Coming of Age in Plainfield:

Women’s Stories of Successful Aging

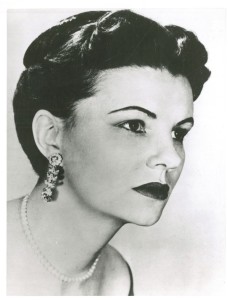

Irene Jordan Caplan: 1919 – 2016

Irene was a writer as well as a singer. To read some of her writings click here.

Irene shared many characteristics with the other women in this study, qualities that help to explain their successful aging. The most important trait each of these women possess is a strong sense of independence and agency, beginning in childhood. Throughout her long life, Irene did not shy away from making difficult decisions. Here, using her own words as much as possible, are 7 decisions that shaped her life. (Click here to read a more complete life history, “Irene Jordan Caplan: Soprano.”)

Decision 1: To become an opera singer

Here’s how Irene told the story in an interview on July 4, 2007:

When I was not quite five years old, my folks took me to see Aida performed by the Chicago Civic Opera in Birmingham. Rosa Raisa sang the title role. So much pageantry! The music was wonderful. The orchestra was great. And I decided that’s what I was going to do when I grew up. My older sister, Martha, laughed at me and said, “You won’t know if you have a voice until much later.” But I said, “That’s what I’m going to do.”

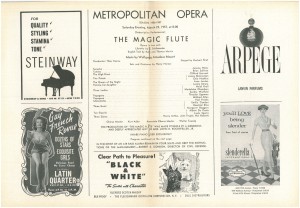

Irene never lost sight of this goal, and at her grammar school graduation, when she was twelve years old, the “class prophet” pronounced that “Irene Jordan will sing on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera.” Irene was pleased by this prophecy and did everything in her power to make it come true.

Decision 2: To move to New York City to pursue her opera career

In 1935, at age 16, Irene enrolled in Judson College, a women’s college in Marion, Alabama, majoring in voice and piano. After graduating in 1939 at age 20, she taught voice in the college’s music department for one year. Then, in 1940 she made another bold decision. She moved to New York City, where she studied voice, ballet, German, French, and Italian. It must have taken great courage for this shy girl from Alabama to move to New York and strike out on her own. But Irene was determined to make her dream of singing at the Met come true.

In 1946, she got her big chance. She auditioned for the Metropolitan Opera as a mezzo-soprano and was offered a job in the Met’s chorus. But she soon got another phone call. The voice on the other end of the line said, “Tell Kurt Adler [the director of the chorus] to take that job in the chorus and shove it! You’re coming in tomorrow to sign a contract to sing major roles at the Met.” From that point on, things moved quickly. Irene explains:

It was a tremendous shock! I was expecting to get advice on whether or not I might eventually have a career in opera. And instead I learned that I was to sing on opening night at the Met—just three weeks away. The situation was this: Lily Pons was to sing the opera Lakmé. She had just done it in Canada with a gal who was assigned to do it at the Met, Martha Lipton. She was a beautiful gal, and she had a nice voice, but she was quite heavy, and she couldn’t move around on the stage. Lily was tiny, and she liked to flit here and there as she sang. She said she was not going to sing on opening night unless they could find a mezzo-soprano who could sing the duet and move with her on the stage. Well, I had been studying ballet for over a year with Nico Charisse, the husband of Cyd Charisse. My feet were never very good, but I could move. I didn’t plant myself in one position on the stage. So here was the Met, stuck, just a few weeks before opening night, and Lily was saying she wasn’t going to do it. I just fit the bill.

And so, on November 11, 1946, Opening Night for the Met’s fall season, Irene made her debut on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera. Asked to comment on this momentous evening, Irene minimized her accomplishment. “It wasn’t a heck of a lot to learn for opening night. I really wasn’t very nervous. I just had this lovely duet with Pons in the first act. She was very pleased with me because she could flit around the stage, and I could go with her.” It may not have been a lot to learn, but the opening night audience would have been waiting for this piece, the hauntingly beautiful Flower Duet from the well-known opera by Léo Delibes.

Decision 3: To marry Arnold Caplan

It wasn’t long before Irene attracted the notice of a young violinist in the Met orchestra recently home from the service. Irene remembers:

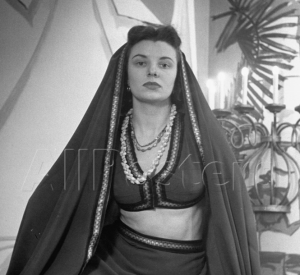

I was playing the role of a Hindu servant in Lakmé. I wore a midriff costume, quite beautiful, and I had to wear dark body paint. It was a big job to wash it off. And when I met Arnold, I thought, “Oh, he’s gonna see me all washed out, you know, the way I am, and he won’t be interested in me at all.” Later on when I told him about that, he said, “Look, I had seen you in rehearsal for several weeks so I knew what you looked like.” So I was worrying for nothing. He had seen that I wasn’t that exotic Indian color.

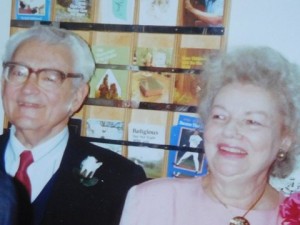

The romance moved swiftly. Arnold and Irene were married in Birmingham on June 10, 1947, at the end of Irene’s first season at the Met. This was a love affair that lasted. Arnold died on July 8, 1997, one month after their 50th wedding anniversary.

Decision 4: To become a soprano

Irene was having great success as a mezzo at the Metropolitan Opera. In her first season, she performed 49 times with the Met, more than any other singer. An article in Life magazine from 1946 described Irene Jordan as “the Met’s prettiest new star.” But in the late 1940s she made another major decision, one that would shape the rest of her career. Here is how she described it in her professional bio for 1959 (included in the program for her performance as a soloist with the New York Philharmonic at Lewisohn Stadium in New York City on June 29, 1959):

…[Miss Jordan] recognized the possibility of extending her range and building the power of her voice and had the courage to turn down a Metropolitan contract renewal, withdraw from professional activity, and devote several years of intensive re-study toward the new artistic goal she had set for herself. Her re-emergence as a dramatic coloratura in Thomas Scherman’s 1951 revival of [Carl Maria von] Weber’s “Euryanthe,” established with stunning impact the wisdom of her decision….

Irene Jordan, dramatic coloratura, “Orpheus in the Underworld,” Stratford (Ontario) Shakespeare Festival, summer 1959

Decision 5: To combine child rearing with an opera career

It wasn’t long after Irene’s marriage to Arnold in 1947 that she became pregnant, but she didn’t announce her pregnancy and continued to perform in her second season at the Met. Finally, she gave notice that February 12, 1948, would be her last day. But the baby had other ideas. Joel Caplan was born on February 6, two months before the expected due date.

Like her mother before her (Irene was one of 10 children), she made a conscious decision to combine music, marriage, and child rearing. We can sense the pride she took in her multiple vocations in this excerpt from her professional bio that appeared in the program for her June 29,1963, Stadium concert with the New York Philharmonic.

The wife of Arnold Caplan, a fellow southerner who is a violinist in the Metropolitan Opera House Orchestra, Miss Jordan is the mother of a quartet of little Caplans, ranging from 14-year-old Joel, 12-year-old Rosebeth and 8-year-old Rowen to David, who has just turned 6. The Caplans live in a rambling old-fashioned house on a half acre of wooded land in New Rochelle, NY.

Not many divas have such a rich family life, and if they do, they certainly don’t highlight it in their official bios.

The following anecdote from “The Alabama Baptist” reveals the conflicts Irene experienced as a mother pursuing a serious opera career.

[Irene Jordan] Caplan was once offered a contract to go to London, but she wasn’t sure if it was God’s will for her. She was pregnant at the time and was afraid of the timing of her travel. “I wanted to sing opera, and I had this lovely opportunity,” Caplan said. So she opened her Bible, and God gave her Psalm 126:6. She felt that verse was God’s way of telling her that she would be OK and that she should go [to London].

Here is the verse she read:

Those who go out weeping,

carrying seed to sow,

will return with songs of joy,

carrying sheaves with them.

Obviously, Irene had no problem making difficult decisions, but sometimes she got help from a higher power.

It was during this trip to London that Irene performed the very difficult high soprano role of the Queen of the Night in Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute at Covent Garden. The esteemed conductor Bruno Walter was in the audience for one of these performances, and he commissioned Irene to sing the same role when he conducted this opera back in New York at the Metropolitan. Irene did indeed perform the Queen of the Night at the Met on March 23, 1957. Unfortunately, though, Walter had suffered a heart attack and was not able to conduct.

The reviews of this performance were mixed, and as fate would have it, this turned out to be Irene’s only performance at the Metropolitan Opera as a soprano, a source of lifelong regret.

However, she did go on to have an absolutely stellar career as an artist, singing major roles all over the world, performing new and challenging works, and teaching voice at prominent universities and schools of music—a career that lasted for the next 50 years.

Decision 6: To commission Giannini rather than Copland

Throughout her career, Irene put artistic integrity ahead of professional advancement, and at least in one case this may have resulted in the loss of a powerful champion. Here’s how she told the story to her sons.

In 1959, Irene was nominated by Leonard Bernstein for a Ford Foundation grant to be awarded to the “Top Ten American Performing Artists” to show “public appreciation of the richness and variety of America’s musical resources at their highest level.” It was a major triumph when Irene was one of the winners. And her reward was to choose a composer to create a major work specifically for her. Bernstein wanted her to select Aaron Copland to compose the piece, but she declined because she didn’t care for his compositions for the voice.

Instead, she commissioned the Italian-American composer Vittorio Giannini to compose a piece for solo soprano and symphony orchestra. The resulting composition was a 40-minute, 4-movement “monodrama” entitled The Medead. It was based on the ancient Greek drama of Medea, who kills her own children in order to punish her unfaithful husband, Jason.

When The Medead premiered in 1960, it was a great success. Walter Simmons, a musicologist and music critic, regards it as “one of the greatest works of the 20th-century.” This is how he describes Irene’s performance (on the 2-CD set released in 2015, available from Norbeck, Peters & Ford http://www.norpete.com/v2459.html):

What is most striking about the soprano we hear in The Medead is her power and intensity, unblemished by ugly moments of loss of control or of imprecise pitch—and these are live recordings! One realizes that Giannini and Jordan fully understood the expectations each held of the other.

But one person was not happy. Leonard Bernstein stopped returning Irene’s phone calls.

Decision 7: To keep on singing

Fortunately, for those who only knew Irene when she was in her 70s and 80s, she did not completely retire from singing as many opera stars do. She continued to give concerts in Western Massachusetts and often sang solos at the Plainfield Congregational Church, where she also sang in the choir. Listening to Irene sing was always an emotional experience. She seemed to become one with the music, using her remarkable voice and dramatic delivery to tell the story of the song.

When Irene was a young woman, the famous conductor Leopold Stokowski told her: “You will sing as long as you live.” “Why would you say that?” she asked him. And he replied, “When I was a young man studying in Italy, I heard that kind of technique. I have not heard it in a long time.” Stokowski’s prophecy proved correct.

Irene’s last major public appearance was in the summer of 1999 at age 80, when she performed Brahms’s “Songs for Voice and Viola” at the Mohawk Trail Concert Series in Charlemont, Massachusetts. Seven years later, when she was 86, she traveled to Birmingham, Alabama, to attend a reunion for alumnae of Judson College, her alma mater, where she was scheduled to sing. She told the audience, “I don’t have the right to be singing at my age, but I am going to attempt it.” She went on to sing two of her favorites, “Sweet Little Jesus Boy” and “A Place Called Heaven.”

Irene’s mother, Sarah Ann Whitehurst Jordan, another remarkable and determined woman and musician, often told people that Irene’s voice was “a gift from God.” Many who heard her sing would agree. But Irene also worked very hard throughout her long life to develop the gift that God had given her and to share it with others.