Identifying 18th and 19th Century Artifacts in the Plainfield Historical Society’s Collections: A Presentation by Dennis Picard

Each August, the Plainfield Historical Society (PHS) hosts a historian to discuss a different aspect of our town’s rich history. For 2020 we were fortunate to have Dennis D. Picard, a well known historian of all things western Massachusetts. Dennis has worked with the PHS in the past, helping us to identify many of the artifacts that we hold in our collections. He visited the barn at the Shaw Hudson House, where we hold many of our pieces, and pulled out a few items of interest to research and discuss at our meeting. As always, Dennis amaze us with his breath of knowledge and ability to make history “come alive”. He describes himself as, “An interpreter of a life that is foreign to us today and each of these unique items tell us all a story of our history.” Here is a little more on Mr. Picard.

Dennis has been a museum professional in the living history field for forty years. He began his career at Old Sturbridge Village in Sturbridge Massachusetts, in 1978, where he eventually spent twelve years filling various positions including lead interpreter, researching and designing many public programs which are still offered by that institution today. He also served on the staff of Hancock Shaker Village as a historic trade craftsman and site interpreter. Dennis is the recipient of various grants that allowed him to serve as project coordinator for research and implementation of programs and events at several historic sites and museums.

Dennis, with his background and museum experience, has authored many articles on the lifestyles and folkways of New England and has also served as a consultant for many Historical Societies and Museums. He has edited film scripts and reviewed historic novels for accuracy of content.

He has held the position of Assistant Director and Director at several sites including Fort Number Four in Charlestown New Hampshire, the Sheffield Historical Society in the Massachusetts Berkshires and has recently retired after 27 years at Storrowton Village Museum in West Springfield Massachusetts. He is also on the Board of Directors of the Pioneer Valley History Network and a member of the editorial board of the “Country School Journal.”- Westfield State Website

Let’s take a look at some of the items that Dennis picked out of our collections to share.

Bread Maker

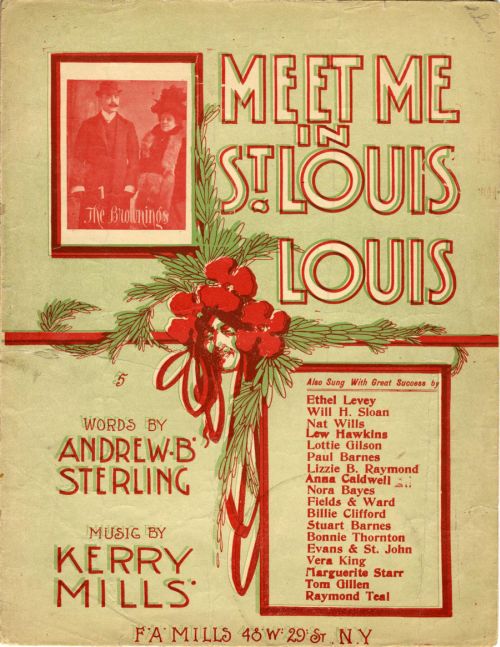

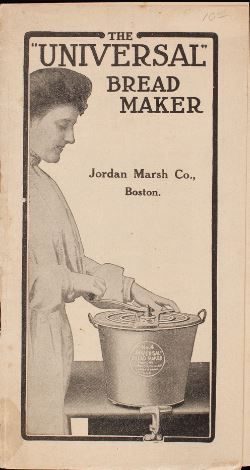

As Dennis introduced himself and before introducing the first artifact for discovery he played the classic song, Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis, better known as just “Meet Me in St. Louis”, a popular song from 1904 which celebrated the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, also known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. “What the heck does that have to do with Plainfield?”, he asked the crowd of about thirty-five, and then held up a metal bucket with a crank handle on it. He went on to explain that this item was the Universal Bread Maker that received the gold metal award at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Although it seems hard to believe now, this item was displayed as the latest in technology, the “wiz-bang tool of the era.” Dennis went on to explain that the bucket has a clamp that attaches to any table or counter, ingredients such as yeast, water, sugar, milk and flour goes in the bucket, the dough hook and top are placed on and then you crank for approximately three minutes, let it rise, crank again and voila! The proofing of the yeast and kneading of the dough and rising all were done in this machine, saving on time, energy, and the need for multiple bowls! Depending on the recipe the dough was removed, divided into two to four loaves and baked.

As a side note, the company, Landers, Frary & Clark, that originally patented and manufactured this bread machine, because of their experience and expertise in metal work, became one of the main providers of canteens and mess kits for American soldiers during World War I.

This machine is still made today, although now it is made of aluminum and not the iron and steel of the one in our collection. Because of Covid-19, many people have turned to baking their own bread again, partly because of shortages of ingredients and to save money, but more importantly, as a way to reconnect to the familiar in a time of chaos. Bread is one of the very foundations of human civilization. And baking brings a host of psychological benefits. It’s a productive form of self-expression and communication, a form of mindfulness, and a healthy distraction. In a word, baking can be a tremendous source of stress relief. If you would like to try one of the recipes included in the original bread maker check out the links below.

Instructions for Universal Bread Maker

National Museum of American History

The Universal Three Minute Bread Maker (1900)

Read more about the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition here.

Bark Spud

The next item Dennis chose to interpret was what is known as a spud. He was inspired to research this item because work had just been completed on the “summer kitchen” of the Shaw Hudson House and while renovating this structure many old tool marks were discovered. These marks can help to date old structures and we were pleased to have had some of these tool in our collection, perhaps the exact tools used in the original construction of the house.

Also called a peeling iron, the bark spud is one of our rediscovered logging tools. Curved along its length and coming to a bevel edge, the spud peels bark from a log while limiting damage to the wood underneath. Although crude in appearance, it’s remarkably efficient, especially if the tree was felled in the summer when the cambial layer is weakest.

Broad Axe

The next item up for interpretation was a broad axe. A broad axe is a large-(broad) headed axe. There are two categories of cutting edge on broadaxes, both are used for shaping logs by hewing. On one type, one side is flat and the other side beveled, a basilled edge, also called a side axe, single bevel, or chisle-edged axe. On the other type, both sides are beveled, sometimes called a double bevel axe, which produces a scalloped cut. On the basilled broadaxe the handle may curve away from the flat side to allow an optimal stance by the hewer in relation to the hewn surface. The flat blade is to make the flat surface but can only be worked from one direction and are right-handed or left-handed. The double bevel axe has a straight handle can be swung with either side against the wood. A double beveled broad axe can be used for chopping or notching and hewing. When used for hewing, a notch is chopped in the side of the log down to a marked line, called scoring. The pieces of wood between these notches are removed with an axe called joggling and then the remaining wood is chopped away to the line. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broadaxe)

To learn more about axes click on the links below.

An Axe to Grind: A Practical Ax Manual

Logs to Lumber: Hand-Hewn Timber the Old Way

How Adze, Axe, or Saw Cut Marks on Lumber Indicate Building Age & Wood Cutting Methods

Adz

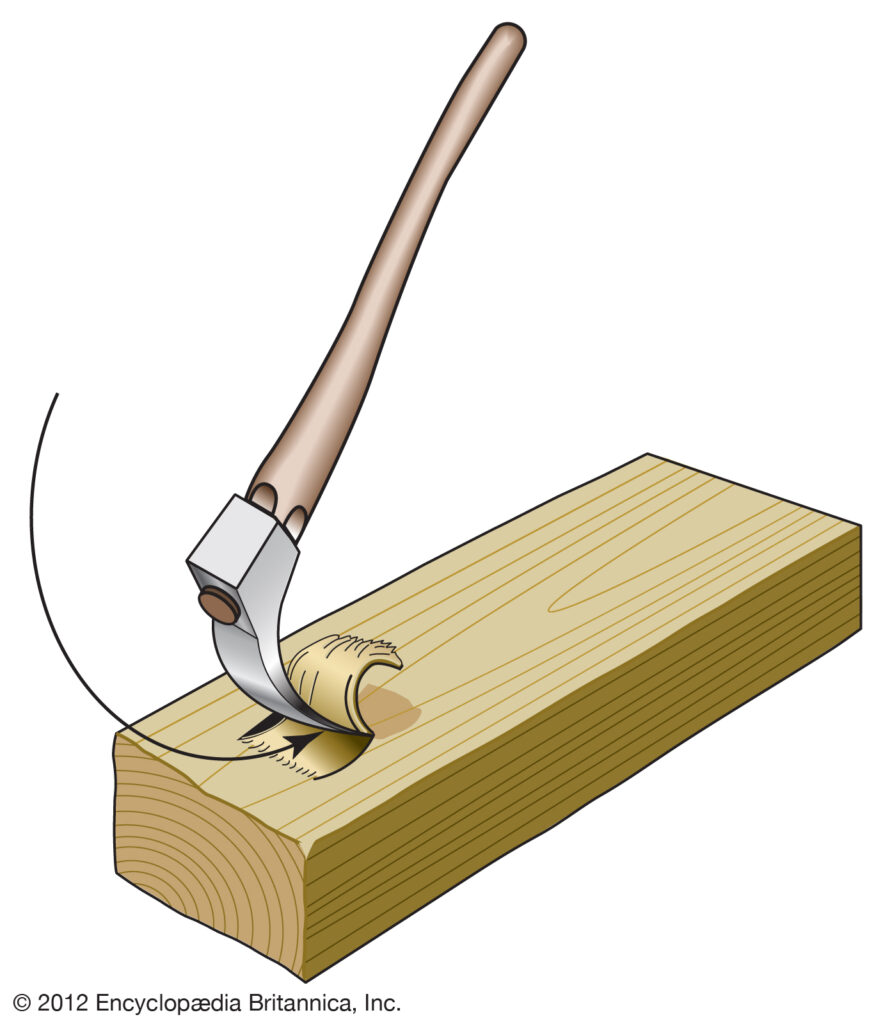

Continuing with the the theme of tools that may have been used when constructing the Shaw Hudson House, and many other homes in Plainfield in the 18th and 19th centuries, Dennis chose was what is referred to as an adz or adze. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, adz, also spelled adze, is a hand tool for shaping wood. One of the earliest tools, it was widely distributed in Stone Age cultures in the form of a handheld stone chipped to form a blade. By Egyptian times it had acquired a wooden haft, or handle, with a copper or bronze blade set flat at the top of the haft to form a T. In this form the adz continued to be the prime hand tool for shaping and trimming wood. A log or other piece of timber was laid on the ground or floor, and the carpenter stood astride or on it, swinging the adz in a pick-like action down and toward himself.

The Adze Tool: History, Safety, and Technique

To learn more about how to identify homes from tool marks click here.

Dennis was one of six people who, using many of the above tools, actually built the replication of the Saw mill at Old Sturbridge Village.

Mills and the Environment in New England

Grinding Stone

A grindstone is a round sharpening stone used for grinding or sharpening ferrous or iron tools. Grindstones are usually made from sandstone. Grindstone machines usually have pedals for speeding up and slowing down the stone to control the sharpening process. The earliest known representation of a rotary grindstone, operated by a crank handle, is found in the Carolingian manuscript known as the Utrecht Psalter. This pen drawing from about 830 goes back to a late antique original. The Luttrell Psalter, dating to around 1340, describes a grindstone rotated by two cranks, one at each end of its axle. Around 1480, the early medieval rotary grindstone was improved with a treadle and crank mechanism. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grindstone)

What’s the origin of the phrase, “Keep your nose to the grindstone” you might ask. To keep your nose to the grindstone is to apply yourself conscientiously to your work.

There are two rival explanations as to the origin of this phrase. One is that it comes from the supposed habit of millers who checked that the stones used for grinding cereal weren’t overheating by putting their nose to the stone in order to smell any burning. The other is that it comes from the practice of knife grinders when sharpening blades to bend over the stone, or even to lie flat on their fronts, with their faces near the grindstone in order to hold the blades against the stone.

The miller’s tale might have worked for Chaucer, but it doesn’t help here.

All the evidence is against the miller’s tale. Firstly, the stones used by millers were commonly called millstones, not grindstones. The two terms were sometimes interchanged but the distinction between the two was made at least as early as 1400, when this line was printed in Turnament Totenham: “Ther was gryndulstones in gravy, And mylstones in mawmany.”

The Middle English language there is difficult to interpret but it certainly shows the grindstones and millstones as being distinct from each other. If the derivation was from milling we would expect the phrase to be ‘nose to the millstone’.

A second point in favour of the tool sharpening derivation is that all the early citations refer to holding someone’s nose to the grindstone as a form of punishment. This is more in keeping with the notion of the continuous hard labour implicit in being strapped to one’s bench than it is to the occasional sniffing of ground flour by a miller.

The first known citation is John Frith’s A mirrour or glasse to know thyselfe, 1532: “This Text holdeth their noses so hard to the grindstone, that it clean disfigureth their faces.”

The phrase appears in print at various dates since the 16th century. It was well-enough known in rural USA in the early 20th century for this picture, which alludes to the ‘holding someone’s nose to the grindstone’ version of the phrase, to have been staged as a joke (circa 1910). (https://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/keep-your-nose-to-the-grindstone.html)

Snow Shovel

As Plainfield residents, we are all familiar with the snow shovel but who knew there was a history behind them? Well of course, Dennis!

To learn more about the Blizzard of 1888 click on the links below.

The Great Blizzard Of 1888 Was So Devastating That We’re Still Feeling Its Effects Today

National Museum of American History: The Blizzard of 1888

We were pleased to have members of the Beals family attend this presentation. They were in town to tour their ancestor’s mill site and to learn more about a presentation bucket they have had in the family for generations. To learn more about the PHS’s Mill River Site click here and to learn about the Beals’ bucket click here.

This program was made available through a generous grant from the Plainfield Cultural Council and the Massachusetts Cultural Council.