In Search of the Plainfield Town Pound

As always, all blue highlighted text and photos are hyperlinks.

Plainfield Town Pound

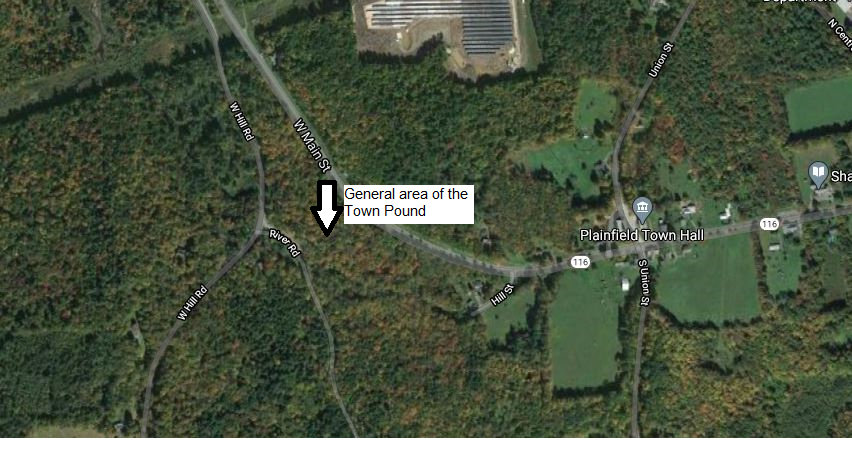

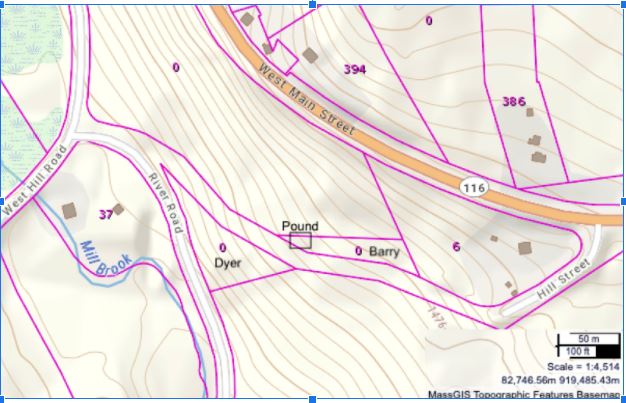

Map of Town Pound Location

For years, two of the Plainfield Historical Society’s members, Dario Coletta and Matthew Stowell, have been on a quest to find the Plainfield Town Pound. After hours of searching the Town deeds and reports, reading through the copious notes left behind by Arvilla Dyer and her sister, Pricilla Allen, and many hikes through bramble and mud, they have finally found it!

Dario’s expertise in dry stone, running D.C. Stoneworks out of his home in Plainfield, a professional member and instructor at the Stone Trust, as well as being chair of the Plainfield Historical Commission, and vice president of the Plainfield Historical Society, all lead to a piqued interest in finding this old stone structure. And Matthew, whose interest in Plainfield history began when he was conducting research on the Stowell family’s genealogy in Plainfield’s Town Records during his summer’s “off” as a history teacher, has a natural instinct for scooping out historical conundrums. His ancestors were some of the founding families of Plainfield, who, along with many Plainfield residents of the mid-1800s, emigrated to the Ohio region, what was then considered the “Wild West.” They left due to poor farming, depleting natural resources, and better economic opportunities. While conducting research Matt fell in love with the town and eventually bought and rehabilitated the “Brick House” in Plainfield Center. Once Matt moved to Town his interests expanded and he began unraveling the many mysteries uncovered in these town records. He stumbled upon records of a “town pound” and he and Dario set out on their quest. After years of searching they finally had their “eureka-moment”

Dario writes, “I think the primary reason I was not able to locate the pound previously comes down to the town report that states that the new stone pound from the 1807 be built “on the north side of the road about 40 rods west of Joel Carr’s.” In measuring 400 rods (660’) west from that foundation, I found myself almost at the bottom of the hill near River Road, and thus I centered my search in that area.

In retrospect, the phrase “about 40 rods” is key as it appears this was an approximation and not an actual measurement. I also assumed there was a direct entrance to the pound off the road, but as it turned out, one has to walk approximately 300 feet off the road to get to the pound.

As I discovered, this bit of land, triangular in shape, is flat, unlike the rest of the land north of the old road, making it a logical spot for the pound. I would not have been able to discover this without Matt Stowell’s deed research which showed a triangular piece of land whose north side was designated as being part of the pound.

As Matt and I walked this triangle and approached the corner, it became obvious to us both almost simultaneously that this had to be the pound: Four walls, 30’ x 30’ perched on a huge piece of ledge perhaps 50’ above the old roadbed, making it difficult to see when walking up the road.”

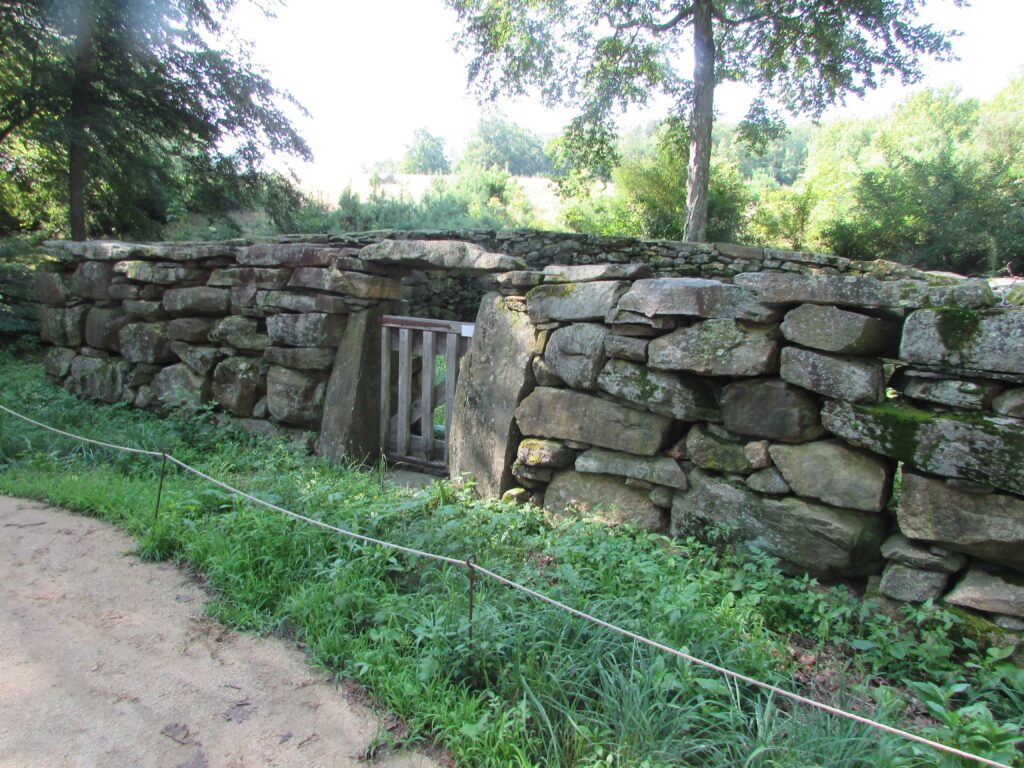

Plainfield’s first “town pound” was located in the center of town, where Main Street and Central Street meet. It was a small, unused log cabin-like structure and served the town from 1789-1798. Town records indicate that this structure soon became insufficient and a long search for a new site for a stone structure was started. The old wood of the pound was auctioned off to Josiah Torrey for 80 cents in 1807. Read about this process in a Timeline of Plainfield Pound from1785 to 1964, compiled by Matthew Stowell. The stone town pound measures 30 ft. by 30 ft., and had a south wall 6 ft. high and a north wall 5 1/2 ft. the other walls leveled between them. The base would have been at least 3 ft. thick. Time and erosion has taken its toll.

“Generally similar in size — roughly 30 feet by 30 feet — and height, these stone pens vary in construction method, often a function of when they were made. An old farmer’s saying advised that stone pens be built “horse-high, bull-strong, and hog-tight,” which is why the pounds that still exist are some of the finest examples of Colonial wall-building, writes Gary Santaniello in his article Have You Found a Town Pound?

History of Town Pounds in New England

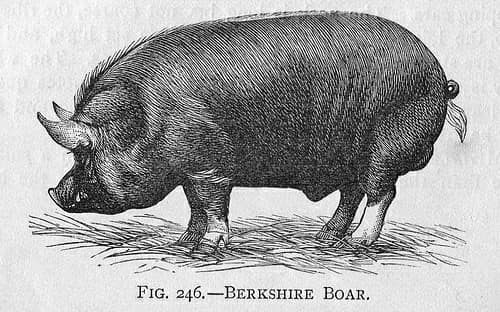

During the 18th and 19th centuries it was not uncommon for towns throughout New England to establish a “town pound” where stray animals, such as cattle, sheep and swine, especially swine, could be held until they were claimed by their owners. For a fee, of course. As Plainfield was mainly an agricultural community, folks often let their farm animals wander the woods and fields, foraging for food, such as acorns, beech nuts and chestnuts, juniper berries, slugs, insects, worms, fern roots, and fungi. These wandering domestic animals also would traverse land owners’ walls and fences, so it was not uncommon for these animals to “escape” onto other’s property, where they often would cause damage to crops and gardens and a general annoyance to town residences. Eventually both local and state governments created “town pounds” to alleviate these nuisances.

Town pounds according to Sermons in Stone by Susan Allport and Town Pounds of New England by Elizabeth Banks MacRury were part of early colonial history. In Massachusetts pounds date back to 1635. Early pounds were constructed of wood fencing which often had to be rebuilt. Stone-walled pounds began to replace wood pounds around 1740, and by 1800 stone was the favored building material. Town pounds were in common use from the mid 1600’s to the late 1800’s. Stray animals, and those often taken for tax purposes were kept in Town Pounds as a way to enhance a town’s finances.

Photo by Bill Coughlin

“The first pounds in New England were built in the early 1600’s and were made of wood. In the mid-1700’s, these structures began to be replaced by stone walls, better able to stand up to the occasional stray bull. Today perhaps a hundred town pounds remain across New England. (They exist in other areas too. In addition to having mapped two dozen of New England’s pounds, users of the site waymarking.com have located one in a Nevada ghost town, and several in the U.K.)”

As mentioned above, hogs caused the most nuisance and destruction to property, thus the person charged with managing these town ponds was the hogreeves. In some towns they were known as “Pounders”.

“A hog reeve or hogreeve, hog-reeve, hog constable is a Colonial New England term for a person charted with the prevention or appraising of damages by stray swine. Wandering domestic pigs were a problem to the community, due to the amount of damage they could do to gardens and crops by rooting.

The owners of hogs were responsible for yoking and placing rings in their noses. If the hogs got loose and became a nuisance in the community, one or more of the men assigned as a hog reeve would be responsible for capturing and impounding the animal. If the animal did not have a ring in its nose, then the reeve was responsible for performing the necessary chore for the owner, who could legally be charged a small fee for the service. There were punishments and fines established for failing to yoke hogs and to control animals. . In New England, the owner of a stray hog in the town of Chelsea, Massachusetts would be charged 10 shillings per hog.

The office originated in Anglo-Saxon England, when hogreeves would be stationed at the doors of cathedrals during services to prevent swine from entering the church. The office of hogreeve was among the earliest elected offices to exist in colonial North America; the earliest rights specifically granted to towns in New England concerned the herding of swine, cattle, and the regulation of fences and common fields. The field driver held similar duties but was not restricted to swine. The hogreeve was a historical municipal official in Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island in Canada; it was also listed as an elected office in early New Hampshire township records.

In Massachusetts, towns could vote to stop enforcement of the state law against letting swine run loose; many towns did so, leaving their hog reeves with nothing to do. As a result, it became a joke to elect a man hog reeve during the first year of his marriage.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hog_reeve)

In the article, New England Is Riddled With These Mysterious Stone Enclosures, Johanna Kaplan writes, “Even in the past, the post of pound-keeper was treated as a bit of a joke. The job was taken seriously enough that appointees swore a “Pounder’s Oath,” but it was unpleasant (pounders had to be on call to wrangle wayward animals when needed) and it didn’t pay well (a pound-keeper had to feed animals at his own expense, hoping for remuneration when the livestock were retrieved).”

Today the Plainfield “town pound” and the land around it, has a lien on it due to years of unpaid back taxes. The Plainfield Historical Commission will be speaking with the Select Board to discuss the process of foreclosure on this property so it can be returned to the Town and conserved.

Plainfield no longer has a town pound but instead has a Plainfield Animal Control Officer, assigned office space at the Plainfield Police Department. The Animal Control Officer is on call 24/7 to meet the needs of the community. The Animal Control Officer (ACO) responds to citizen complaints or concerns, which are received through dispatch and directed to the ACO, regarding all domestic/ wild animals. The Animal Control Officer can be reached regarding non-urgent animal concerns via phone or email.

To read more on town pounds click on any of the links below:

See Town Pounds throughout New England at Stone Structures of Northeast United States

Town Pounds by Kaushik Patowary