The Country Kitchen

The kitchen of the Shaw-Hudson house, complete with many of the artifacts used in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, surely makes one appreciate the modern conveniences we now have. Let’s see how life in this kitchen was like through Clara Hudson’s eyes.

The following are excerpts from The Romances of a Country Doctor, a paper read at the annual meeting of the Northampton Historical Society at the Unitarian Church, Northampton, on October 7, 1947 and Plain Tales from Plainfield or The Way Things Used to Be, 1962, both by Clara Elizabeth Hudson. Ms. Hudson was a granddaughter of Dr. Samuel Shaw and the last surviving relative to live in the Shaw Hudson House.

Click on photographs to see a larger image. All blue text is hyperlinked to pages with more information.

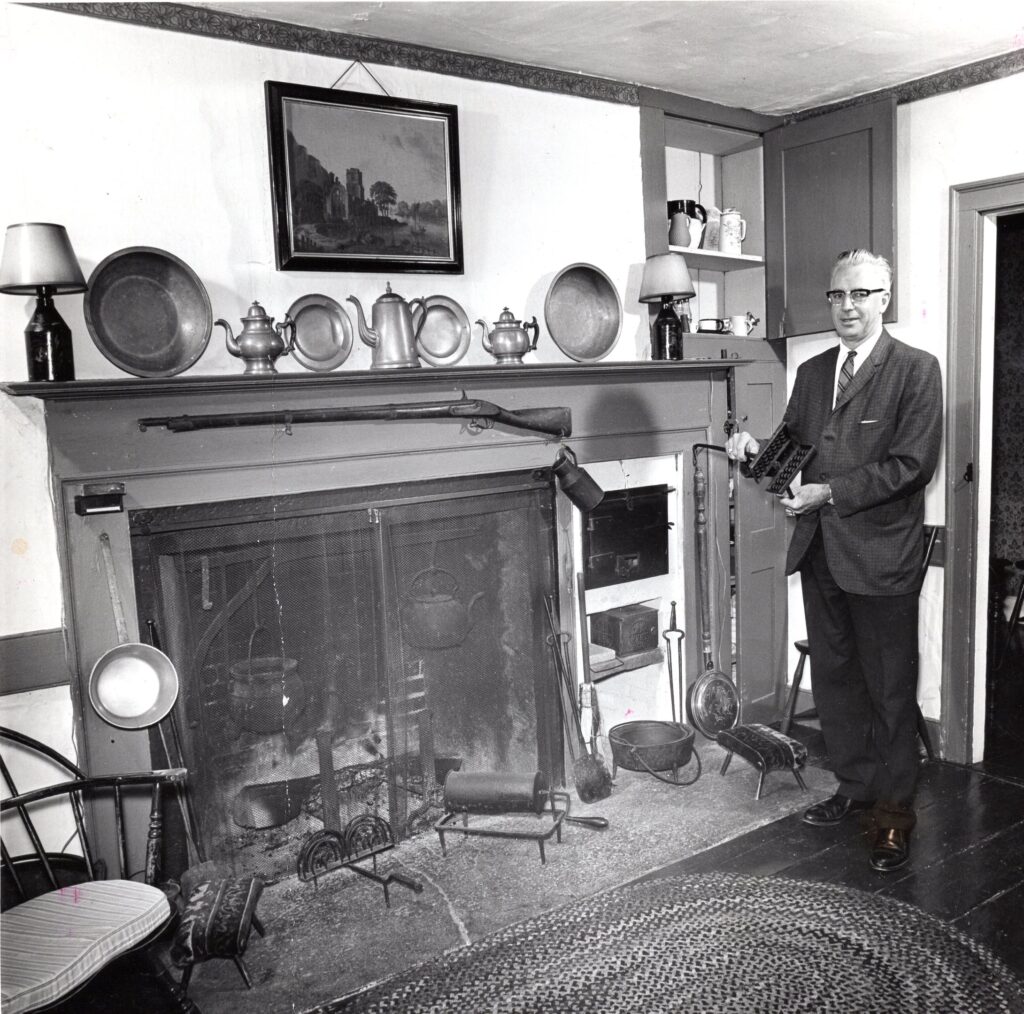

“Our old kitchen was a most interesting room. Above the large fireplace was a mantel on which were various articles of pewter, as well as a small clock which was wound daily with a key. Suspended horizontally below the mantel was the family musket, which was supposed to be so placed that the barrel pointed to the door thorough which an enemy was most likely to attack. In later years a fireboard closed off the use of the fireplace and an iron cook stove was used for cooking and heating. This was the arrangement during my childhood and until some time in the 1930’s. Electric current was brought to some twenty centrally located Plainfield homes sometime in the 1920’s, at which time kerosene lamps were replaced by electricity. Filling the lamps with kerosene, polishing lamp chimneys and trimming wicks had been one of my chores, and I was delighted to be rid of those jobs. For reading, student lamps had yielded a very soft shaded light; much better than the light from unshaded lamps.

In some country kitchens I remember seeing a mirror on the wall and under it a small shelf for a comb and brush. This was so that before meals one’s hair could be made presentable, and the kitchen was the most comfortable and easiest place in which to tidy up. Most bedrooms with their bowls and pitchers of cold water were unheated and bathrooms were rare. Hands and faces were usually washed at the backroom sink. In summer one ate in the dining room, in winter in the kitchen. In my day the hour for Supper was often adjusted to permit my mother and myself to go outdoors to see Plainfield’s glorious sunsets.

Grandmother Shaw baked bread in the brick oven; first the interior was heated by a fire of wood, usually maple or birch. The brick interior was already warm from its proximity to the large fireplace, in which a fire was kept going much of the time, maple, birch and beech being ordinarily used as fuel. When the hot ashes were taken out on an iron spade called a “peel,” they were often deposited to cool in .an open depression of the stone or brick foundation in the wall just below the brick oven. The brick oven was brushed out with an eagle’s wing or birch twigs. Our brick oven had an iron-hinged door with a small draft-opening in it.

In the early days there were no tin pans. Cabbage leaves were laid on the floor of the hot oven. Then a wooden peel was sprinkled with com meal to keep the loaves of bread placed on it from sticking. After inserting the peel part way into the oven, a quick jerk caused the loaf to slip off onto the cabbage leaves.

Adjoining the kitchen was a one-room ell known as the “backroom.” Here much of the kitchen work was done at the large soapstone sink, which had a drain ending under the back lawn. Adjoining the sink was the water barrel with fresh water running continuously in and out. Cucumbers were sometimes kept cool by floating in the water. For drinking, one caught the water direct from the pipe in a tin dipper. At intervals we used to pull a long plug out of a hole in the bottom of the barrel and scrub the bottom and sides with a clean broom. For dishwashing big pans were set in the sink. Hot water from the iron teakettle on the stove in the kitchen or from the stove’s reservoir was available.

The ell had no cellar underneath and in the late autumn I remember once that the floor was so cold I wore my arctics and stood on a thick mat while I washed dishes. Wooden utensils such as mixing spoons, the ‘potato`smasher”, etc., were kept in a drawer of the big wooden table.

The windowless pot-closet under the back stairs, called “the Black Hole of Calcutta,” held such articles as three-legged pots for fireplace use, a long-bandied waffle iron, and a long-handled wire-mesh container in which one popped corn.

The farther end of the back-room usually held several cords of neatly piled wood, and in the “Glory Hole” at the top of the back stairs were kept the family trunks and other seldom used and bulky paraphernalia. In a small, brown, hair covered trunk was stored the large United States flag, beautifully made by my two aunts. It was displayed on all appropriate occasions.

Often my thoughts go back to the coffee which in my younger days we had at home in Plainfield. My family always sent to Park and Tilford in New York City for its coffee ~ Mocha and Java, ordered green in the bean. On arrival in Plainfield the antique coffee roaster was produced from “The black hole of Calcutta” and a sizable amount of the coffee put in through an opening in the hinged cover. Removing a lid of the wood-burning stove, one inserted the roaster into the hole, which it fitted exactly. I was usually the one delegated to turn the handle round and round, which made the mixer inside keep the coffee from burning over the hot coals. When sufficiently roasted, the coffee was packed in airtight containers. Each morning the first sound I heard was usually that of the day’s measure of coffee beans being ground by my Aunt Stella in the old coffee mill on the pantry wall. Never since have I tasted such coffee, made from freshly ground beans and water freshly caught, boiling in a thoroughly scrubbed pot. And the aroma almost surpassed the taste.“

Ms. Hudson refers to the ell off the back of the kitchen as the “back kitchen” or “summer kitchen.” As the large fireplaces in most early kitchens gave off a lot of heat, many families had another kitchen to work in during the hot summer months. To learn more about these summer kitchens check out What to Expect When You Hear the Words “Summer Kitchen”

The gun hanging over the kitchen fireplace was made by Lemuel Pomeroy, a famous western Massachusetts gunsmith. Pomeroy prospered, particularly in the three decades, beginning in 1816, during which he produced muskets for the federal government. The manufacturer employed 30 gunsmiths in his shop. A typical musket was marked “L Pomeroy” over “Pittsfield,” just as this gun is marked.

To learn more about the development of the modern day kitchen, visit A Brief History of the Kitchen