The Shaw and Hudson Families: Members of the Plainfield Community

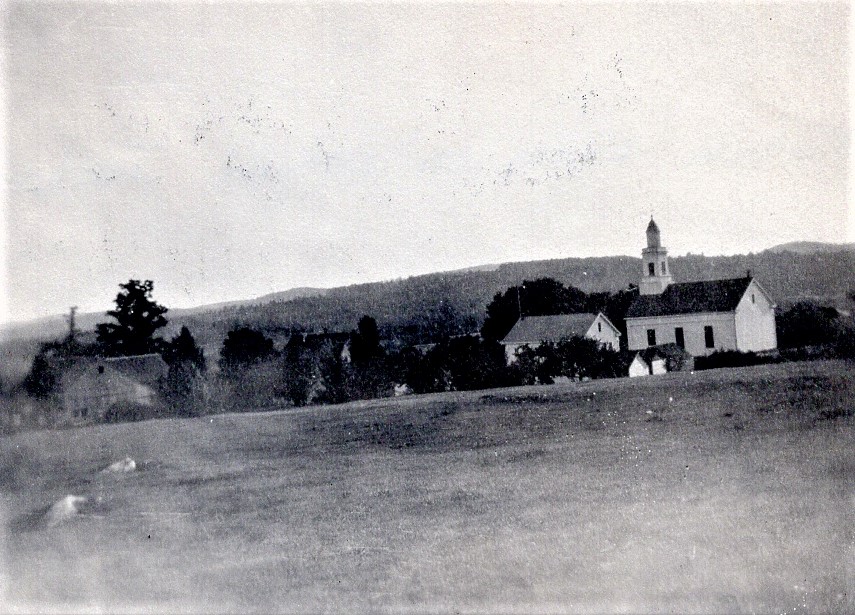

From this South facing bedroom, one can look through any window and past the center of Plainfield, far out onto the surrounding hills, as we are sure the Shaw and Hudson families often did. While many members of the family moved away from Plainfield, it remained their summer home and place of refuge from the congested cities of New York and Philadelphia.

Plainfield was fortunate to have this family as part of its community, for besides having two doctors who practiced in town, family members played an important role in helping to assure safe drinking water, adequate health services for Plainfield’s children, played a pivotal role in establishing a town library, and served on the Plainfield school committee.

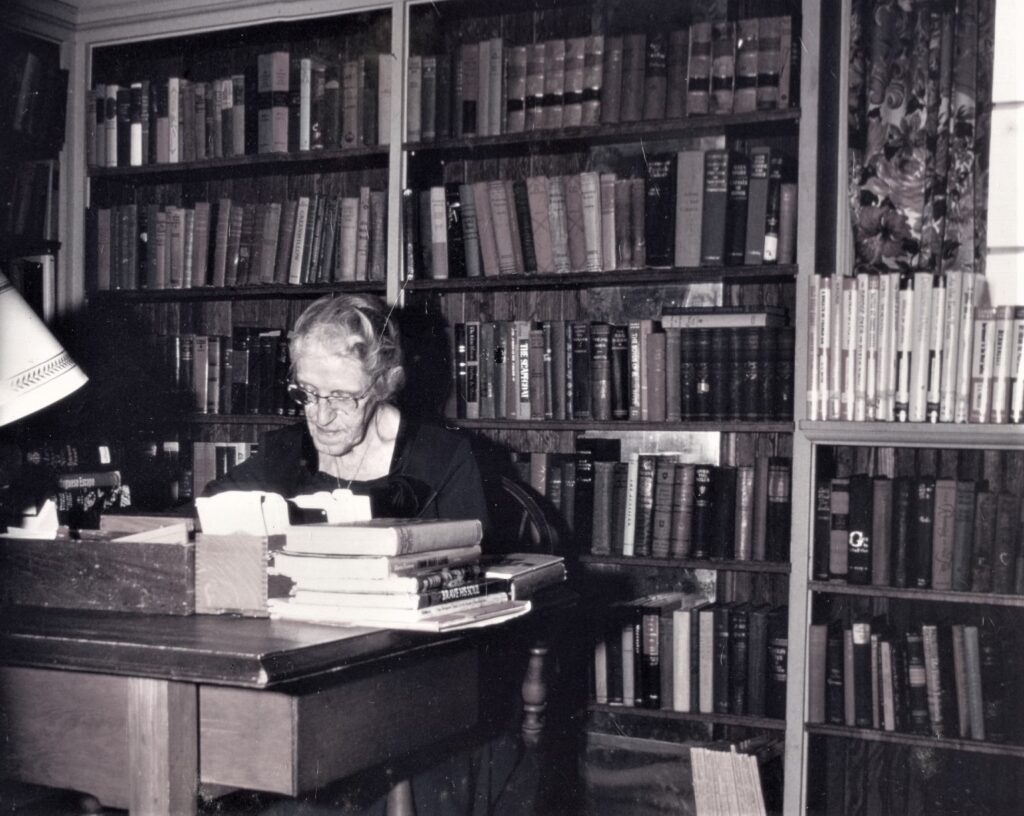

The following are excerpts from The Romances of a Country Doctor, a paper read at the annual meeting of the Northampton Historical Society at the Unitarian Church, Northampton, on October 7, 1947 and Plain Tales from Plainfield or The Way Things Used to Be, 1962, both by Clara Elizabeth Hudson. Ms. Hudson was a granddaughter of Dr. Samuel Shaw and the last surviving relative to live in the Shaw Hudson House.

Click on photographs to enlarge and all blue highlighted text for a hyperlink to more information.

Plainfield Aqueduct Company

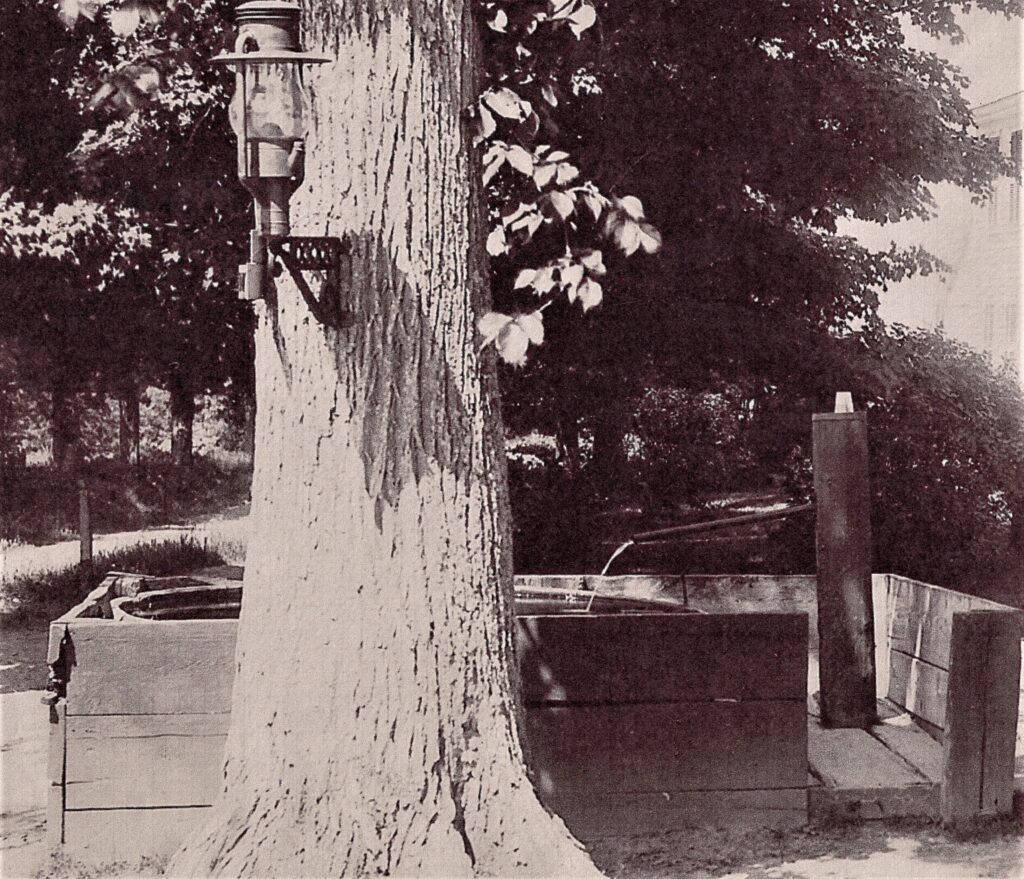

“My grandfather, Dr. Samuel Shaw, was one of the dozen or so members of the Plainfield Aqueduct Company, an association of householders formed in November, 1816, whose dwellings were near the junction of Main and Central Streets. In quest of a source of good water, they found an excellent spring in a spot high enough for gravity to furnish the force necessary to keep water running continuously at the level of the houses. The water was tested in Boston and found to be very pure.

The water was conducted through logs, probably spruce of which had been made hollow by boring. One end of each log was pointed sufficiently to fit into the end of another log. The lines of logs terminated near a cistern at the crossroads of Main and Central. From this point individual pipes of lead conducted the water to the various houses, where it ran continuously into and out of a water barrel.

I believe that after many years’ use the logs were replaced with iron pipes. In later years, when the flow of water was less, faucets were installed at the houses and a gauge was placed on each pipe at the point of distribution. This made possible equal sharing of the water by the various families.

The company at its annual meeting elected one of its members as superintendent and he was responsible for making all necessary repairs. Bills were tuned over to the treasurer, who collected from the members after they had voted to assess themselves for the bills’ total. One year each family’s bill was 69 cents. In later years the company voted to levy annual dues of $4.00, as a nest egg to provide for possible extensive repairs.

For many years I was secretary-treasurer of the Aqueduct Company and the only woman representing a family. We met in H. S. Packard’s brick store at the corner of Main and Central. The men sat on the counters and swung their legs, while I was furnished with a chair.“

Plainfield Congregational Church

“The Shaw pew in the Plainfield church was in front of and at right angles to the main body of pews. Grandfather had helped in the building of that church and this “cross-way” pew had been allotted to him so that if he were needed professionally, in case of an emergency during church service, a messenger beckoning from the central doorway could be seen. Some wit called this type of pew a “showcase.”

During part of World War I Plainfield’s only church (Congregational) was without a settled minister, the pulpit being supplied by visiting clergy. One Saturday evening someone whom I cannot now recall pounded on our front door’s iron knocker with Dr. Samuel Shaw’s name on its brass plate and asked for me. The pulpit supply had been taken ill and was unable to serve the following day. Would I take charge of the service? (In those days of few local telephones there was no way to cancel the service.) I remonstrated, asking: Why not get a deacon [there were three at the time] to serve?” The answer was: “One is out of town, one is sick, and one stutters.” Under those circumstances what could I do but promise to help as best I could? Although a Unitarian, fortunately I had at hand a few excellent sermons written by the man who had started the Christian Endeavor Society of the Congregational Churches. Selecting one, I read it over and over until I could deliver it without gluing my eyes to the script. I selected my favorite hymns and wrote my own prayer. Dressed in a simple tailored suit and an untrimmed pill-box type hat, I conducted the service from a lower level than the pulpit, and at the end of the service I used the Christian Endeavor Benediction, “May the Lord watch between thee and me while we are absent one from the other.“

A few weeks later choir practice at a neighbor’s house was interrupted by the announcement that the expected preacher for the next Sunday had ‘fallen by the wayside’. Would I again take charge of the service ? While inwardly much pleased that my service was considered good enough for a second attempt, I raised one question. Four of us had practiced thoroughly a musical quartet, and another alto to replace me could riot easily be obtained. As the organ and choir were directly behind the pulpit, the solution of the problem was for me to occupy the pulpit itself. After I had handed the ushers the baskets for the offering and said the usual offertory phrases, “Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works and glorify your Father which is in heaven,” I could go up the two steps to the higher level where the choir would stand. The ushers, after receiving the offering and before coming forward, would give me time to return to the pulpit. Again I selected one o£ Father Endeavor Clark’s sermons, practiced reading it, chose my hymns and wrote my prayer.

When Sunday came I was somewhat less nervous than on the previous occasion and all began well. But after I said the offertory sentences I was tired – so I sat down. There was a slight pause; then the tenor leaned forward and in an audible stag whisper, said, “Coming up?” Somehow I finished the service without further errors, but whenever I have been where an elevator boy has said, “Going up?” into my mind has come the memory of that Sunday morning in Plainfield and of the tenor’s s summoning me to join the choir.“

Child Welfare in a Country Town

“In 1916 a life insurance company offered a five dollar gold piece as a reward to the baby who, in any town in a certain district, was proved healthiest by examination. After consulting with the pastor and with his wife, I arranged for the contest, sent away for the gold piece, and engaged the so-called conference room on the ground floor of the Plainfield Town Hall as an examination room, and the adjoining center schoolroom as a place in which waiting mothers and children could sit. Although Plainfield then had no resident physician – the townspeople divided their allegiance between the two doctors who lived in the nearby town of Ashfield – I was fortunately able to secure the services of a Dr. Streeter of Pittsfield, who was our state district health officer.

The next step was to clean the rooms. Cynthia Nye, the chairman of the Board of Health, didn’t know anyone who could be secured to do this, unless she herself took on the job. Since she lived several` miles away, I seemed to be the person indicated to turn scrubwoman. As there was no ruining water in the building, nearby friends promised plenty of hot water and I tock my cleaning utensils and some disinfectant with me on foot from my home over a quarter of a mile away. That evening a man on his way to some social event in the Town Hall on the floor above sniffed and ejaculated, “Antiseptic!”

The competitive clinic was well attended, the children obtained valuable physical examinations, and a little French-Canadian boy, Noel Chabot, won the coveted five-dollar gold piece. As each child’s record sheet showed a number instead of a name, the doctor knew no name, selecting the winning child by number only. Hence, no possible favoritism could be shown.

The next year no clinic was held. There was no gold piece to act as an incentive, I was not free to promote it due to sickness in my family, and, as usual, there was apparently some jealousy and criticism by parents whose children had not won. The succeeding year, however, the clinic was again held, although the last I knew it had been discontinued. As far as I ever learned, Plainfield’s “Well Child Clinic” was the first one held in Hampshire County. I believe that pre-school clinics are now held.“

Because the teeth of our school children needed attention, we turned to the Red Cross for help. Luckily the Red Cross director had already been discussing the possible need for local dental work. When Plainfield requested such service as soon as possible, the Red Cross in 1921 engaged the dentist for us and bought portable equipment. Besides serving Plainfield the clinic ultimately worked in fourteen other towns for over twenty years, averaging 3,500 operations a year. Owing to World War II the Red Cross had to discontinue the clinic in 1945. It had been an isolated, pioneer project and the Red Cross had to concentrate on projects common to all its chapters. Many of the towns served by the clinic

continued to have dental work done on their own responsibility.

Besides needing much dental work, several pupils were adenoid cases. I asked the doctor what the parents usually did when he received notices from him listing the defects their children had. He said the notices apparently went into the wastebasket. Realizing the difficulty of having these conditions corrected because of the distance from medical help, I decided that I had better see personally what could be accomplished. First I went to call on the parents of one girl who had bad adenoids. Though I tried to be tactful, the father, after practically telling me to mind my own business, said that he didn’t intend to do anything about the matter until he got “good and ready.” Ultimately he did have his daughter’s adenoids removed.

The other child was a girl for whom no funds were available. I don’t remember how we financed the operation except that the Hampshire County Children’s Aid Association was very helpful. In later years this girl – now a

grandmother – told me that before the operation she had never been very well but after it her health was excellent.“

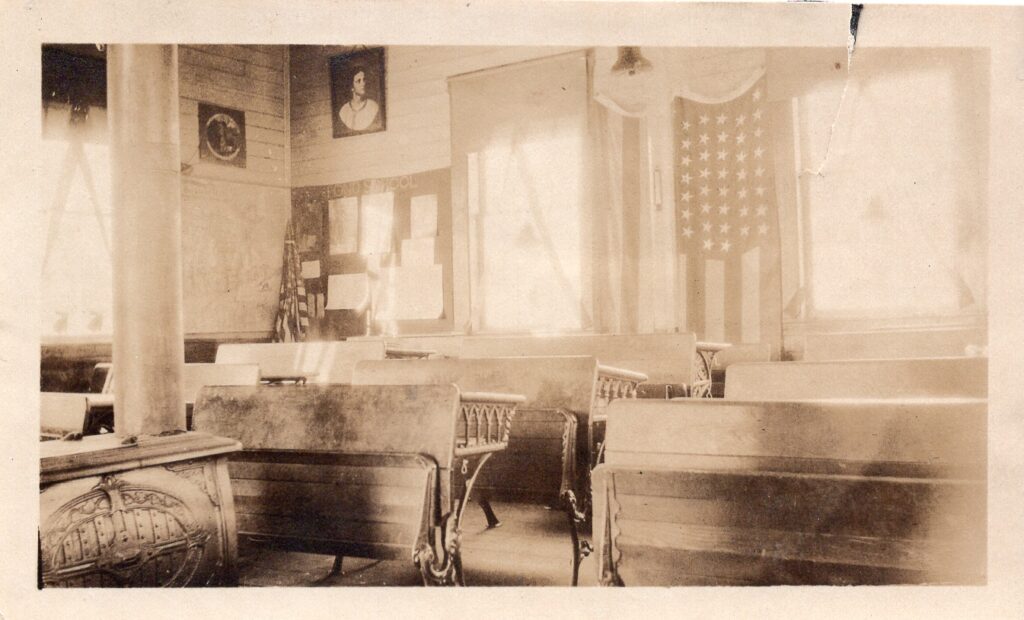

The Schools of Plainfield

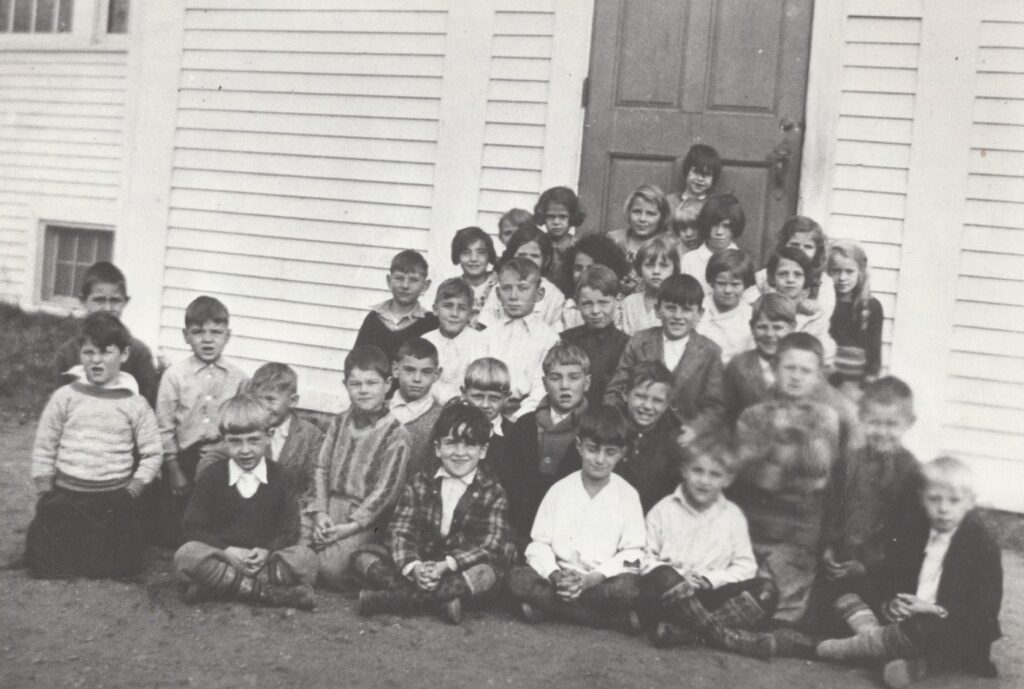

“Plainfield used to have five district schools. The center school had an enrollment of some twenty pupils, although another of the schools had often as few as six scholars. To obtain teachers was difficult, especially as they had to board with a sometimes not-too-near farm family. I knew one teacher who used to snowshoe at times to school and on occasion had to crawl over a snowbank on “all fours.

My mother and I at this time were in the process of raising by gifts from friends the $22,000 which ultimately built the three-room building for the two-room centralized Hallock Memorial School and the one-room Shaw Memorial Library.

One small school was mainly composed of a half-dozen of more state-ward boys who were “placed out” in neighboring families. One solitary, small girl seemed to carry on very well in their midst. The youngsters happened to be unusually good singers, and the “North East” boys were often asked to sing at local entertainments. One foster mother invited me to visit her and her half-dozen state boys for a week. I did not accept.

The school doctor was an old friend of my family and he readily agreed to take me along in his horse-drawn buggy when he visited the schools to examine the children. On the day that we visited the North East School we discovered that one of the state wards who lived at a Mrs. Chabot’s had disappeared while at school. On our way home the doctor and I were to pass Mrs. Chabot’s house, so the teacher asked me to tell her that one of her wards had run away. Approaching her house we saw her hanging clothes out in the yard. Since she was a French-Canadian and spoke little English, I thought that I had better address her in French. As I could not think of the French word for “runaway, I called in my best French, “Mrs. Chabot, Johnny So-and-so has disappeared!” Not in the least disturbed, she responded in perfectly understandable English, “Ahh, bad boy -skipped!”

Sometime around 1918 I was elected a member of the Plainfield School Committee. This was a complete surprise to me. Before cold weather began, my mother, my Aunt Sarah and I always closed the “Dr. Samuel Shaw House,” which grandfather had bequeathed to his daughters, and migrated for the winter to Northampton, where we stayed at the very nice Crescent Inn at 267 Crescent Street. So when Plainfield town meeting was held in late winter I was not present. I always suspected that I might have been elected because no one else would take the job.

I was told, however, that I was chosen in appreciation of the fact that my mother and I had secured most of the funds for the Hallock Memorial School.

There were two other members, both men. One was a very kindly and practical neighbor. The other was an elderly, positive Scotchman, causing people to prophesy, “How John Dalrymple and Clara Hudson will fight!”

Some months later a meeting was held of our Superintendence Union. This union was composed of twelve people – the School Committees of three each from Ashfield, Cummington, Goshen and Plainfield. These four towns were served by the same Superintendent of Schools. Again I was surprised when I was elected Chairman of the Union. The retiring chairman, who, if I remember rightly, was a farmer, gave as a reason for not further that he couldn’t give the time the job needed. All seemed to feel that I had much more time than any of the others. accepted-little knowing what I was assuming.

During the summer, while I was hoeing in my vegetable garden, the Superintendent of Schools called on me, bringing the disturbing news that he was resigning to take a similar {but doubtedly better paying) position elsewhere.

I don’t remember how we learned of three candidates for our empty position, but three there were, each submitting several refences. The secretary of our committee lived in Goshen and ran a market. As neither he nor I had a car, and since we needed avoid any unnecessary delay, it seemed best for me to be the one to write at once to all the references. As soon as the responses were received, the date for a meeting was set, and the three candidates were requested to appear before the joint board.

We met in Goshen, where the candidates were interviewed one by one. The committee had agreed that we would ballot on all three, drop the one who received the fewest votes, and then decide on one of the other two. This we did and the least desirable was dropped and took his leave. In a few days I received a highly complimentary letter from him. Among other things, he said that he had exaggerated his qualifications and that he realized I had seen through his deceit – which I hadn’t.

One of the other two men was past middle age and his references spoke of him as eccentric and as a person who never voted. His highest position to date had been as head of an academy in a country town. The second man was much younger, unimpressive, and he lisped. All of his references were good. They advised us not to be prejudiced by his personality and emphasized the fact that his pedagogy was excellent.

As one of our committee was absent, eleven of us had met. I was presiding over the meeting and did not ballot. The possibility of a tie vote hadn’t occurred to me, but that was just what happened. The dismaying result was that I had to choose the new superintendent. In spite of his lisp, without any hesitation I chose the younger, progressive man. I never regretted it.

As none of us on the Plainfield committee had a car, Dr. Arthur Streeter, a Cummington veterinarian and a member of that town’s school committee, drove us to and from the meeting. I can’t imagine a more unpopular woman than I on the drive back to Plainfield with Dr. Streeter and the two men from Plainfield. All had voted for the older candidate. At the corner by my house we all parted company. Mr. Loud lived just across the road, Mr. Dalrymple across the valley to the west of the town. Before starting for his home on West Hill, the Scotchman’s parting fling at me was, .’Well, I hope you’ll dream of your small boy tonight.”

The next morning, seeing Mr. Loud in his yard, I went out and said, “Mr. Loud, I feel very badly that you think I voted for the wrong man.” To my surprise he answered, “I think you showed more sense than I did. I think the older man would have had the town by the ears in three months, but I couldn’t bear to vote for the young man- he looked like such a sissy.”

Someone apparently told Mr. W. that I was responsible for his election. Sure of one intensely interested board member, very frequently, his car parked in front of my house, he talked over with me the progress he was making. He was progressive but not radical – altogether he seemed very sensible. Some of my friends copied the Scotchman in calling him my “small boy.”

Taking seriously my position on the Plainfield school board, I called on all the mothers in the town who had children in school and I learned much about their problems. Having no easy means of transportation, I did it all on foot.

During the time that Mr. W. was our superintendent Plainfield had five one-room schools, one school in each corner of the town and one in the center.“

Plainfield’s Library

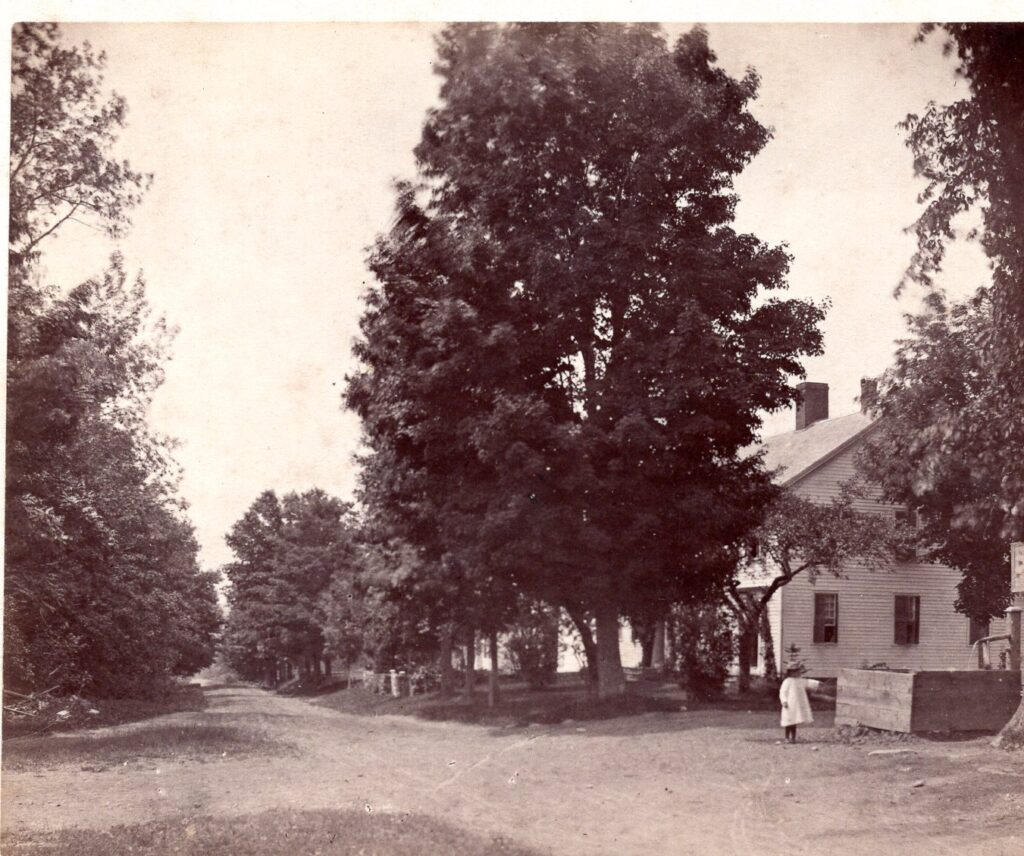

The Library at the Parsonage in Plainfield, MA. ca. 1900 Photo property of the Plainfield Historical Society

“The Plainfield Public Library owes its beginning to the interest and efforts of Mrs. Julia Gurney Sears, who solicited books and gave the use of a room in her house on Central Street, near the upper crossroads, later the residence of Gaetan Beaudoin. Plainfield was one of the first towns in Massachusetts to take advantage of an act establishing public libraries and allowing state aid. In 1891, one year after the act was passed, the local library was established and given $100 worth of books from the state -the first of annual gifts from that source.

The first date on which the library was mentioned in Plainfield town reports was 1892 and the first statement in town reports of $25 being voted annually for library use was in 1896. In 1901 this amount was increased to $35. Mrs. Sears died in 1902.

For about twenty years the library was housed in a room in the ell of the parsonage on Main Street. During this period the librarians were: Miss Anna King (later Mrs. Anna Tirrell), Miss Bessie Holden, Miss Hattie Parker (later Mrs. Newton Lincoln) , Mrs. Martha Stowell Smith, and Miss Florence Bliss.

In 1904 there were 1,279 volumes in the library. A card catalogue was made in 1911. The books are marked by the Dewey system. As Miss Clara Hudson remembers that she and her mother, Mrs. Laura Shaw Hudson, had written over a thousand cards for the card catalogue file, the collection of books must have greatly exceeded that number. By 1925 the number had increased to 3,087 books. Mrs. Smith not only gave devoted service as librarian but, at her death in 1922, left the proceeds from her estate to the library.

In a large house on Maln Street the Reverend Moses Hallock, Yale graduate (1788) and first pastor of the Plainfield Congregational Church (1792-1837), had had a famous “Classical School.” He furnished tuition and board for $1 a week. For some time Williams College was largely dependent for its freshman class on the graduates of Parson Hallock’s school. Among his pupils were: James Richards, missionary to Ceylon and one of those who prayed the American Board of Missions into being

under a ‘haystack’ in Williamstown; ]onas King, first missionary to Greece; William Richards, missionary to the Hawaiian Islands; Pliny Fisk, missionary to Palestine; Levi Parsons, missionary to Palestine; Homan Hallock, missionary to Smyma, who made the Arabic type for printing of the Bible in that language; William Ferry, missionary to the Indians; Marcus Whitman, who saved Oregon for the U.S.A.; John Brown of Harper’s Ferry fame; William Cullen Bryant, famous poet of Cummington and later editor of the New York Evening Post; Gerard Hallock, who established the Journal of Commerce in New York City. Mr. Hallock had also been editor of the Boston Telegraph and Recorder and later the New York Observer.

Over 300 students – including 30 girls ~ attended this school between 1793 and 1824, and Plainfield claims to have sent out more men of eminence than any other town Of its size in the Western Hemisphere. An inscribed stone, in memory of this famous old school, given in 1925 by one of the Parson’s descendants, Mr. Charles Hallock, stands on the lawn in front of the site of this famous dwelling. After Reverend Moses Hallock’s death, July 17, 1837, various families occupied the house until it was destroyed by fire on August 10, 1916.

Mrs. Laura Shaw Hudson had been approached some years

before by the school committee with a request to sell or give the Shaw pasture on Central Street for the site of a school to replace the Center School held in a room in the Town Hall, a location undesirable especially because of the danger to children at the crossroads. The location of the Shaw pasture proved to be undesirable.

When the old Hallock house burned, Mrs. Hudson bought the land and deeded it to her daughter Clara, who in turn later deeded it to the town. After learning from the “Town’s Fathers” that public opinion would favor the town’s accepting and maintaining a school and library building on this site, if funds could be obtained from private sources, Mrs. and Miss Hudson began the work of soliciting money for this cause. After her mother’s death in 1921, Miss Hudson continued the raising of all funds.

The final result was about $22,000 -of which Mrs. Ethel Hallock dupont, a descendant of Reverend Moses Hallock, gave $10,000 for the two rooms of the Hallock Memorial School. The Shaw descendants raised $5,000 for the Shaw Memorial Library, in memory of Mrs. Hudson’s father, Dr. Samuel Shaw, Plainfield’s first physician, and a graduate of Parson Hallock’s school. Seven thousand dollars in gifts of varying size from $5 up, including $1,000 from the town of Plainfield, were contributed by many donors. The school building committee consisted o£ Reverend George E. AIlen, who gave long and untiring service as chairman, Mr. Ezra P. Billings, and Mr. Bertram S. Longley. The architect was Mr. Karl S. Putnam of Northampton, the contractor Mr. E. C. Connelly. The building was dedicated September 26, 1925. At this time the library had increased to 6,000 volumes. The furnishings of the library (copies of early American) were given by Mrs. Hudson’s two children, Darwin Show Hudson and Clara Elizabeth Hudson, in memory of their mother.“

“As I write this during the summer of 1962, the Plainfield Public Library is prospering in a simple white building in the center of the town, a building which also houses Plainfield’s two-room consolidated school. It has had a succession of loyal librarians, and the present one, Mrs. Arvilla Dyer, has for some years promoted the reading of good books by children. Besides the regular Saturday afternoon library hours, the library has been open on a weekday afternoon long enough for the school children, excused grade by grade by their teachers, to withdraw the books they could read in a week. The books are taken back to their desks and then home in the school bus. In earlier years their books had often to be carried on foot to and from the library on Saturdays. In 1960 the circulation of this town of 244 people was over 12,000, or close to a book a week for every man, woman and child in the community. Mrs. Dyer gave this service without charge one afternoon a week.“