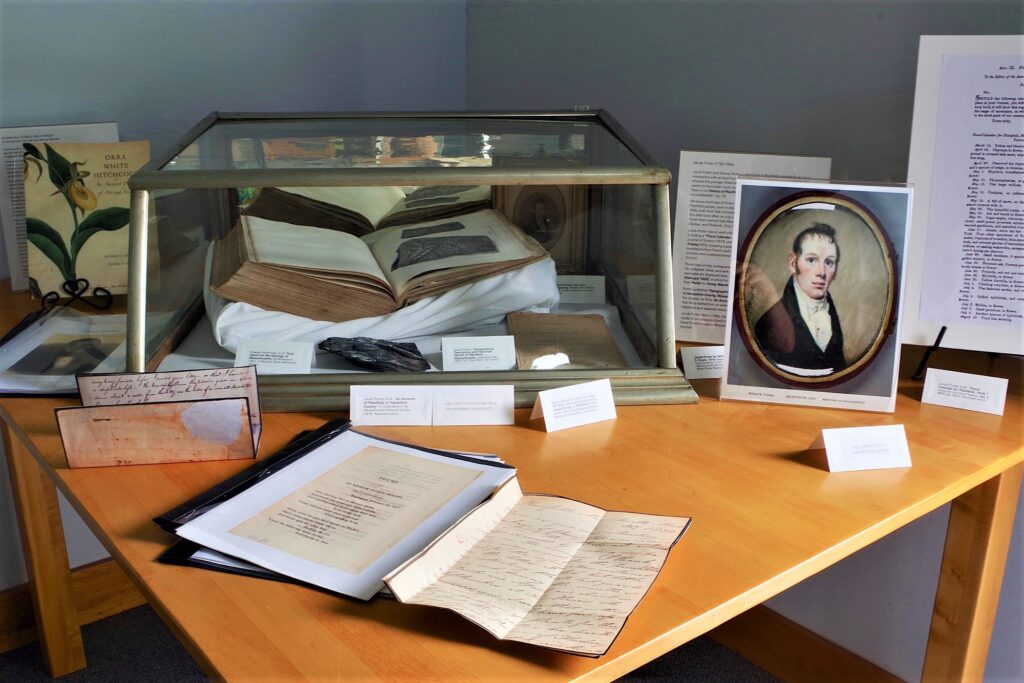

Included in this exhibit – 1. Copy of portrait of Jacob Porter by William M. S. Doyle, 1816. Watercolor on Ivory medallion 3 3/8 x 2 3/4 in. Yale University Art Gallery, Gift from Jacob Porter. 2. Jacob Porter Silhouette. Plainfield Historical Society Collections. 3. Jacob Porter, A.M. “An Account of Plainfield, in Hampshire County.” In Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, (1819) 4. Letter from Austin Abbott to John Torrey, Feb 13, 1822, discussing plants sent by Jacob Porter of Plainfield. Mertz Library, New York Botanical Garden. BHL Collections. 5. Silhouette of Jacob Porter. by William M S Doyle ca 1860. Plainfield Historical Society Collections. 6. Jacob Porter. Poems -Hartford [Conn.] : Printed by Peter B. Gleason, 1818. “To William Cullen Bryant, pp 5-8.” Google Books 7. Jacob Porter, A.M. “An Account of Plainfield, in Hampshire County.” In Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, (1819). 8. Final Report on the Geology of Massachusetts: Volume 1,Massachusetts. Geological Survey by Edward Hitchcock, 1840, J. H. Butler. Courtesy of the Shaw Memorial Library

Science was in the air at the end of the 18th and continued into the beginning of the 19th century. The establishment of a secular republic had created a civic as well as an economic commitment to seeking insights in nature based on observation.

Americans were interested in proving, once and for all, that the “new” world was neither a carbon copy of the old, nor a lesser version with smaller animals and plants. Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia (1785) contained a first salvo, and Americans avidly followed him in describing American nature in detail, and testify to its splendor.

The pursuit of Natural History, as it was known, encompassed the entire study of the world, ranging from geology to biology, sciences that had not established themselves yet as separate disciplines.

Within the larger whole, scientist like Amherst’s Edward Hitchcock (His 1840 Elementary Geology is in Exhibit One), Harvard’s Asa Gray (botanist, whose books are displayed in Exhibit Two) established professorships and schools, and had a great many correspondents and followers. Science illustrator and botanical artist Orra White Hitchcock, who married Hitchcock when he was still minister in Conway, was one of the few women who participated in the hot pursuit of greater knowledge of what the American world was hiding under her voluminous skirts.

Many of these men we might now call citizen-scientists — people who, on their own time and their own dime, systematically gathered the raw materials of life on earth that scientist sought to subject to systematic study: from fern leaves to skulls, fossils to the imprints of dinosaur feet, and from beetles and butterflies to descriptions of those strange scratches on large exposed rocks on the increasingly deforested hillsides of the Hampshire Hills. (Jacob Porter mentioned them as early as 1818).

These materials were part of the mountain of evidence built in the nineteenth century for scientific theories that span large swaths of time in the history of the earth and all that lives on it: geologic stratification, glaciation, evolution, and unfortunately also the pseudo-science of racial inequality. They were contested theories then, all of them in some ways as controversial today as they were then, although only few see the first three as unproven or the third as based in science.

It was often a gentlemen’s pursuit, although one wherein the gentlemen were very often professional practitioners of science, frequently physicians. These working men of science and learning in the Hilltowns were up to the moment in their interests and contacts.

Jacob Porter

Dr. Jacob Porter (1783-1846) and Dr. Samuel Shaw (1790-1870) were both physicians in Plainfield, neighbors at a busy intersection in the center of town. But whereas the younger Shaw became “the” doctor in Plainfield after 1824, Dr. Porter seems to have been much more interested in plants than in human beings. C.N. Dyer, in his History of Plainfield (1891) called his practice “very inconsiderable.” (p. 75)

We know much less of Porter than we do about Shaw. He was, like so many Plainfield people, born in Abington, Massachusetts. He received a B.A. in 1803 and an M.A. in 1806, both from Yale University. He married Betsey Mayhew on January 10, 1813. She died soon after, on July 3 of that same year, and is buried in Hilltop Cemetery. Porter then married Sally Reed in 1819, and they had three daughters, Juliet, Clarissa, and Elizabeth. Only Elizabeth survived him.

Jacob Porter was an avid collector of specimens, corresponded, published widely, including a “Floral Calendar of Plainfield” in the very first issue of the American Journal of Science (1819) and pursued other interests as well, including poetry (Poems, 1818, includes a poem to William Cullen Bryant), and even medical translations from French and Spanish. In addition, he drew attention, in papers, to minerals and scratched stones in the Hampshire hills, and wrote a paper on the Unicorn.

Porter had a lively correspondence with leading botanists, including Josiah Torrey. He collected, dried, and sent plants to include in the academic herbaria. Two examples are displayed here, one letter from Austin Abbott to Josiah Torrey (February 1822), in which he says he has received plants from Porter, and another from Porter to Torrey (March 1832) in which Porter mentions having sent plants.

Porter published the Topographical Description and Historical Sketch of Plainfield, in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, in 1834. Oddly enough, he did not include the chapter on flora, An Account of Plainfield, in Hampshire County …” (1819) that likely started him on writing about the (natural) history of Plainfield.

Jacob Porter died in 1846. He was, according to C.N. Dyer (75), buried in the shade of six tamaracks (larch trees) which he had planted in Hilltop cemetery. Sally Reed Porter moved to Wisconsin to live with her daughter Elizabeth Porter Mitchell.

Read an excerpt on Dr. Porter’s life in Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale College with Annals of the College History: June 1792-September 1805 By Franklin Bowditch Dexter

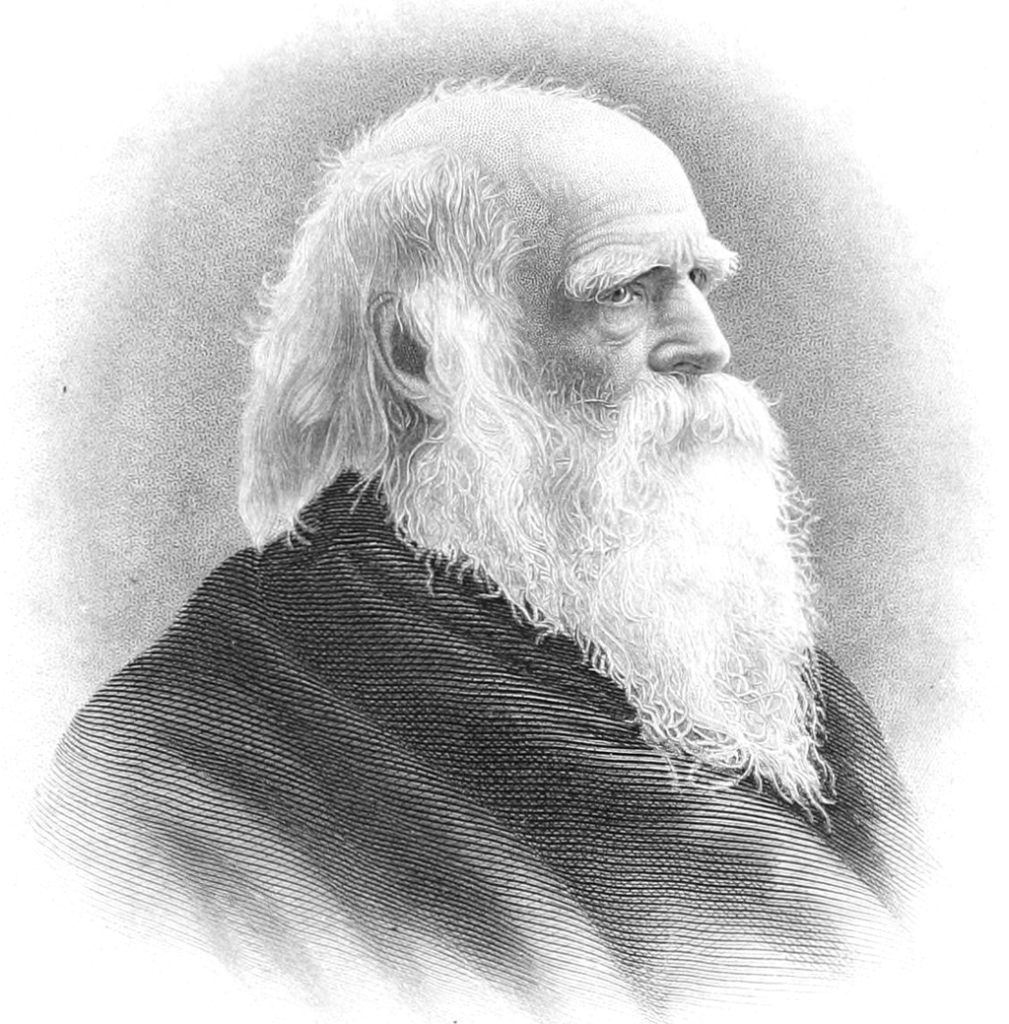

William Cullen Bryant

William Cullen Bryant, (1794–1878) one of the first popular poets of the 19th century, had many connections to Plainfield, with his homestead being a few miles just south of town. Bryant’s father was Dr. Peter Bryant, a close friend and mentor to Plainfield’s own Dr. Samuel Shaw. In fact, William’s sister, Sarah Snell Bryant Shaw was married to Dr. Samuel Shaw in 1821. She died of consumption at age 22, devastating the Shaw family and inspiring the beautiful poem by her distinguished brother, “The Death of the Flowers.”

William Cullen Bryant was not only a famous poet but for fifty years was also the editor and publisher of the New York Evening Post. His maternal grandfather Ebenezer Snell built this home in 1783, and Bryant spent his childhood and adolescence here. Bryant re-bought the property (which had been sold in 1835) in 1865 and made extensive alterations that essentially transformed it into a Victorian house. It was his summer home until his death.

It is obvious from his writings and poetry, that Mr. Bryant spent a good deal of time walking throughout Plainfield and surrounding towns, and was inspired by the flora and woodlands. He also shared his passion for botany with many Plainfield residents.

Learn more about William Cullen Bryant here

Correspondence of William Cullen Bryant 1809–1836

Poems of William Cullen Bryant

William Cullen Bryant and the Poetry of Natural Law

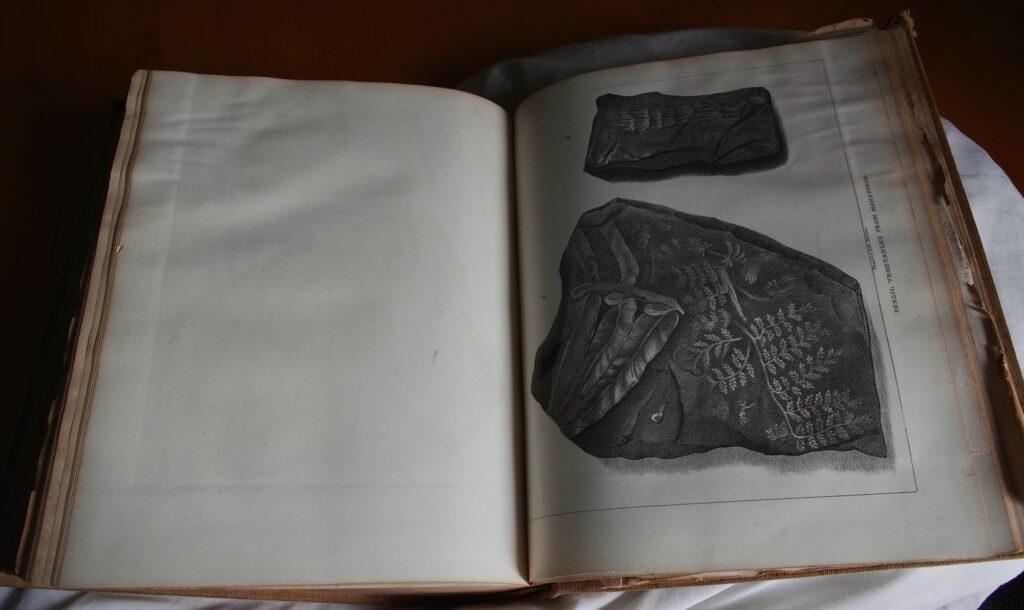

Edward Hitchcock and Orra White Hitchcock

Orra White Hitchcock ((March 8, 1796 – May 26, 1863) and her husband Edward, (May 24, 1793 – February 27, 1864) Edward Hitchcock was an American geologist and the third President of Amherst College. He and his wife, Orra White Hitchcock, collected and dried a variety of grasses and wildflowers from our region, influencing many of the botanists of the time, including Plainfield’s own Jacob Porter and members of the Shaw family. From 1817-1821, Orra created 63 watercolor images of their collection and compiled them into a book called Herbarium parvum pictum.

It is very likely that there was a sharing of ideas and notes on the botany of Plainfield between Edward and Dr. Porter, as well as the geology of the region, as Dr. Porter is mentioned several times in Hitchcock’s letters and notes. There also is a 1st edition copy of Hitchcock’s Geology of the Connecticut Valley (1823) in the Shaw Memorial Library that may very well have come to Plainfield from Hitchcock himself.

To learn more about the Hitchcocks and to see Orra’s drawings visit the following:

Edward and Orra White Hitchcock Papers, 1805-1910 1811-1864 Amherst College

Amherst College Collection of Orra White Hitchcock drawings

Amherst College Collection of Edward and Orra White Hitchcock papers

View more of Orra White Hitchcock’s Drawings

Charting the Divine Plan: The Art of Orra White Hitchcock (1796–1863 June 12, 2018–October 14, 2018 from the American Folk Art Museum Collection

Massachusetts. Geological Survey by Edward Hitchcock Jan 1841

As part of this exhibit we were pleased to have a presentation on Orra White Hitchcock by Reba- Jean Shaw Pichette, curator of the Shelburne Historical Society. Ms. Pichette brought to life the little-known work of one of the Connecticut River Valley’s earliest female artists and a leading scientific illustrator of her time, Orra White Hitchcock. Shaw-Pichette, a museum educator at the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, has worked in this field for more than 20 years. Ms. Shaw-Pinchette took on the persona of Orra White Hitchcock and invite us all to step into her life. She also offered guests a chance to try their hand at botanical illustrations.

Exhibit Two – Mid-19th and Early 20th Century Botanists

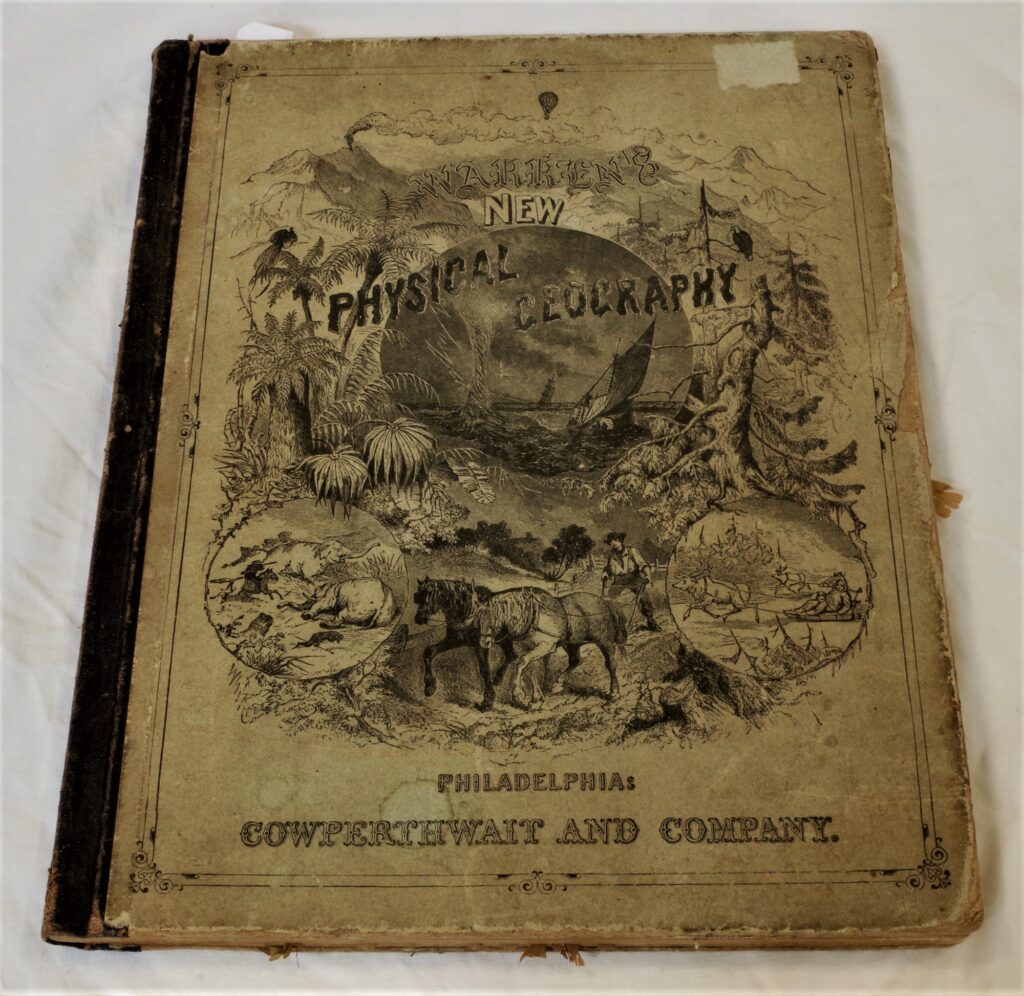

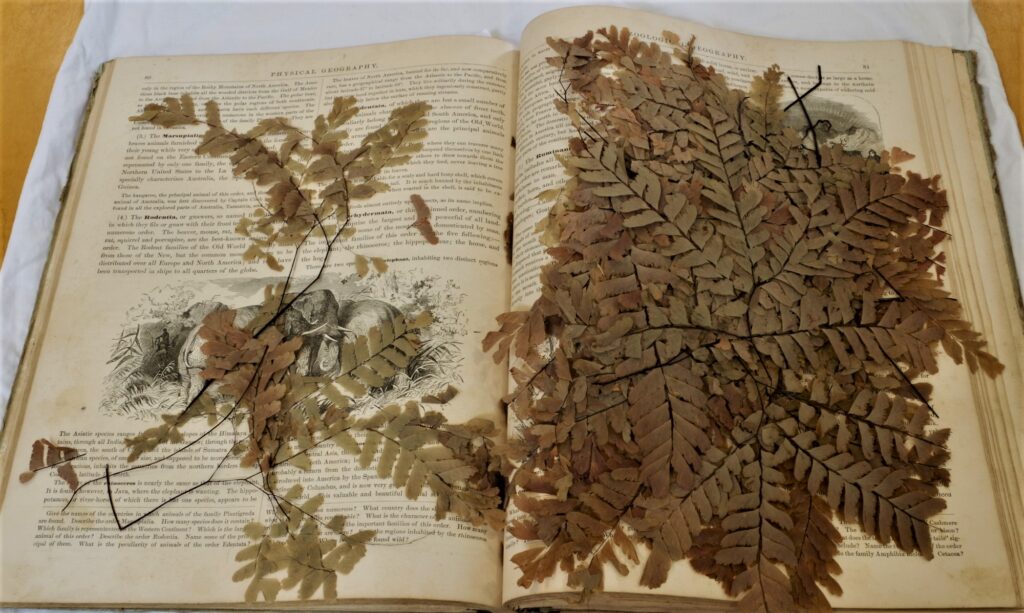

Dr. Samuel Francis Shaw’s Herbarium

Created in 1854 by Plainfield native Samuel Francis Shaw, the herbarium is a collection of dried plants and flowers labeled with their scientific names. (To find out more about herbariums or to start your own click here,) Samuel Francis Shaw (1833-1884) was the son of Dr. Samuel Shaw, who for over a half century was a practicing physician in Plainfield. Samuel Francis Shaw attended Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts and graduated with the class of 1855. Students from Rev. Moses Hallock’s classical school in Plainfield had attended Williams College since its founding in 1793. After graduation Samuel Francis spent four years in Plainfield studying medicine and natural history. In 1859 he went to New York City to continue his medical studies at the College of Physicians and Surgeons from which he was graduated in 1862. He joined the U.S. Navy and served as a surgeon on many ships that took him to the West Indies, Japan, China, and the East Indies. After serving almost 20 years in the Navy he settled in Philadelphia where he continued his profession. It seems logical that this is how the herbarium ended up in Philadelphia.

In the History of the Town of Plainfield, Hampshire County, Mass: From Its Settlement to 1891, Including a Genealogical History of Twenty Three of the Original Settlers and Their Descendants, with Anecdotes and Sketches, Charles N. Dyer writes – “Samuel Francis Shaw, son of Dr. Samuel, was born at Plainfield, Sept. 7, 1833. He was fitted for college at the Northampton Collegiate Institute. Entered Williams College in 1852, and was graduated in 1855. After graduation he remained at home four years, studying medicine with his father and making collections of native plants and birds. He studied medicine at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, graduating in 1802. A few months later he entered the navy as assistant surgeon. During his service of nineteen years he made many long voyages, visiting the West Indies, the Azores, Peru, Sitka, China, Japan and Siberia. He married Oct. 27, 1877, Adelaide Roberts, daughter of Edward Roberts, Esq., of Philadelphia, and sister of the well-known artist, Howard Roberts, whose statue of Fulton is in the Capitol at Washington. After spending a year with his wife in traveling through Europe, he resigned his surgeon’s commission and settled in Philadelphia. He died at his home 1909 Walnut St., Dec. 7, 1884. Dr. Shaw was a man of commanding presence. His tall and well proportioned figure, over six feet in height, together with a handsome face which was lighted up by a pair of blue eyes of unusual softness and beauty, attracted universal attention. While his great dignity of character inspired respect, his unselfishness won the affection of all who knew him.“

To see a gallery of the entire herbarium click here.

To find out more about Dr. Frances Shaw click here.

Williams College Yearbook 1885 with mention of Dr. Frances Shaw

To learn the value of herbariums throughout the ages and their relevance today click here.

Click here to watch a video on the Shaw Hudson House by William Hosley

Connections Between Plainfield and Fellow Botanists of the 19th Century

While searching through the Plainfield Historical Society’s archives we were delighted to find many connections between Plainfield and some of the top botanists of the 18th and 19th centuries, which inspired us to put together this exhibit.

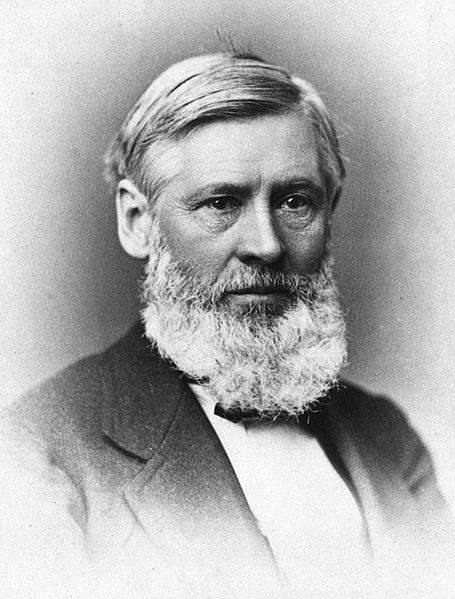

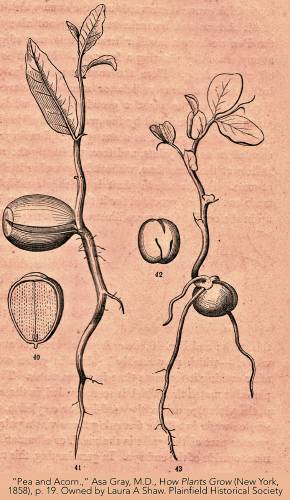

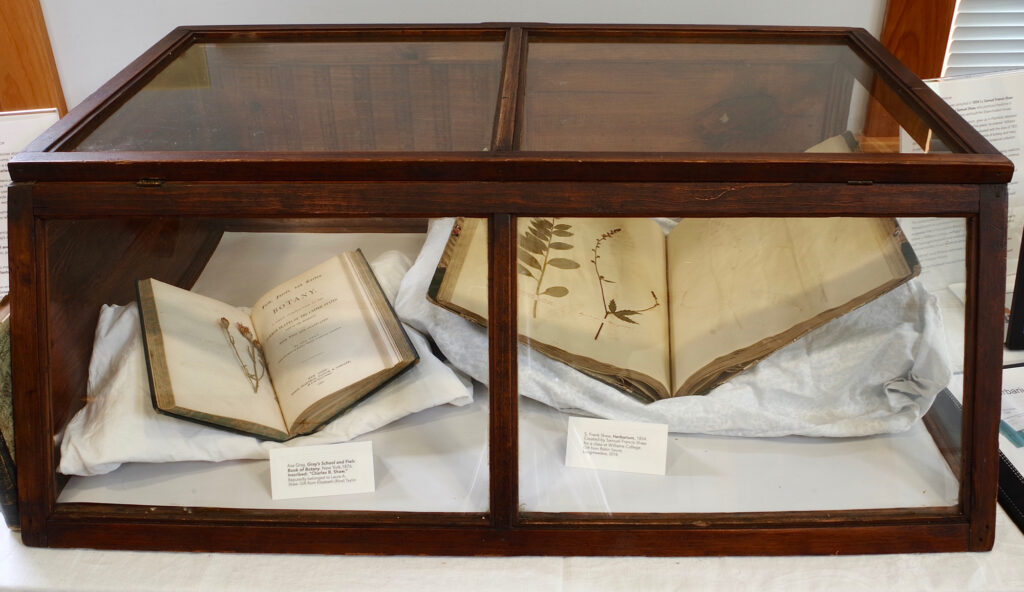

Asa Gray

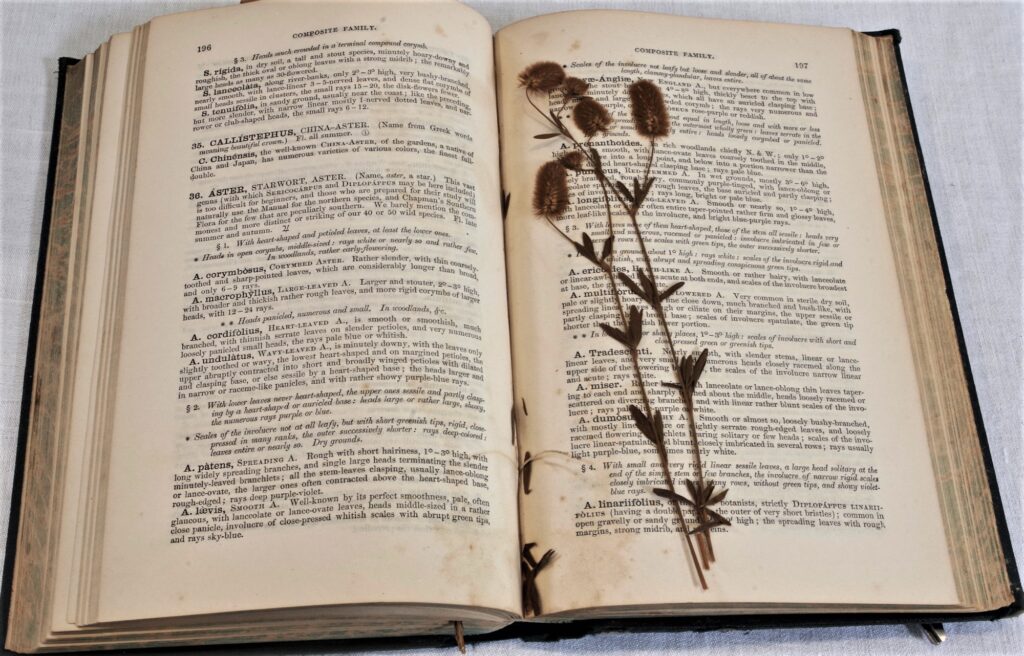

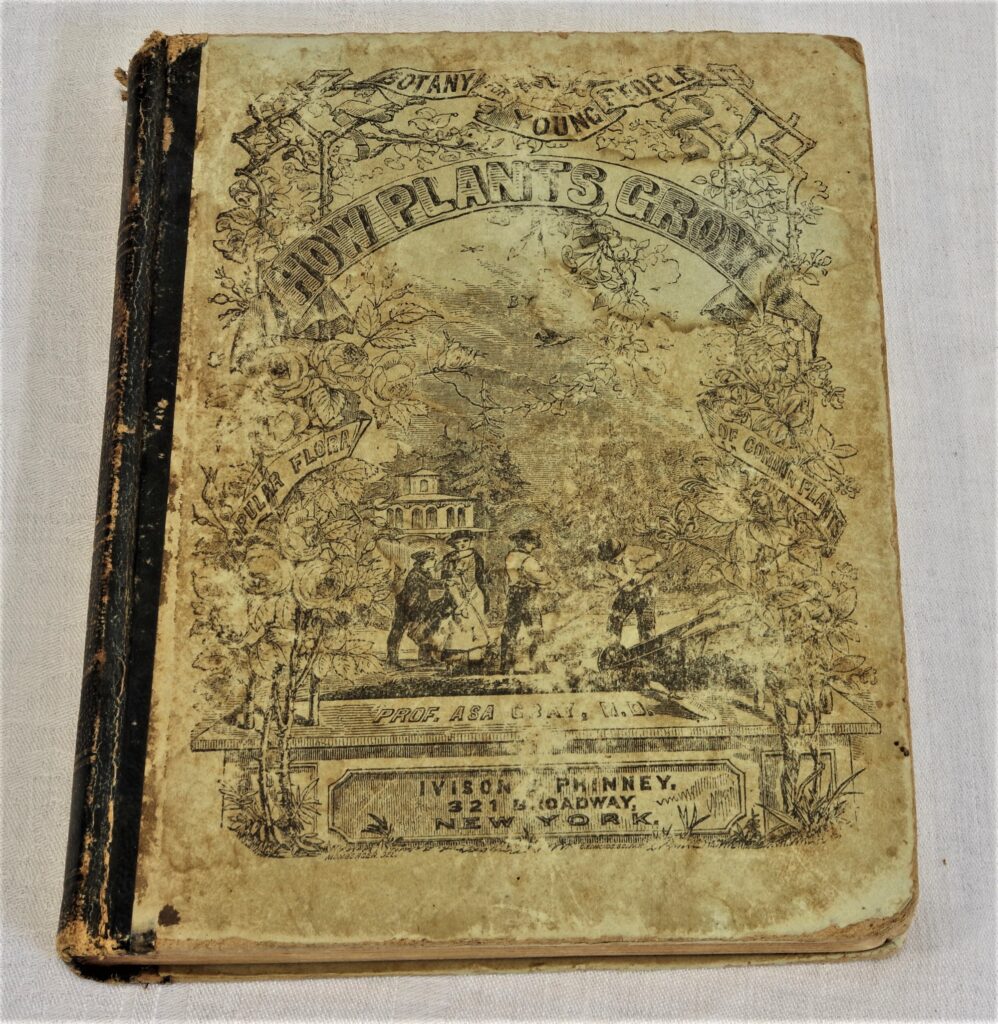

Asa Gray ( 1810- 1888) may not be a household name for most people, but the “Father of American Botany” was a remarkable man. Gray was born in 1810. Just as Dr. Jabob Porter had, he began his career as a medical doctor but found that his true passion was for plants. He studied botany under John Torrey and became the first permanent professor at the new University of Michigan in 1838; his position was the first at any U.S. institution to be exclusively devoted to botany. Gray traveled and studied extensively throughout North America and Europe and met with many prestigious botanists and naturalists, including Sir William Hooker, Augustin Pyrame de Candolle and his son Alphonse, John Muir, and Charles Darwin.

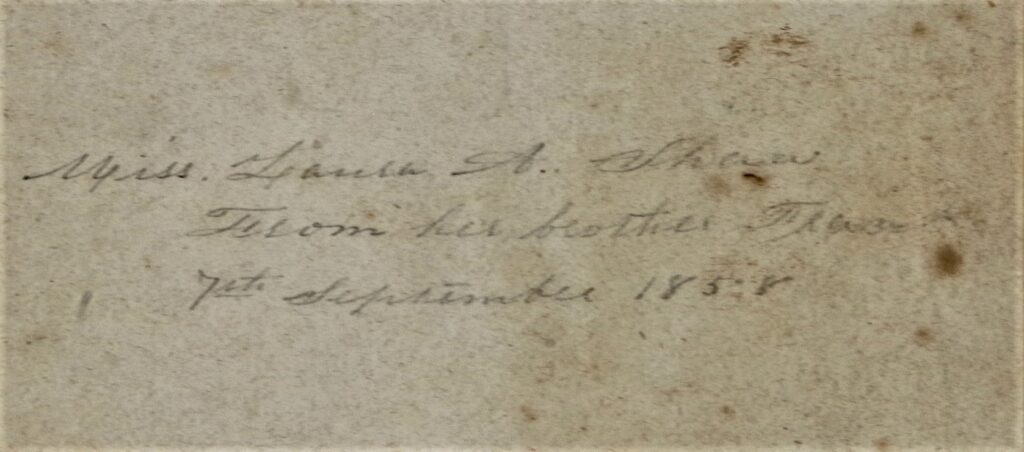

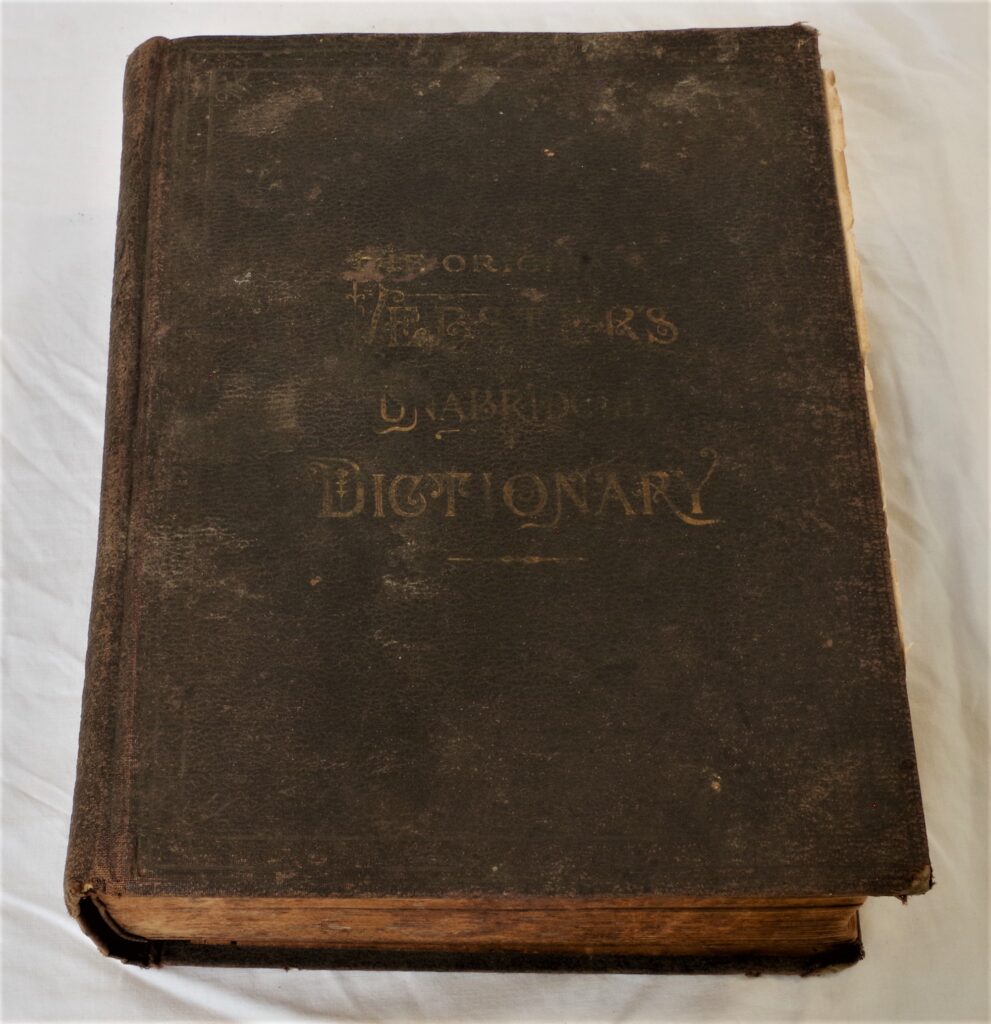

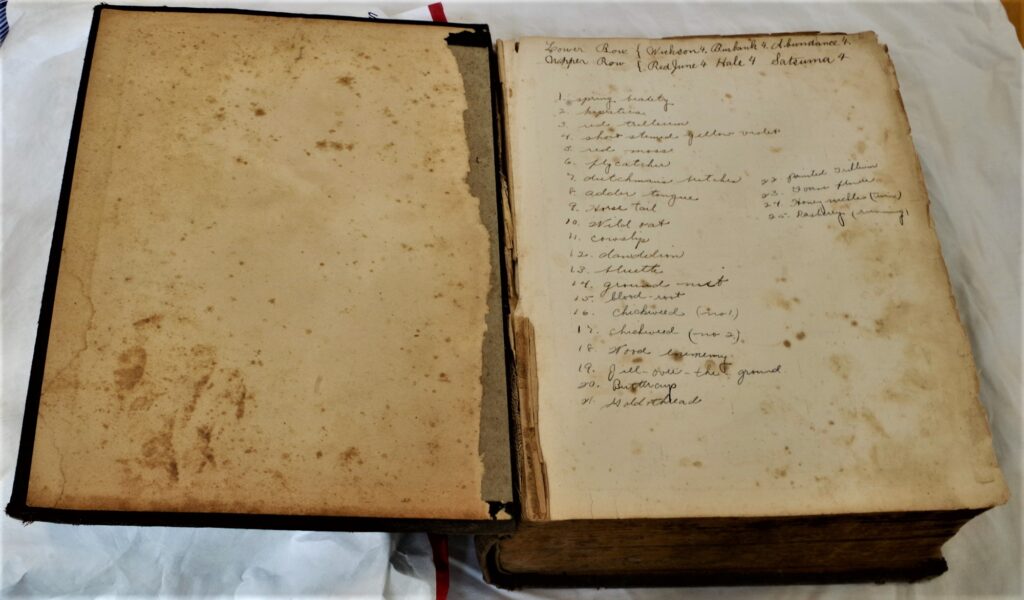

The Plainfield Historical Society has a copy of Asa Gray’s How Plants Grow; New York, Ivison and Phinney, 1858. Inscribed: “September 7, 1858, Miss Laura A. Hudson, from her brother Frank.” Donated by Elizabeth [Rice] Taylor as well as Gray’s School and Field Book of Botany. Inscribed: “Charles B. Shaw.” Reputedly to have belonged to Laura A. Shaw.

How Charles Darwin Seduced Asa Gray an interesting read about two of the greatest botanists of the times.

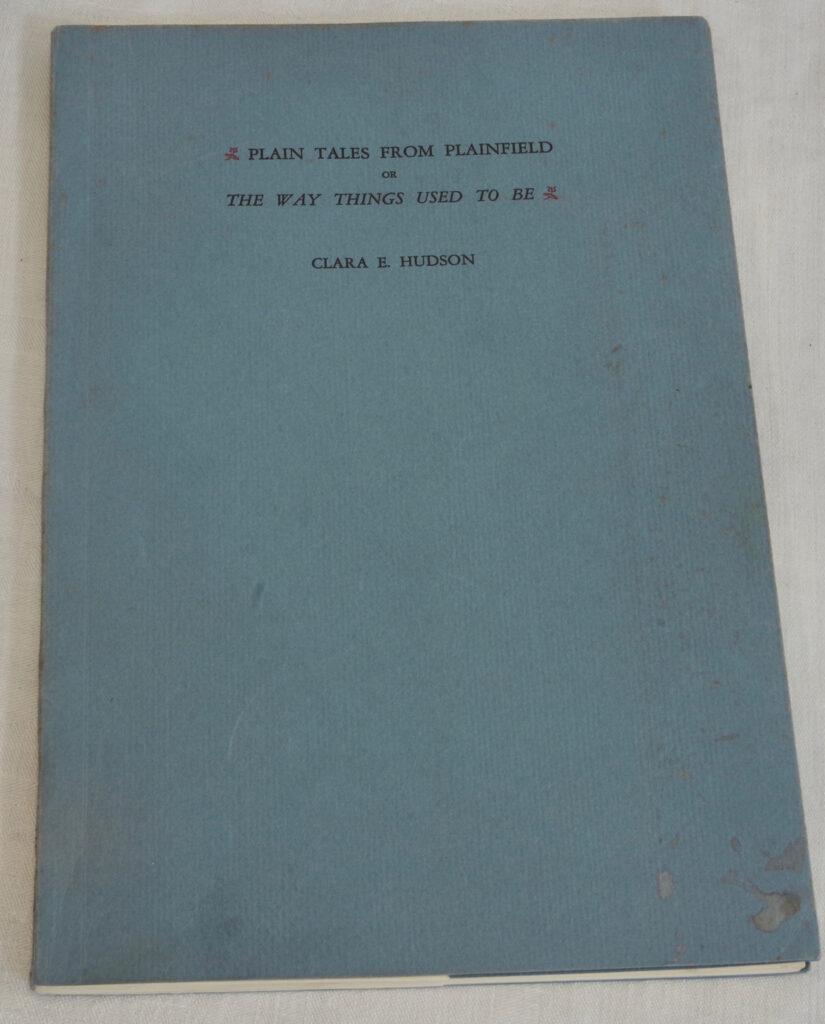

Clara Elizabeth Hudson

Clara Elizabeth Hudson(1880 – 1963) Miss Hudson’s stories of summering in Plainfield show the family’s shared interest in plants, but also what role women and girls played in that pursuit: “My uncle [Charles Lyman Shaw] often brought home interesting botanical specimens which my mother and I sometimes identified with the aid of Gray’s manual.” Charles. Lyman Shaw’s manual, Gray’s School and Field Book of Botany (1876) still contains flowers, dried between its pages, perhaps by Hudson and her mother.

Clara Elizabeth Hudson published her stories of Plainfield and of her family as she was growing up in a small volume, Plain Tales from Plainfield, or The Way Things Used to Be (1962). In a section entitled “Botany, Geology, and Biology,” she described her uncle, Charles Lyman Shaw:

“With his metal vasculum [botany box] to hold botanical specimens slung over his shoulder, he took many long tramps,… [in] the Hampshire Hills near Plainfield. One friend, a Springfield doctor who used to visit him, liked these walks also. The doctor was short and fat; my uncle rather tall and thin. The combination reminded one of a period and an exclamation point.”

Hudson’s words not only testify to her sense of humor, a prized trait in the family, but to the family’s shared interest in plants.

“My uncle often brought home interesting botanical specimens which my mother and I sometimes identified with the aid of Gray’s manual.”

In addition to the Field Guide, Hudson also mentioned Gray’s earlier and groundbreaking 1858 botany text book, How Plants Grow likely the very same volume currently in our collection.:

“I remember that one book by Gray was entitled How Plants Grow. As A child, I read the title as How Plants Grow Gray. I didn’t know of any plants that grew gray, except lichens and I thought the title most peculiar.”

The family did not hang on to these volumes, which may have been displaced by more modern field guides, and we believe they ended up with Elizabeth Thatcher Rice of Plainfield and were eventually donated to the Plainfield Historical Society by her daughter, Elizabeth [Rice] Taylor.

Clara’s father was Dr. Erasmus Darwin Jr. (1843-1887 ) He was the son of orthopedic surgeon and abolitionist Erasmus Darwin Hudson. He graduated from the College of the City of New York in 1864, and at the New York College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1867. He was house surgeon of Bellevue Hospital in 1867, and held the office of health inspector of New York City in 1869. In 1870 he was attending physician to the class for diseases of the eye of the outdoor department of Bellevue hospital, and from 1870 until 1872 was attending physician at the Northwestern Dispensary. From 1870 until his death, he was attending physician to Trinity Chapel parish and Trinity Home. He was professor of principles and practice of medicine in the Woman’s Medical College of New York infirmary from 1872 until 1882, and professor of general medicine and physical diagnosis in the New York Polyclinic from 1882 until his death.

While Ms. Hudson never married she summered in Plainfield often and wrote about her many fond memories of the town and its environs. She was active in town affairs as indicated in a short biography in Woman’s Who’s who of America: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporary Women of the United States and Canada, 1914-1915, which states that she was active in both the Hilltop Camp Fire Girls of America in Plainfield and the Plainfield Christian Endeavor Society. In many of her writings, Ms. Hudson mentions the flora of her beloved Plainfield.

The Romances of a Country Doctor A Paper Read by The Country Doctor’s Grand-Daughter Miss Clara Hudson at the Annual Meeting of the Northampton Historical Society at The Unitarian Church, Northampton, MA, Tuesday Afternoon, October 7, 1947

To learn more about the Hudson family, Hudson Papers. University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Exhibit Three – Early 20th and 21st Century Botanists, Artists and Decorative Arts

The Rise of Consumer Decorative Arts

As exotic flora and fauna from across the world made their way to Europe and America, personal study of botany began to grow in popularity. This interest coincided with increasing affordability of materials such as glass and steel that supported construction of a growing number of conservatories in private homes, designed to showcase collections of tropical plants, ferns, and other botanical specimens. Artists continued to produce botanical illustrations throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, but the Victorian period witnessed a shift towards the more decorative arts. This, along with more readily available exports from the Far East lead to an explosion of demand for scientific inspired home decoration, particularly botanical decorations. In the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, vases, dinnerware, textiles, and fountains became the rage and were available to the masses. Tole painting, a form of folk art of decorative painting on tin and wooden utensils, objects and furniture became popular during this period. Many of us have been handed down a dinnerware set or piece of ceramic from this period, the PHS included. Thus, the mid-19th to early 20th century became the golden period of botanical decorative ware and was embraced by both the Art Nouveau movement and what would later be called the Arts and Crafts Movement.

The Arts Story: The History of the Arts and Crafts Movement

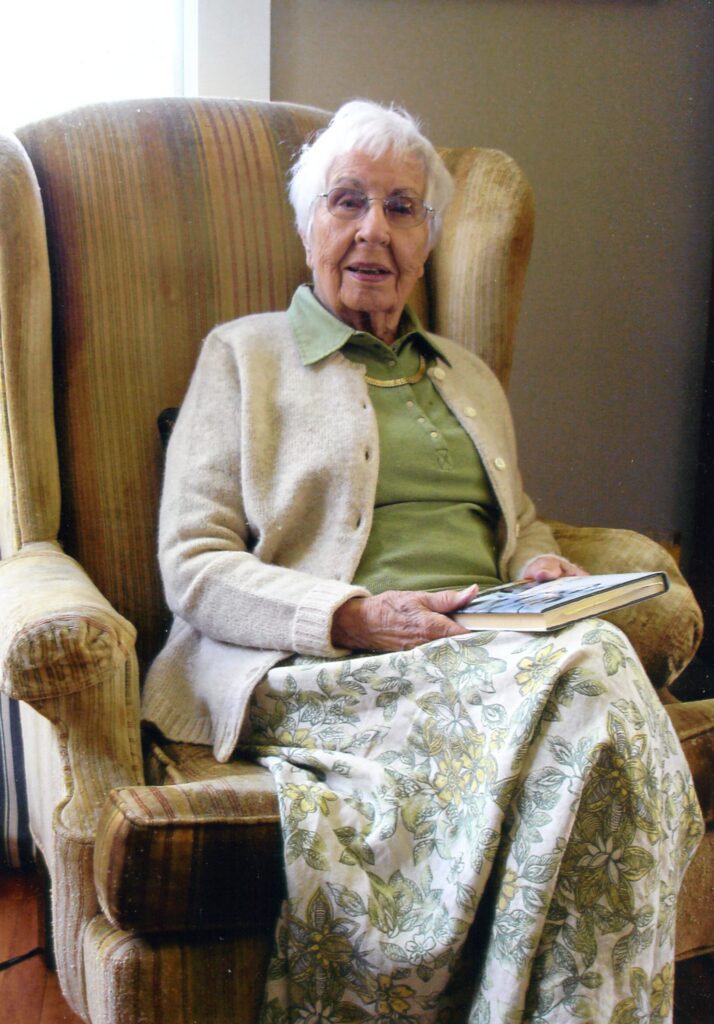

Kay Dilger Metcalfe and Tole Painting

Mary Kay Metcalfe (1912 – 2018) Born in Noblesville, Indiana, on November 15, 1912, she was christened Mary Kathryn Dilger, but decided during high school that she wanted to be known as Kay, a name that stuck.

Kay has always been a deep thinker and a questioner. At a young age, she developed an idea that has lasted from childhood to old age: “The idea that I’m responsible for myself.” When Kay was about 12 years old, she got scarlet fever. Her family brought her on a camping trip to Windsor Pond to recover. Not only did she regain her health, but she, and the rest of the family, fell in love with the area. In the mid-1930s they built a cabin on the Pond, and in 1946 they bought the farmhouse in Plainfield, where Kay remained until her death in 2018 at the age of 105.

Since childhood, Kay has loved painting and drawing. Her interest in the arts—as well as her agency in taking responsibility for her own life—helped her to achieve her dream of “a season in Paris” when she was about 20 years old. This life-changing experience was part of a 3-year program in art and architecture at the Parsons School of Design in New York City.

Once her children left for college, Kay was eager to use her artistic talents in the world outside her home. She took a job designing visual displays for the Yonkers, New York, Public Library, a job that lasted until her retirement 17 years later.

In retirement, Kay took up the early New England craft of tole painting on household objects. She became well known in Plainfield and beyond as a master of this craft, which tapped into her love of history as well as her artistic talent. (Courtesy of Rebecca Mlynarczk from Coming of Age in Plainfield: Women’s Stories of Successful Aging)

Tole painting is the folk art of decorative painting on tin and wooden utensils, objects and furniture. Typical metal objects include utensils, coffee pots, and similar household items. Wooden objects include tables, chairs, and chests, including hope chests, toy boxes and jewelry boxes. Below are a few samples of Kay’s tole work.

To learn more about tole painting or to give it a try yourself click here.

Pressed and Dried Flowers

During the Victorian Era it became a very popular hobby with ladies of every social class to press or dry flowers to display throughout the home. Requiring very little specialized supplies or expertise, collecting, pressing, and drying flowers became the rage. “There were many reasons that someone might collect flowers during this time, from the sentimental, preserving a flower given as a gift from a loved one, to the scientific (keeping a botanical scrapbook to aid in identifying native blooms). Regardless of the reason, the practice of pressing flowers was highly regarded as a creative pastime, and many would take pains to ensure that their work was beautifully displayed. Flowers of the time were often found framed behind glass in elaborate arrangements, sometimes with pieces of ribbon to complement the blooms, or meticulously organized in scrapbooks with their taxonomical description written next to them.” (Pressed Flowers by S. Brosious)

As members of the PHS sort through the vast collections of books, including many family Bibles, we have come across examples of pressed flowers. Below are two examples.

Skeletal Leaves

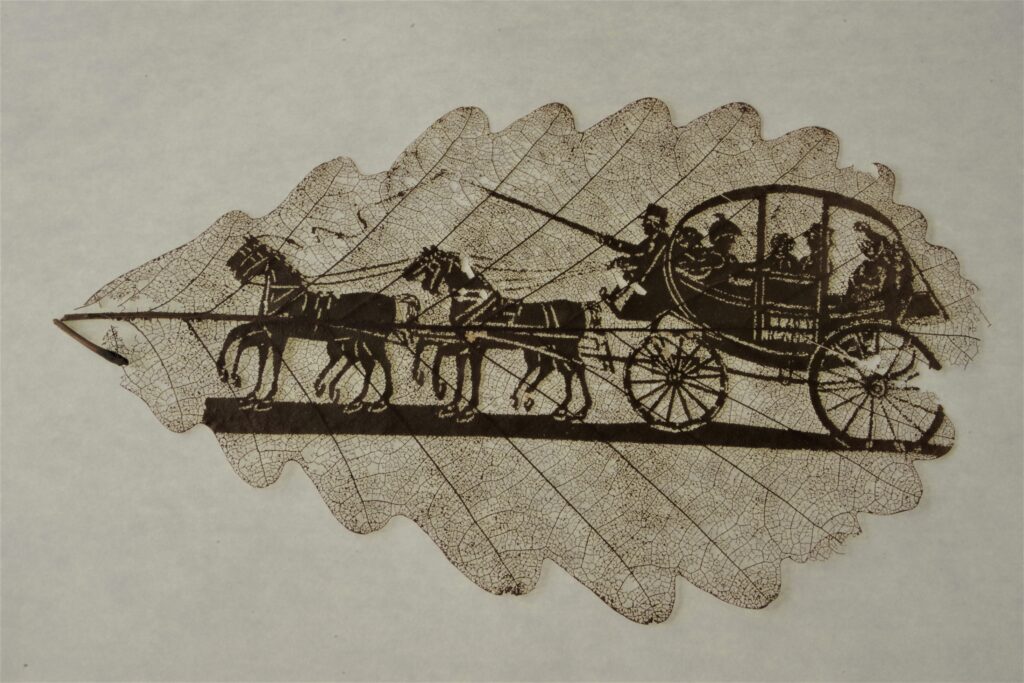

Sitting in a linen draw in the upstairs of the Shaw Hudson House, for no one knows how long, was a small blue box, possibly a hosiery box, that when opened, held a delightful surprise. Wrapped in old tissue paper were a dozen, delicate leaves, all skeletonized with intricate designs. These leaves were a mystery to us and so we put our researchers’ hats on to investigate. We reached out to museums far and wide, but could find little information on them. The book “The Phantom Bouquet: A Popular Treatise on the Art of Skeletonizing Leaves” by Edward Parrish, published in 1863, is the best source of information on these leaves. Mr. Parrish writes, “Some years ago the writer was attracted by a beautiful vase of prepared leaves and seed vessels displaying the delicate veining of these plant structures deprived of their grosser particles and of such brilliant whiteness as to suggest the idea of perfectly bleached artificial lace work or exquisite carvings in ivory This elegant parlor ornament was brought by returning travellers as a novel and choice trophy of their transatlantic wanderings none could be procured in America and no one to whom the perplexed admirer could appeal was able to give a clue to the process by which such surprising beauty and perfection of detail could be evolved from structures which generally rank among the least admired expansions of the tissue of the plant.”

It is known that members of the Shaw/Hudson family traveled throughout the world and one can only assume that one of them brought back these leaves from their travels.

When we consulted Michael Sage aka The Real Leaf Man, an expert in phantom leaves, he wrote us: “These were made during the Victorian period. I have seen a few others that are similar and actually have the horse drawn carriage piece in my collection. I do not know exactly how these were made but suspect they degraded the leaves with a mild caustic (soda ash) and were able to do this with a template covering portions of the leaf. These leaves were not properly preserved so great care should be taken in moving and handling them. They are quite rare lovely!“

We have taken Mr. Sage’s advice, carefully photographed each leave, wrapped them in archival paper and returned them to the draw in which they have resided for who knows how long, in the hopes that one day we will discover the story behind these leaves.

To see a gallery of these beautiful botanical wonders click here.

To learn more about women and the decorative arts click here.

Poetry

Western Massachusetts is known for its famous poets and writers, many inspired by its beautiful flora and fauna. Writers such as Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Herman Melville, Emily Dickenson, and of course, William Cullen Bryant, all contributed to the botanical arts through their writings. Here in Plainfield, we too, have our poets and writers, perhaps not as well known, but equally as enjoyable in our eyes! Here are just a few that we have in our collections.

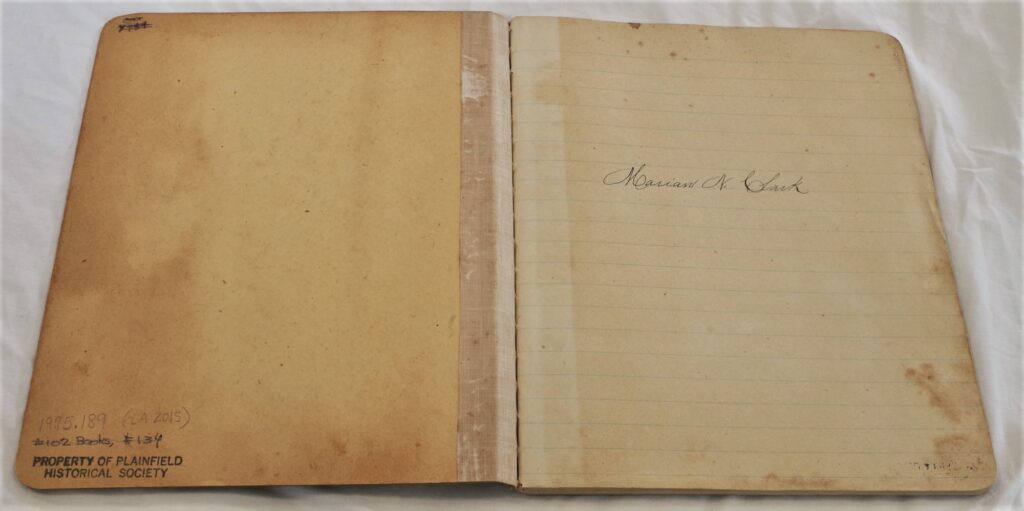

Marion Nancy Clark

Marian Nancy Clark (1870-1961) was born June 2, 1870 in Plainfield, Massachusetts to Seth William Clark and Nancy Jones Clark. The Clarks lived with Seth’s parents, Chester and Minerva, on the family farm located on South Street, from the late 1850’s well into the 1880’s. Never marrying, Marian lived with her parents until their passing. After 1910 Marian moved in with her older married sister, Ella Clark Tirrell and husband Arthur, who lived in South Amherst, Massachusetts.

Reading Marian’s poems offers a thought that Marian took much comfort from nature, and one can only imagine how beautiful her flower beds were. Records only show brief employment as a housekeeper at a private home, so Marian may have been allowed many hours to write poetry. By the 1940’s Marian 69, Alice 71, and widowed Ella 83, were living together in Amherst, Massachusetts. On August 17, 1961 Marian passed away and was brought back to Plainfield to be buried at Plainfield’s Hill Top Cemetery.

To read some of Marion Clark’s poetry on the botanical wonders of Plainfield, click here.

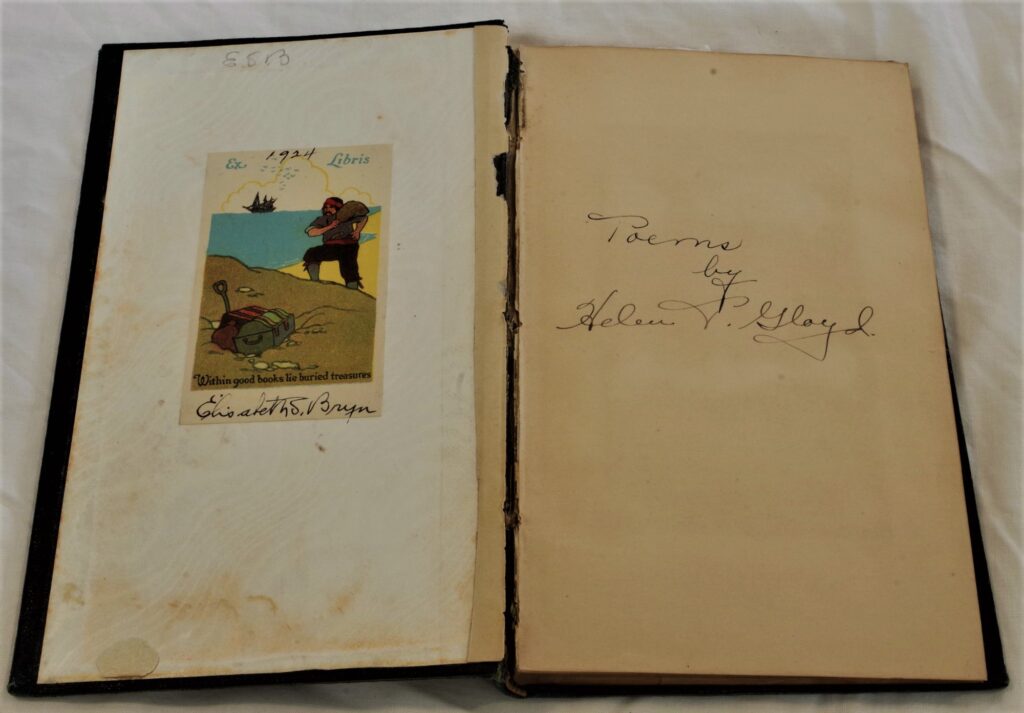

Helen Parent Hoornbeck Gloyd

Helen Parent Hoornbeck Gloyd was born June 22, 1894 in Chicago, Illinois to William P. Hoornbeck and Harriet Rand Goodwin Hoornbeck. After her father died, the family moved to Everett, Massachusetts by 1910 to live with Harriet’s father, George Goodwin. On December 22, 1916, Helen married Ralph Edwin Gloyd and according to the census, spent the next thirty years, or more, living in Plainfield, on their Grant Street farm.

In between the rhythm of farm chores and raising Ralph Jr., Dorothy Helen, Robert Henry and Virginia E., Helen set aside time to write her poems. The poems were published, and collected in a volume by Elizabeth S. Bryn and are in the Plainfield Historical Society’s collections. During her later years, Helen lived in Los Angeles, California, although, when she passed on February 22, 1984, she chose to be buried in Plainfield’s Hilltop Cemetery.

To read some of Helen Gloyd’s poems on our local flora click here.

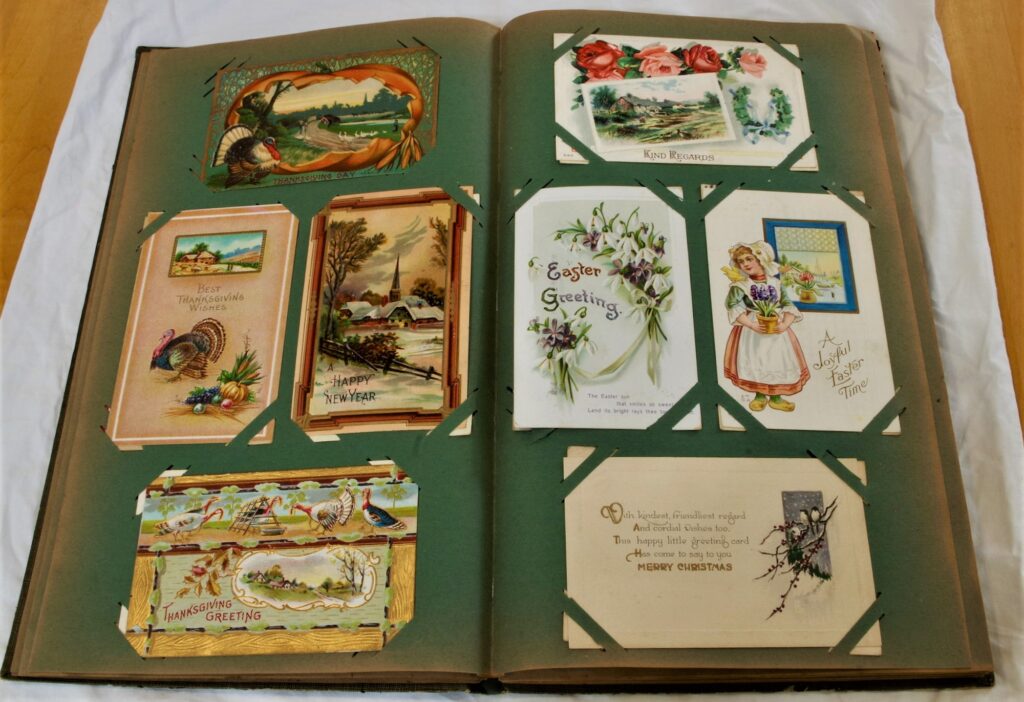

Post Card Collections

Spanning from approximately 1905 to 1915 in the United States, the golden age of postcards stemmed from a combination of social, economic, and governmental factors. Demand for postcards increased, government restrictions on production loosened, and technological advances (in photography, printing, and mass production) made the boom possible. In addition, the expansion of Rural Free Delivery allowed mail to be delivered to more American households than ever before. Billions of postcards were mailed during the golden age, including nearly a billion per year in United States from 1905 to 1915, and 7 billion worldwide in 1905. Many postcards from this era were in fact never posted but directly acquired by collectors themselves. The Plainfield Historical Society is lucky to hold in its archives several examples of these collections from the Clark/Rice family. The example we chose for this exhibit contains postcards collected around 1910, with most having wonderful examples of botanical prints that were so popular in this era.

To see a gallery of the Clark/Rice postcard collection click here.

Post Card History Smithsonian Institution Archives

Photography

With the development of photography, botanical illustration became less significant as the primary method of portraying plants for scientific purposes, and the number of artists also decreased. Botanical photography has risen to new heights. full of highly detailed photographs—often taken with a macro lens or even a microscope—allowing us to discover the fascinating forms of flora and fauna. Below are just a few of Plainfield’s talented photographers.

Robert Benson

Bob Benson (1941-2016), a long-time resident of Plainfield, MA, was a semi-professional photographer, photographing many a wedding and special event. But Bob’s real love was photographing nature, especially the flowers and flora of western Massachusetts. Since moving to Plainfield in 1983, Bob and his wife, Nancy, have lovingly designed and nurtured acres of gardens at their home on Parson Avenue, which inspired many of Bob’s photographs. Bob’s patience for waiting for the right shot and sense of color really comes across in his photos. Besides their passion for all things botanical, the Bensons also founded the Buffalo Village Restaurant, featuring locally sourced buffalo. If you are interested in purchasing one of Bob’s photographs please contact Nancy at 414-634-2228

Pleun Bouricius

Pleun Bouricius is an independent historian, writer, editor, photographer, and the principal of Swift River Press. She is the author of the essay and photo collections, Beech, The Fall and Rise of a Forest (2019) and The Bog (2017), principal architect and author of Hidden Walls, Hidden Mills, a series of history/ecology adventures in Plainfield, MA; and the volunteer curator of the Plainfield Historical Society, where she also authored and designed, with Dario Coletta (photography) the 2010 Barns of Plainfield calendar and a bunch of other stuff. She is president and founding director of the Massachusetts History Alliance.

Pleun is also the author of a checkered career: In past lives, she was Director of Grants and Programs at Mass Humanities, drove a Freightliner Classic around the country for a while; brought the Women, Enterprise, and Society project at Baker Library at Harvard Business School to fruition; and taught history and literature and women’s history for a decade or so at Harvard University. Her undergraduate degree is in history, women’s studies, and photography from Montclair State College, New Jersey; her MA, in English, and PhD, in the History of American Civilization, are from Harvard University.

Pleun was born and raised in Scheveningen, The Netherlands, and lives in Plainfield, Massachusetts with husband Tee O’Sullivan and a dog named Buddy at “three dumps and a swamp”: 24 acres of forested hillside with a mile of stone walls and a bog.

As a professional historian and photographer and curator of the PHS collections, Pleun was instrumental is putting this exhibit together. If you would like to purchase some of Pleun’s photographs or books use the contact form on the website of the Swift River Press.

Botanical Painting

Today’s photographic capabilities are a better means of capturing the beauty and inner working of plants for scientific purposes, no doubt. But well before the invention of the camera, or even the microscope, artists and scientists took to drawing the plants; both for science and visual pleasure. It is an artistic practice as old as ‘art’ itself. And although it was a necessary part of identifying plant life in decades past, it is a process which is still very much alive today. Botanical artists are drawing attention to the issues and opportunities of our times including education, bio-diversity, conservation, and well-being.

Below are just of few of the local botanical artist we highlighted in this exhibit.

Beverly Duncan

Published: 3/1/2019

Beverly Duncan is an award-winning botanical artist, the first to receive Best in Show at the annual exhibition of the Horticultural Society of New York and the American Society of Botanical Artists, of which she is a member. Her work is in corporate and private collections around the world. Beverly exhibited and received recognition for a series of paintings of New England Winter Branches at the 2014 Royal Horticultural Exhibit in London. She teaches Botanical Drawing and Paintings classes at the Hill Institute in Northampton, MA, as well as private lessons in Ashfield, MA, where she resides. Beverly has illustrated commissions for numerous books, magazines and calendars. Her work is represented by Susan Frei Nathan, Fine Works on Paper, (Bio from American Society of Botanical Artists: Beverly Duncan) Ms. Duncan also is an illustrator at Storrey Publishing and floral designer at Gloriosa & Co. in Ashfield, Massachusetts.

“Since arriving in western Massachusetts many years ago, I have focused on drawing plants. First intrigued by wild edibles, I have enlarged my focus, drawing and painting the very local flora and fauna surrounding me, beginning in my gardens and the woods behind my home. I pay attention to what is sprouting, blooming, ripening, and in dormancy in a specific season; many of my compositions combine plants and insects of a time and place. As I observe, sketch and paint, I am always learning more about the interconnectedness of the natural world.”

Beverly was kind enough to lend us a few of her pieces for our exhibit, as well as offering her time one Saturday morning to teach a group of novices the ins and outs of botanical painting.

Commonweeder: Welcome to My Garden The Art of the Plant: Beverly Duncan

Lori Austin

Lori Austin is the secretary and ‘webmaster’ for the Plainfield Historical Society. As a newly retired teacher she is enjoying having more time to devote to her passions; botanical painting, science, history, reading and the great outdoors. This exhibit was right up her alley! Under the mentorship of Beverly Duncan, Lori has been painting local flora for six years. She resides in Plainfield with her husband, Gary and their Welsh Corgi, Quinn.

To see a gallery of Lori’s work click here.

Eliza Melle Healy

Eliza Healy is a professional gardener and has a passion for all things botanical, receiving a BA in Soil Sciences from UMass. Her Plainfield home is surrounded by ever expanding gardens, which are lovingly tended with the help of her two boys, Collin and Ethan. Her delicate watercolors speak to her understanding of the science behind each botanical she illustrates. She too, has study under Beverly Duncan.

To see a gallery of Eliza’s work click here.

We would be remiss if we didn’t mention two other local artists, whose outstanding work includes many botanicals, and that is Plainfield’s own, Larry Preston, whose work can be seen at his website, Larry Preston. The second is Michael Melle, who uses hay to create unique sculptures that can be seen throughout New England. Check out his website at Michael Melle

To learn more about the history of botanical arts click here

Events

We were also treated to a presentation followed by nature walk with Nan Childs naturalist and educator – who kindly allowed us to borrow her flower press

Learn about pressed flowers and how you can enjoy this art form here.

Pamela Weatherbee, author of Flora of Berkshire County Flora of Berkshire County, Massachusetts Pamela B, and Berkshire Museum. Flora of Berkshire County, Massachusetts. [Pittsfield, Mass.]: Berkshire Museum, 1996

US Wildflower’s Database of Wildflowers for Massachusetts

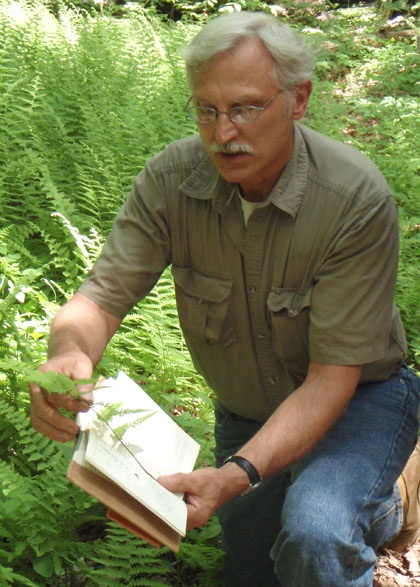

Guided Fern Walk

We were also treated to a Guided Fern Walk by local expert, Randy Stone from the Pioneer Valley Fern Society The mission of the Pioneer Valley Fern Society is to share the enjoyment of ferns with those of mutual interest by observing ferns in their natural environments and in gardens and conservatories; and to provide a forum for exchange of information and opportunities for outreach and education.

Mr. Stone took us on a tour of Dudley and Judy Williams’ West Main Street property, here in Plainfield, where we got to see and learn how to identified at least fifteen different types of ferns common to our region. Judy Williams is the president of the Plainfield Historical Society, and she and Dudley have been instrumental in saving large tracts of wildlife habitat in Plainfield. Read more about what they have done for Plainfield in Judy & Dudley Williams: Heroes for West Mountain.

“A people without knowledge of their past history, origin, and culture are like a tree without roots.”

-Marcus Garvey

A big thank you to all who helped put this exhibit together, including Denise Sessions, librarian extraordinaire; Pleun Bouricius, PHS curator, who help with photographing the exhibit and whose research was invaluable; Linda Melle, who was always there when we needed her and did extensive genealogical on the Shaw/Hudson family; our fearless leader, Judy Williams, whose enthusiasm for this project was contagious; Lori Austin, who researched and created this website; and to all members of the Plainfield Historical Society for their support; and of course, to Robin Sauve, who planted the first seed.

This program is funded in part by the Plainfield Cultural Council, which is supported by the Massachusetts Cultural Council.