Well, That’s One Fine Kettle…!

Shaw Hudson House

Broom Street

North Street

As you drive around town here in Plainfield you may have noticed one of the above large black kettles displayed in folks’ yards, or you may even have one in your own yard, and wondered what are they and what were they used for? Pots for making soap? Antique bath tubs? A cooking vessel? Witch’s caldrons? The answer is none of the above. They are potash kettles! And Plainfield, as well as the entire New England region, has a rich history surrounding these kettles. As a matter of fact, they played a major role in both the economic and ecological history of early America. Who knew? As always, we find that one artifact can lead us to wonderful and important discoveries about our history. This is certainly the case with these kettles, so let’s learn about potash and the potash industry in our region. As always, any of the blue highlighted text are hyperlinks that will take you to more information.

First off, just what is a potash kettle and how was it used? We were lucky to have an expert in this field of study visit us in 2008 and help us uncover the mystery behind these kettles. Ralmon Jon Black (1939 – 2018), a noted historian from Williamsburg, Massachusetts, was quite familiar with these kettles, having published a booklet on Colonial Asheries and numerous research papers on the topic, including Potash and Asheries: The First and Most Profitable Industry and The Industrial Revolution Comes to the Hilltowns. He graciously offered his expertise and extensive research on our kettles and the history of how they were used, that led us on a another historical adventure.

To understand how the potash kettle was used one first has to understand what potash is. Potash, basically, is a term that comes from an early production technique where potassium was leached from wood ashes and concentrated by evaporating the leachate in large iron pots (“pot-ash”). That’s where our kettles come in! Potash refers to potassium compounds and potassium-bearing materials, most commonly potassium carbonate. The word “potash” originates from the Middle-Dutch “potaschen“, denoting “pot ashes”. Potash is considered to be the first industrial chemical and is an essential element for all plant, animal and human life.

Historically, potash was an important element in the manufacture of alum, saltpeter, soap, glass, tanned leather, gunpowder, paper, bleached cotton textiles, and various woolen goods. In the 18th century potash became an essential ingredient in the rising textile industry. It would also be used as a leavening agent in baking. Its most common use today is as fertilizer, potassium being one of the three crucial nutrients for plant growth (nitrogen and phosphorus are the others).

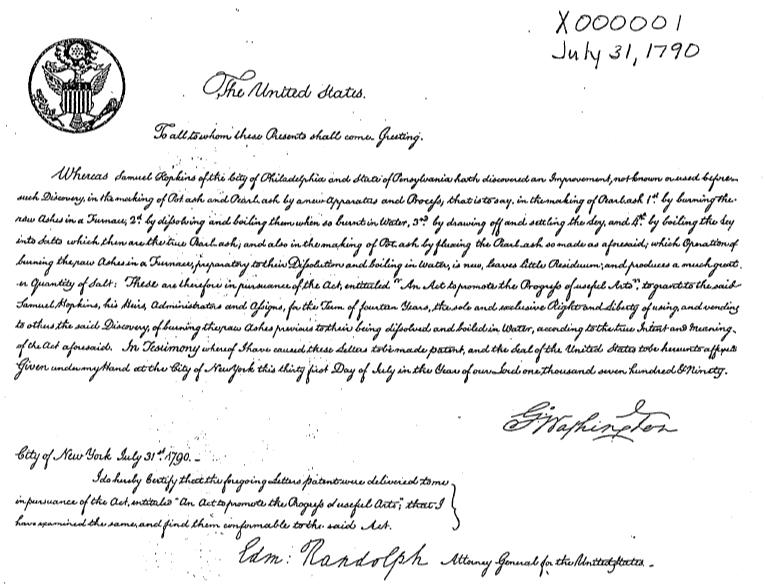

The America Colonies first entered the potash scene one year after members of the London Company founded Jamestown in 1608. Great Britain, and for that matter, much of Europe, had depleted most of their forests by this time and since potassium was in high demand, fueling what would soon become the Industrial Revolution, they looked to the rich forests of New England to meet these demands. Potash production soon became a very lucrative industry for cash strapped colonists. The first U.S. patent of any kind, Patent X000001 was granted on July 31, 1790 to Samuel Hopkins for an improvement “in the making of Pot ash and Pearl ash by a new Apparatus and Process”

“In the 18th century England imported potash from the American colonies and Russia. The best yields came from “elm, ash, sugar maple, hickory, beech, and basswood” trees that grew well in New England and southern Canada and west to Minnesota. But in New England by the end of the 18th century “farmers and householders were down to cooking and heating ashes…Moreover to assure [their] firewood supply, one-fifth of the typical farm had to be kept wooded. People began to try to extract more salts from these ashes and even to obtain potash from previously discarded waste ash. The potash industry was in crisis. Enter Samuel Hopkins.” Hopkins’s patented process called for furnace burning raw ashes and reburning the residues. As new hardwood lands were opened and as village asheries using the Hopkins methods under license began to replace processing by individual farmers, “the United States remained the world’s leading producer of potash,” until the 1860s, after which mined deposits in Europe made Germany the leader.” – Potash in Early Western New York by Robert G. Koch

When the colonists first settled in New England one thing they found in abundance was trees – particularly broadleaf hardwoods. These trees were both a blessing and a curse for the early settlers. They had to be removed before settlers could farm the land, an arduous task done with oxen teams and backbreaking labor. Many of the trees were used to build houses, many of them still standing today in Plainfield. Timber was also used for heating their homes, making charcoal, and for cooking. But the colonists soon realized that these trees could also become an important “cash crop” in ashes, and soon a thriving potash industry swept the Colonies, either importing their wood ashes to Great Britain and beyond, or making their own potash, using the potash kettles we see today around Plainfield.

Black writes in his essay, Potash and Asheries, “The earliest industry of the first settlers seemed so commonplace to them, as they had gone about it that it was to receive very short shrift if mentioned at all in any letters or memoirs. It was a dirty, exhausting farm chore that everyone engaged in out of sheer necessity, almost desperation. Their earliest endeavor was to clear the land and build a log home, then clear more land to sustain the agrarian lives they would lead. Sawmills were soon established to replace the strenuous manual operation and provide sawn lumber for frame houses. But the one prevalent activity eighteenth-century Williamsburge, which has received scant mention in all accounts, was the agricultural industry, producing ash, an industry complimentary to clearing farmland and lumbering. It was probably big at first but gradually waned over a period of time as the woods were depleted. No one could afford not to be involved: ashes had cash value and were so much an asset, no landowner could ignore the resource.”

The hardwood forests in the northeast were the best producers of potash because they contained a higher percentage of natural salts than trees found in other regions of the world. Giant elms were the most highly prized, now gone due to Dutch Elm disease, followed by oak, beech and ironwood. People could sell their fireplace ashes, and ashes from burning trees to clear the land, to the ashery for cash. The hilltowns were dotted with these asheries, with ashes supplied by most hilltown families. At the height of the potash industry a bushel of dry ash varied in price from 25 cents to 75 cents, depending on the quality. This became a “cash crop” for families to help make ends meet. It took 450 to 500 bushels of hardwood ash to make a ton of potash. The greatest potash productivity was in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. Yet, little of this industry has made it into the history books, but thanks to diligent research by historians, like Ralmon Jon Black, and others, who have have helped to “unearthed” this forgotten history, we are gaining a whole new appreciation for ashes.

Black’s interest in potash started as many historical research projects begin – having his curiosity sparked by the environment and artifacts that surrounded him. He begins his essay, Potash and Asheries by asking, “I had always wondered why the woodlands of Williamsburg had been so thoroughly cleared. It was amazing to me – why?” This lead him to years of researching, exploring, reaching out to other historians and local residents, and over time he came to the conclusion that indeed, it was the potash industry that played a major role in the deforestation of the region.

Black, in his article Colonial Asheries in the Valley, writes, “In 1760, conditions had ripened to the extent that New England colonies began breaking out of their palisades to occupy the uncharted wilderness. As the Hilltowns were being settled, potash was an important farm and home industry. It was a standing cash crop, money for the taking, when there was none other. It was worth silver in the foreign markets, where the textile industry desired tons and tons of it to make the scouring and bleaching agents they needed. This huge market trickled into the pockets of the common man, silver that would capitalize building the towns, roads, bridges, meetinghouses, schools, sawmills and gristmills.

Every one of these new settlers became engaged in some phase of the colonial potash business even if only to save the ashes from the fireplace to pay their taxes. Some husbandmen processed their ashes, leeching lye from them and evaporating it to black salts. Some grew their industry of taking potassium carbonate from their hardwood forest and the forests of their neighbors, refining it into pearlash in a kiln ready for export to England and France. There were entrepreneurial storekeepers accepting ashes in payment for their goods, and operating an ashery in conjunction with their stores. They were taking cartloads of commodities to more remote villages and trading them for ashes when there was no money. Potash receipts passed current when there was no other specie.(money) Many young men of the second generation struck out on their own, moving west before 1800, to carry on the only lucrative industry they had learned from their fathers, potash. Successive generations continued the harvest westward, making a great swath of the hardwoods, through Ohio and all the way to Michigan. It was a dangerous, dirty and an entirely unpleasant business, which ended when all the land had been cleared. It has gone unrecorded, as though it could not soon enough be forgotten. The relics of the potash industry are few, here the mysterious stoned up structure of a filled in potash cellar, there a leech stone with a circular groove cut into it, or a potash kettle which came to serve in evaporating maple sap, making soap, scalding hogs at slaughter or as a watering tank for the livestock. And everywhere, in every town, a “Potash Hill” a “Potash Brook” or “Potash Road.” The extent and magnitude of the colonial potash industry affected the economy of those times and the land forever, yet a social memory of it has been smudged by Forgetfulness and Time.

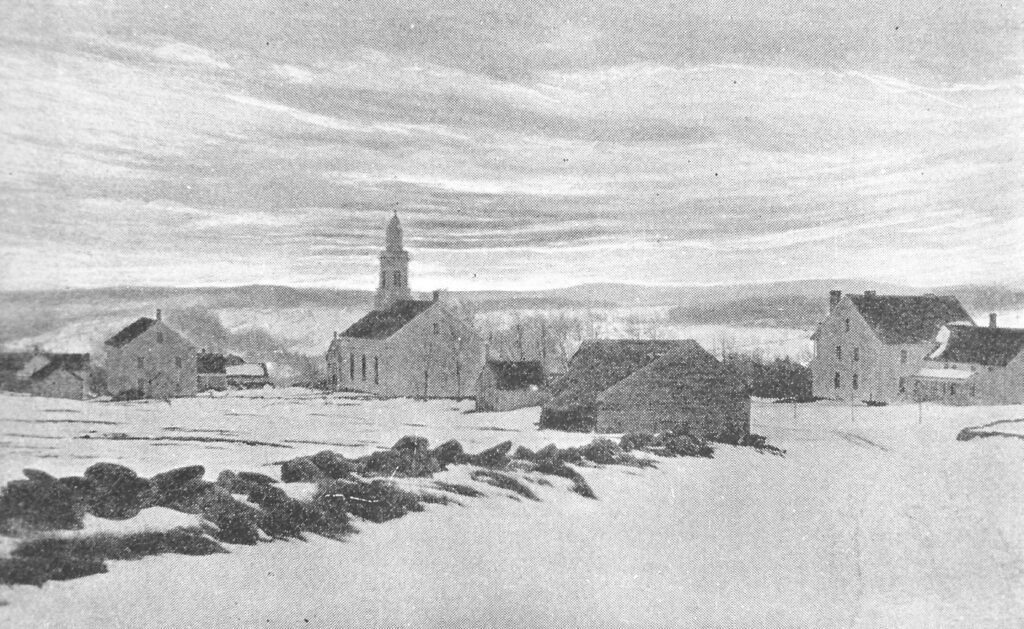

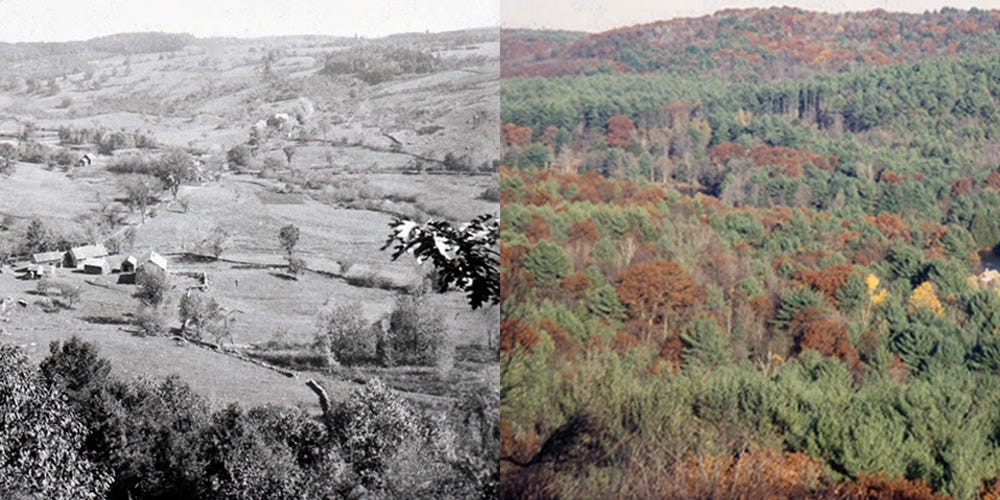

This view from ca. 1890, shows how Plainfield Center and the surrounding hills was deforested. From Clifton Johnson’s book, ‘Country Clouds and Sunshine

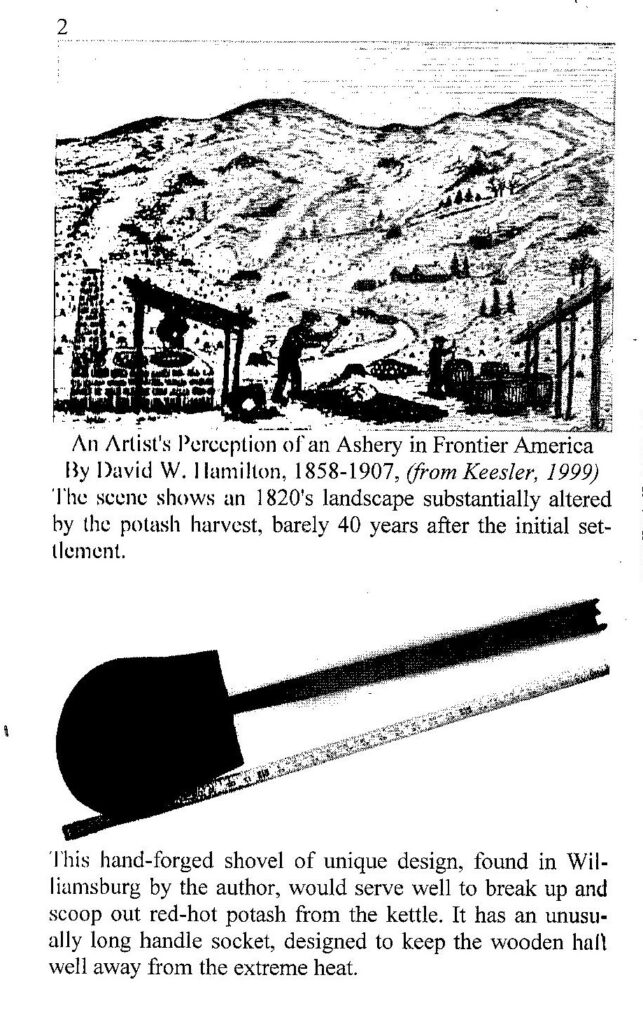

Black goes on to write – “About the time most of the easily accessible woodland had been burned and exported as potash, the textile industry, came riding the wave of the industrial revolution, and surfed upriver to the Hilltowns, with a renewed demand for potash. Farmers went further into the forest to produce ashes, sparing only the pine and hemlock, which bore little potash. Photographs made between 1860 and 1900 show a landscape so devoid of trees as to be unrecognizable in today’s eyes.

The changes in the land from 1750 to 1850—all the woodlands gone, the habitat for fauna and flora so altered, farms, roads, and mill villages built largely with the change the yeomen had made from potash. Yet somehow potash, as important an activity as it was, never survived in the collective memory of area. It was a resource, at first completely exhausted, then, just when it was starting to renew itself, science replaced it with totally unrelated sources, worldwide evaporate deposits and the sea itself.”

Harvard Forest Archive/David Foster

So how were our kettles actually used? Black describes the process as follows, “Besides the necessary ashes, leach and evaporator, the most critical element of the ashery was the expensive, heavy, bulky, thick-walled potash-kettle, capable of withstanding intense heat. About an inch thick and forty to sixty inches in diameter, with a capacity of 60 to 90 gallons, it was cast from 400 to 1,00 pounds of iron. An intense charcoal fire under the kettle, not only boiled down the lye, leaving a dark, crude crystalline residue of black salts, but by shoveling in more charcoal onto the fire, and maybe using bellows, the kettle was heated until the salts were melted into a liquid, red and glowing, burning off organic impurities and leaving a pink and gray colored alkali known as potash… Once cooled, the product, potash or pearlash was tightly packed into heavy oaken barrels and sealed to prevent drawing moisture from the air. On wagons or sleds these were borne away to market, bound for local textile mills or shipped off to Great Britain or France. “

Where might these potash kettle have been forged? Well, we know that Gilbert Richards had an iron foundry in Cummington in the mid-19th century so perhaps one, if not all of Plainfield’s potash kettles were forged locally.

Lye was produced by soaking ashes in hot water, filtering out the ashes, and repeating with fresh ashes as necessary to obtain the desired alkalinity in the resulting liquid. This liquid, commonly called lye could then be mixed with fats to produce soft soap, or it could be evaporated (often by boiling) to produce pot ash or black salts which still contained dark carbon impurities. The potash could then be baked in a kiln to further refine the substance into a pearly white material called pearl ash, pearl-ash or pearlash. The lye and potash stages were commonly performed on site by the settlers themselves, and the asheries only performed the final step and most difficult step of converting the black salts to pearlash.

While we currently have no indication that there were any asheries here in Plainfield, we do know, thanks to the deligent work of Mr. Black, that there were many in the region, including one behind the Brassworks in Haydenville, one at the present day Brewmaster’s Tavern in Williamsburg, and one off of Potash Brook in Goshen, just to name a few.

William Streeter from Cummington, shared the following notes with Mr. Black, “From 1790 to 1850 – a 60 year period – a large amount of potash was manufactured in Cummington. In that era the primary use for potash was in the making of soap. We wonder what the market for the Cummington potash production was. Some may have been shipped out of town to be sold, or it all may have been used locally.” “The historical span of the potash industry in Cummington,” Streeter goes on, “coincides closely with that of the textile industry in Cummington. Textile mills of this era produced woolen goods, cotton and satinet. Large amounts of soap, made with potash, were needed for scouring the wool, and bleaching and dyeing other types of cloth. It is the author’s[Streeter] theory that these requirements were met by the local potash industry. The Cummington account books show many entries for the sale or barter of ash[es]. At this time we have identified seven different potash operations and potash-burning pits off the north side of Potash Hill Road.”

So who knows? Perhaps one day we may discover some of Plainfield’s own potash operations. The search continues!

If you would like to purchase a copy of Ralmon Jon Black’s book, Colonial Asheries, which has much more about local ashieries and their relationship to American history at large, please send $12.00 ($10 + postage & packaging) to Williamsburg Historical Society, PO Box 233, Williamsburg MA 01096.

For more information on the potash industry click on any of the links below:

Colonial Asheries in the Valley by Ralmon Jon Black

Pearl Ash, Potash and Ashery by Kristin Holt

An Introduction to the Kirtland Flats Ashery by Benjamin C. Pykles

From Desperation to Deliverance, From Ashes to Cash by Varick Chittenden

Ash to Cash – The Untold Story Nature’s Burnt Offering to 19th Century Settlers by Georges Létourneau and Jay Sames

Potash in Early Western New York by Robert G. Koch

The First US Patent Was for Potash, But What the Hell Is Potash? by Michael Byrne

The Adverts 250 Project – Potash – Early American advertisements on potash