Blanche Svoboda Cizek: Memories of a Life Well-Lived

by Rebecca Williams Mlynarczyk, March 2019

Long-time Plainfield resident Blanche Cizek passed away on September 5, 2021, at the age of 102. Affectionately known as “Plainfield’s Sweetheart,” Blanche was beloved by her many friends. We hope this piece, based on oral history interviews, will add to your appreciation of Blanche’s life and legacy.

It’s hard to believe that my good friend Blanche Cizek is about to turn 100. Nearly twelve years ago I began a project focused on what I then called “successful aging.” Contemplating retirement myself, I wanted to interview elderly women I admired for their “vital engagement with living in the present.” From the beginning, Blanche was on my short list.* Like myself, she was a New Yorker who started coming to Plainfield with her husband as a weekend retreat from their busy lives in the city. In retirement, they moved to Plainfield full time. She was a very positive force in the community, a leader in town organizations, and a gifted musician, who often played the piano and led the choir when the church music director wasn’t available. But more important for my project on aging, I admired Blanche as a woman of warmth and wisdom with a delightful sense of humor. When I first interviewed her in 2007, it was hard to believe that this vital, engaged woman was in her late eighties. I wanted to know the secrets of her success.

On a warm, sunny day in the summer of 2007, I pulled into the circular driveway at Blanche’s house on South Central Street for our first interview. It had been hard to schedule this meeting because she had so many other social engagements. But she managed to fit me in for a couple of hours on the morning of July 6.

Blanche welcomed me into her beautiful home. I told her that I was interested in learning how she and the other women I was interviewing had adjusted to a time of life that many found challenging, how they managed to live such rewarding lives in the years after eighty. But, I told Blanche, in planning for the interviews I realized that I couldn’t start with questions about the present, that I really needed to start with people’s childhoods. I had a feeling that how people cope with aging goes back to their childhood.

And so we began. Reading over the transcripts of my interviews with Blanche from 2007 (she was eighty-eight at the time), I’m struck by how much of what we talked about relates to immigration. Her family’s history, like that of so many American families over the centuries, could be entitled “An Immigrant Success Story.”

Both of Blanche’s parents arrived in New York City in 1904, having come here by boat from Bohemia in what is now called the Czech Republic. They were teenagers, sixteen or seventeen years old at the time, and were sponsored by relatives who had immigrated earlier. Blanche’s mother was one of nine children. The oldest son and the youngest son stayed in Europe as did the parents. All the others came to America during the big immigration period around the turn of the century.

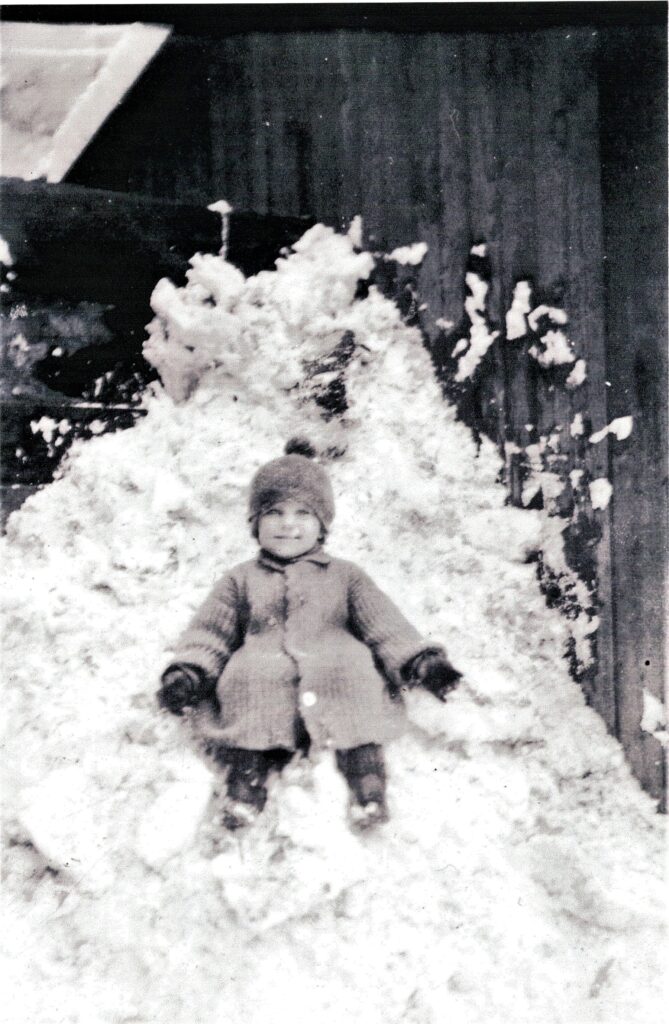

Blanche’s parents started their new life in this country on East 78th Street between First and York Avenues in Manhattan. Blanche Svoboda (a common Czech name, meaning “freedom”) was born there on March 10, 1919. Her older brother, Stanley, had been born six years earlier.

Her father became a barber, a skill he acquired here. He eventually owned his own shop, which, according to Blanche, “turned out to be a lucrative business.” Blanche has many fond memories of the hours she spent in this shop.

“It fascinated me [spoken with emphasis] when I was a little girl because it had all these beautiful mirrors and these wonderfully colored bottles of pomade. And these sterilizers with the towels. And there were times when I spent time in the shop. I remember men sitting in these barber chairs, and my father shaving them with a straight razor and putting these sterilized towels on. And, of course, I observed all these things. Everything was so sparkling, and there was my father—he was very tall and slender—and here he was in this white jacket. And everything was very sanitary and ‘tonsorial,’ I think is the word.”

We both laughed as we pictured the young Blanche quietly observing all the details of this male sanctum. When I asked her to say more about her father, she replied:

“My father was a strict disciplinarian, so my brother and I just obeyed everything. I won’t say I was a meek child. But I was a very obedient child. And we were not of very affluent means. We were comfortable. We were clean. And it often surprises me. We lived on the East Side in New York, in a tenement actually. But my parents were so meticulously clean. Everybody was. The neighborhood was just spotless.”

Blanche remembers that there was a horse stable just across the street from their apartment, but the street was always clean. Any mess from the horses was picked up immediately.

When I asked Blanche what her mother was like, she smiled.

“My mother was very social minded. When immigrants came to this country, as you know, they settled in ethnic communities. East 78th was a little bit above the Czech community, which was more in the 60s and the lower 70s. We were actually near the German neighborhood, which was in the 80s. Mama got involved in this amateur theater group. They put on these wonderful, wonderful performances, plays in Czech, all in Czech. And Mama just loved the stage [spoken with emphasis]. She had a wonderful alto voice; she sang beautifully. Later on both my mother and my father became members of a big choir, and they went to different parts of the city to perform. My father had a fine bass voice. So maybe that’s where my love of music came from.”

Blanche’s parents made sure that both of their children studied a musical instrument. Her brother took violin lessons, and Blanche began piano lessons at the age of eight. She recalls, “At that time, I think we paid a dollar a lesson, and the lesson was about an hour.” Blanche was a diligent and talented pupil, and she continued lessons with this first teacher for the next ten years. She remembers him as a very important mentor.

“He was a Moravian, so the dialect was a little different. And believe it or not, all my instructions were in Czech. He was a sweet man. Now when I think back, he reminded me of Schubert. In the kind of glasses he wore. And just his kind of attitude. He was the sweetest man [spoken with emphasis]. I just loved him.”

Soon Blanche’s elementary school teachers learned that she could play the piano, and she was asked to help out at school assemblies.

“P.S. 127 had sliding doors in the classrooms, and those doors were slid back, and that became a big space, and all the classes were able to be in one room. What did I play? ‘America’ and ‘My Country ’Tis of Thee.’ I always played the anthem for the assembly. And then later on—of course, we didn’t have middle school—so we went to the ninth grade, and our graduation performance was H.M.S. Pinafore. Of course, a condensed version. And, of course, who did all the accompanying but me?”

When I mentioned that this must have been challenging since it’s really like accompanying an opera, Blanche replied, in her unassuming way, “Well, I guess I had a particular God-given talent. I didn’t have any formal musical education. I just took piano lessons.”

Another vivid memory Blanche recalls from her childhood occurred one night when she was walking with her mother in Manhattan, returning home from one of the Czech theater performances. There was a movie theater on First Avenue around 76th Street called the Merle Theater. Blanche explained that as she looked down the street,

“I saw people standing around. And being a child I thought, ‘I think I’ll go and take a look and see what that is.’ And there I saw this man standing in this big feather thing—an Indian in costume—and with a wagon on the street, pulled by horses. And he was talking about all this curative stuff—all these bottles of things that would cure arthritis and rheumatism and any kind of a problem that you had. And I just stood there with my mouth wide open—fascinated, watching this performance. And I saw people buying it. Of course, I didn’t have that kind of money. We children were lucky if we had a penny for penny candy. Do you remember ice cream parlors in Manhattan? If Mama took me for an ice cream soda, that was special. Not like kids today who have ice cream and soda all the time. But I remember that show so vividly because it seemed so strange to me.”

Later in our interview I asked Blanche to say a bit more about her parents—their parenting style and the values she learned from them.

“Well, to be honest, we learned to be thrifty because they were difficult years during the Depression. I heard, in the course of conversation, that my parents had all their money in a bank called the Bank of Europe in New York. And then one day my father came home and said, ‘President Roosevelt closed all the banks,’ I thought, ‘Oh, my goodness. What is going to happen with all of this?’ But there were no serious repercussions for our family. We never seemed to have a problem like a lot of people did during the Depression.”

In talking about her parents’ relationship, Blanche repeated that her father was a strict disciplinarian. She went on to explain, “As was usually the custom, the man was the head of the household, and the wife was as obedient as the children.” But her mother had many friends, especially in her community theater group, and this provided an important bond between her parents.

“There were friends who were involved in these performances. And my father also directed these plays, so that there was a mutual feeling of togetherness there. I remember coming from a home where there was love and there was no friction. We always knew we were loved, so we never had any psychological problems that so many of the young people have today.”

Blanche feels that part of her parents’ strength and resilience was related to being immigrants: “Everything was left behind. They didn’t know the language. This is what happened to immigrants. And yet I think it gives you that character that so often you need later in life.”

When the family was having money troubles, Blanche’s mother had to take whatever job was available. It was because of one of these jobs that Blanche used to think of her mother as Carmen, the star of Bizet’s opera.

“I always think of my mother in reference to the work that she was doing. The young people in Carmen worked in this cigar factory, and, lo and behold, this is what my mother did. There must have been a cigar factory—again, in hearsay—I think it was in the 90s, and Mama worked in this cigar factory rolling the wrappers for this Cuban tobacco. I said, ‘Papa, when did you start smoking cigars?’ And he said, ‘Oh, I started when I was about twelve years old when I was in Europe.’ And while she was working in the cigar factory, Mama, of course, had the opportunity to bring back rejects, so my father had this wonderful supply of cigars. But it’s funny that I always think of my mother as Carmen—though she certainly didn’t look like a Spanish girl dancing around. But that was what she did for quite a long time.”

Her father too had to work very long hours in his barber shop, six days a week and even on Sunday mornings. “But,” Blanche said, “I never heard my mother or my father complain about working hard. These older generations were used to working harder. This was their way of life.”

In 1929, when Blanche was nine years old, the family was affluent enough to buy a home of their own in the suburbs—East Elmhurst, Queens. It was the beginning of the Depression, and many homes were in foreclosure. Several of Blanche’s aunts bought homes there around this time, and her parents decided to do the same. For Blanche the move marked the beginning of a new era in her childhood.

“It was wonderful because we each had our own bedroom, and we could do what we wanted. At that time, the neighborhood wasn’t that populated, and so there were what we used to call lots. You know houses would eventually be built, but at that time they were empty. And I remember going with my cousins, and we would play in these lots. It was a wonderful free time. You didn’t have any fear of anything bad happening. There were no drugs. And people, young people, especially children, respected the police. They respected their teachers, and the whole discipline thing was so different from what it is now. I’m not saying that all young people today are bad. That is not what I intend to put across. But I had an essentially happy childhood.”

When Blanche was thirteen, her parents had another baby, her brother Allen. She became very close to her younger brother, explaining that she “had already started having those maternal instincts when he was born.” Her mother was involved in a lot of arts activities in Manhattan. If she had an evening rehearsal, Blanche would stay home to care for the baby. “I gave him his bath, I gave him his supper, and I put him to bed. I just had a good part of his upbringing.” These early bonds were important, and Blanche and Allen remained very close as adults.

Later in the interview, as we continued to talk about the years in Queens, I asked how she would compare her life as a child to the lives of children today. She paused and then replied:

“Well, I think we were more free in respect to not having to worry about drugs and alcohol. While children today have much more in material things than we ever did, I think perhaps on the whole maybe we were happier children than many children are today. I don’t know. It may not be in every circumstance of course. Also there was very little traffic on the streets. My father bought a car. He was very good about anything new on the market. I remember he built a television set when televisions were in their infancy. I think perhaps if Papa had had more, I think his potential was greater than what he achieved, and I have a feeling that later on in life, it was a little frustrating for him. Some of us don’t realize our potential. We can do many more things than we actually do.”

As a young girl, Blanche did not have every material advantage, but she took active steps to achieve her potential. She had heard that the high schools in her part of Queens were not very strong. She did some research and learned that Julia Richman High School on 67th Street in Manhattan had a good reputation. “It was an all girls school, and that rather appealed to me, so I went there.” She added, “I did hear that they had a big swimming pool, and I thought that was an enticement.” We both laughed at this “confession.” Blanche was very pleased with this decision. Every day for four years, she took the subway to school (the fare was five cents), where she took the commercial course.

As she has done throughout her life, Blanche made friends in high school. “I didn’t have a lot of friends, but the friends I made were very special.” The school was integrated, and Blanche mentioned that one of her friends was a black girl named Marjorie Lee. “She was the sweetest girl you could ever imagine. She wasn’t catty at all. We never saw each other outside of school, but there was a kinship there.”

During her high school years, Blanche continued to progress in her piano studies. In her teens she performed with a group of amateurs at the Sokol Hall, a Czech center for the arts and physical fitness located on East 71st Street in Manhattan.* Twice she was asked to be a soloist. She remembered playing the Rachmaninoff in C sharp minor and a Chopin etude. I asked if she suffered from stage fright at these public performances, and she said, “Of course, there is a certain amount of nervousness before. But once I get into doing what I have to do, then I’m very comfortable.” Playing the piano has remained a source of great satisfaction throughout Blanche’s life, even into her eighties and nineties. She told me:

“You know when I’m kind of stressed out or tired and I just need a little bit of respite, I say, ‘Oh, the heck with whatever I’m doing’ And I go to the piano, and I will just sit down, and before I know it, two hours have gone. My mind is so concentrated on what I am doing. And it is really such a relaxing way of getting rid of all the stress.”

I asked Blanche if she attended college, and she quickly replied. “No, no, no. I graduated high school in 1936. That was the height of the Depression. Unfortunately, my father became quite ill, and Mama had to go back to work. Just one of those things. I would have loved to pursue a musical education but . . . .”

We had talked for nearly two hours, but the time had flown by. I was captivated by these views of a New York City I had never known and this glimpse of a young woman looking toward the future and eager to shape her life in the years to come.

* * *

About two weeks later I interviewed Blanche again. Walking up to the door, I admired this lovely country home nestled at the side of the road. A beautiful, big catalpa tree marked the entrance to the driveway. The red clapboards shone in the sunlight, and the lawn was neatly trimmed.

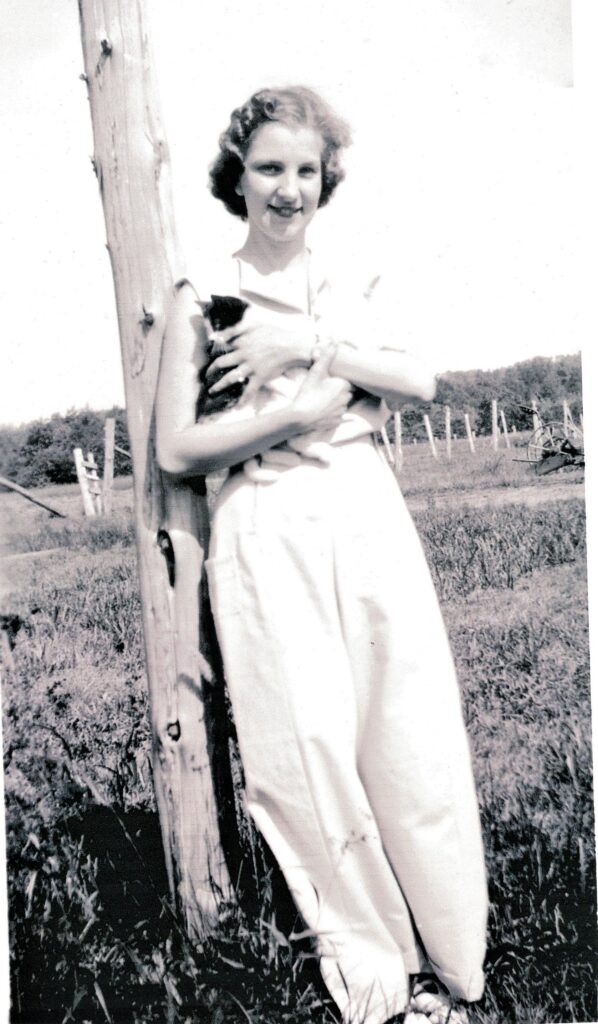

As I entered through the side door, Blanche welcomed me with a warm smile. We decided to sit in the den, a wood-paneled room at the back of the house with a sliding-glass door opening onto the deck and the woodland beyond. Blanche spends a lot of her time in this room looking out into the woods. On this morning she described a scene she had recently seen through the window. “There was this mama deer with its baby, and I thought if I only had a camera. It was so pretty. I just wish I could’ve put it on my mind and just left it there.” Blanche’s life is enriched by her closeness to the natural world and her love of animals. In the summer of 2007, she also had a little black cat, Cleo (short for Cleopatra). From time to time I would hear the jingling of the bell around Cleo’s neck, and she would jump up on my lap for a minute as if she wanted to be included in the conversation.

In this second interview, we focused on Blanche’s life after high school—her work, her marriage, her children, and eventually the move to Plainfield and her life there. We started with the story of how she met her husband, Al Cizek, also the child of Czech immigrants. As it turned out, she met Al when she was on a date with another boy.

“You know in those days [the mid-1930s] we went to tea dances, and we went to formal dances, and this one time we went to what was called The Architectural Ball—believe it or not at the Waldorf Astoria. My date had a car, and he said to me, ‘Now we have to pick up another couple because he has no car, and we will go together.’ Who did it turn out to be but Al?”

Clearly there was an attraction between Blanche and Al, “a spark,” as she called it. But Al didn’t call her for a couple of months. Years later, after they’d been married a long time, she asked him why he had waited so long to call her. “And he said, ‘Well, you know, I didn’t want you to think I was too interested in you!’ And I said, ‘That’s silly!” But Al, who was six years older than Blanche, was not one to move too quickly on an issue as important as marriage.

He had graduated from New York University with an engineering degree in 1935; Blanche graduated from high school in 1936. Finally, on Blanche’s birthday, March 10, 1939, Al proposed, and they got married in September of 1940. “It was a loooong [emphasizing the word “long”] engagement. For whatever reason, I have no idea. I don’t know.”

One event that Blanche recalls from the first summer of their engagement was a sailing trip Al took up Long Island Sound with his father and a friend. Al was an excellent sailor and the proud owner of a 32-foot sloop, which he used to sail out of City Island. She pointed to a photo. “There’s a picture of Al with his sailor’s cap and the boat in the background. I think it had a 40-foot mast.” While Al was out with his friend and his father, they encountered a storm. Later, Al described this storm in a long letter to Blanche. She explained, “Of course, in those days neither one of us had telephones. I still have his old letters upstairs.” I noted that after Blanche said this, she “giggled like a girl.” Clearly these letters from Al are among her most treasured possessions.

Blanche explained that later, after they were married, she spent many days on the boat. She would leave Long Island early in the morning, “and I’d hop on the bus and the subway and go out to City Island and stay out for the whole day. I’d come back as red as a cherry tomato, all sunburned. But it was a wonderful experience. I loved the boat too.”

Whenever Blanche talks about her husband, her voice changes, and you can tell that theirs was a wonderful marriage.

“I consider myself blessed because Al was a wonderful man. When I got married, I must have been the most naïve bride on the face of this earth. I mean, whatever my husband said, that was what was supposed to be done. Not that I didn’t have any leeway. Al gave me all the freedom I needed after we were married. But that was just the way I was brought up. And I really do consider myself very blessed that I had a faithful and a loving husband.”

This statement implies that Blanche usually deferred to her husband about decisions they made early in the marriage. But one thing that impresses me about Blanche is the way that, throughout her adult life, she takes control in planning for the future just as, during her teen years, she sought out an excellent high school for herself even if it meant daily subway rides from Queens to Manhattan. For the first few years, Blanche and Al lived in the upstairs apartment of her parents’ house in East Elmhurst. But even in the early days of their marriage, Blanche had a plan for the future.

“I worked in a payroll office after we were married. At that time there were no computers. But I remember this very, very large adding machine, a huge thing compared to these little bits of things that people use now. And I kind of set a plan that fortunately worked out. I said, ‘I’ll work two years, and then I’ll take a two-year hiatus to do my own thing, and then we can start having a family, buy a house, or whatever.’ I quit my job in 1942, and Richard was born in 1944. And we moved into our own home in Valley Stream, Long Island, in 1949.”

In talking about their early life together, Blanche focused quite a bit on Al’s career as an engineer, taking great pride in his resourcefulness and accomplishments. During their engagement, he worked for American Radiator in Mount Vernon, New York, but one day he telephoned Blanche and told her:

“’Honey, I’m out of a job.’ He had been laid off that day. I said, ‘Well, what are you going to do?’ And he said, ‘I’m just going to apply to every place I can.’ Al was one of those people who didn’t let anything get by him. He had a handle on everything, and he took advantage of every opportunity.”

Eventually, he took a job with Richmond Screw Anchor and then with Babcox and Wilcox. About a month after their marriage in September 1940, while Al was on a business trip to Cincinnati, he received a telegram at home, and Blanche opened it. She called Al long distance and read the telegram to him. It said, “Please report immediately in reference to a job at the Bureau of Ships at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.”

Even though Al was happy in his current position, he decided he really had no choice but to accept this job working for the government. This was 1940, and war was imminent. Al stayed in this job for thirty years until his retirement, and both of them were pleased with this decision. Not only did Al play an important role in the war effort, working six days a week with overtime if necessary, but his job also earned him a deferment for the duration. Blanche expressed relief that neither her husband nor her sons, who were college students during the Vietnam War, ever had to go to war. “I just thank the Lord, every time, that none of them had to be in the service.”

After the end of World War II, Blanche faced a test of her own courage and determination. She had suffered from scoliosis since childhood, but despite doing all the stretching exercises prescribed by the New York Orthopedic Hospital, the condition was getting worse. Al’s brother was a physician, having graduated from Columbia Physicians and Surgeons in 1941. When Blanche told him about her worsening symptoms, he sent her to a respected orthopedic surgeon, who told her he could do a bone fusion that would straighten out the bottom of the spine though not the top. Without surgery, the condition was likely to progress, perhaps eventually leaving her crippled. As she has done throughout her life, Blanche faced this decision with realism and optimism. Even though she was the mother of a four-year-old child at this time, she decided to go ahead and have the operation.

“I went in for surgery in 1948, and I was hospitalized for three months. It was rough. Now they use some kind of a metal rod, a stainless steel rod. But at that time they took my shin bone, and put it on the spine, and fused it. I have about a foot-long fusion on my spine. That was May, and I got out in the middle of August. I was in a body cast from my hips up to my armpits. I was on my stomach for ten weeks.”

As is typical for Blanche, rather than dwelling on the hardships, she saw the positive side of this very challenging experience.

“I was so blessed because I knew Richard was well taken care of [he spent most of this time with Al’s parents]. That was my primary concern. I was in University Hospital on 20th Street and Second Avenue in Manhattan. And every day after work [at the Navy Yard in Brooklyn] Al would come directly to the hospital to visit me, and then he would stop to see Richard at his parents’ house, and then he went home. But, you know, as I think back, I remember the first week when I had the cast on, I said, “I’m not gonna survive this.” I didn’t know how I could. I didn’t want to eat. I couldn’t. I was face down. My arms and my legs were not confined, so they said, “You’ve got to keep your arms and your legs moving.” So there I was trying to do whatever. But it took me about a week, and I started to eat. You know, you just survive. Somehow you get through it. Well, I was young, twenty-nine, I think.”

Because of the hospital rules at the time, young Richard wasn’t allowed to visit his mother during the whole three-month period. Sometimes they would bring him to look up at her window, but she couldn’t see him because of her position in bed. Finally, in August of 1948 she got wonderful news:

“I guess it was an intern who came in in the morning and said, ‘Well, guess what?’ I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘Your cast is coming off.’ I’d keep asking questions all the time because you never got a satisfactory answer. It was frightening because they used this little saw, and it was on my back. And I said, ‘What are you doing?’ And he said,’We have to cut along your spine so we can get the cast open.’ And I said, ‘Oh, please, be careful.’ As I think back, I must have sounded very silly. And when they took it off, I said, ‘Please scratch my back! I am so itchy.’ Then the nurse came in and said, ‘Mrs. Cizek, we’re going to let you dangle your legs.’ And I said, bravely, ‘Oh, you don’t have to hold me, I’ll be just fine.’ They just smiled and said, ‘Mm-hmm.’ So I went to put my feet down, and I couldn’t feel them.”

Of course, she couldn’t! Her feet hadn’t been on the floor for three months!

After being discharged from the hospital, Blanche had to wear a back brace for two years and special shoes. She was given careful instructions for the recovery period: “You can’t do any housecleaning, you can’t do this, you can’t do that. And I thought, I have a four-year-old child. So I just disregarded much of this advice.” Al decided that Blanche deserved a vacation after this long ordeal, so they picked up Richard and drove to New Hampshire, where they had spent their honeymoon. Blanche remembers how she felt leaving the hospital: “Ahh! I felt like I was living again. Just to get out.”

I asked Blanche if she felt the operation had been a success, and she said that it had. “Oh, I think I probably would have been crippled if I hadn’t had the surgery. I probably would have been wheelchair bound or not able to walk. You see now it’s starting to bother me again. But . . . .” Her voice trailed off. Blanche has never been one to focus on the difficulties of her life.

Back in 1948, her biggest question was when she could have another baby. The doctor’s answer was clear cut: “Don’t you even think about having a baby until I give you the go ahead!” So Blanche waited another five years. Albert, Jr., was born on May 1, 1953. Telling me about the birth of her second son, Blanche gave credit where credit was due: “Praise the Lord!”

Both boys were healthy and well adjusted. “I fortunately had two wonderful children. They never got into a lot of trouble, nothing that I can ever remember.” Both were good students and eventually attended Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, as their father had before them. All three of the Cizek men majored in mechanical engineering. Both sons eventually married and had children, all of them girls. Richard and his wife, Carol, have one daughter, Laura. Al, Jr., and Joan have two daughters, Emma and Ellen. Blanche jokes: “The Lord blessed me with two wonderful sons, and now he’s blessed me with five wonderful girls!” She also has two great-grandsons, Laura’s children, Colin and Aaron.

I asked Blanche to talk about what she and Al were like as parents, what values she tried to instill in her sons.

“We were, I think, very strict disciplinarians with our children. I remember when the boys went away to school, I said, ‘Now, boys, you make one mistake, and it’s going to stay with you. And if you make a big one, it will stay with you for the rest of your life, so be careful.’ And, as I say, they were basically good. I would say that we let them do what they wanted within the bounds of what they should be doing. And, of course, they knew that. They were brought up in our Valley Stream Presbyterian Church. And Al and I were very content when they went away to school. We felt assured that they would not get into a lot of trouble. And they didn’t.”

As Blanche talked about family life with her husband and the boys, I was captivated by the calm, peaceful, orderly existence she was describing. It was almost like watching old black and white TV shows from my own youth—Father Knows Best or Leave It to Beaver. For example, I loved the story about how Blanche learned to drive:

“We bought our first car in 1941, and then we got another one in 1948. That was right after the war, and cars were difficult to get. But Al had some kind of connection. Believe it or not, he went to Detroit and picked up the car there. It was a big Dodge, and it had Fluid Drive. And that’s what I learned to drive on. Al tried to teach me, but I ended up in tears. I said, ‘Don’t bear down on me like this.’”

Blanche laughed when she told me this story. Eventually her son Richard was old enough to take her out, and he’s the one who actually taught her to drive. She soon became a very competent driver, which had its advantages for her husband. Al took the Long Island Railroad to work, walking about a mile to the station. But once Blanche had learned to drive, he would often say:

“’Ooh, honey, would you want to drive me to the station in the morning?’ That was when I started taking him. I had a sweetheart of a husband. In the evenings he’d make his lunch, put it in the refrigerator. In the morning, when the boys were still in bed, he’d get up, go downstairs, and make his breakfast. When he was sitting down to eat breakfast, I would hear, ‘Honey [said very sweetly], time to get up.’ And then I would just put a coat on and drive him to the station and come back home. By then it was time for the boys to get up to go to school. I’d make them breakfast, stop at the bakery for fresh rolls or fresh buns. Except that one time I had a little bit of trouble with the car, and here I was in my pajamas with just a coat on. [We both laughed.] So after that I put a pair of slacks on.”

It makes me nostalgic to hear Blanche talk about these orderly routines of her family life in the 1950s and 1960s. Their life sounds so different from the frenetic, often chaotic lives of young families today.

I asked Blanche to talk about the changes she has seen in women’s lives during her lifetime. She mentioned that, of course, there are more mothers working now than ever before and said she hoped that conditions in the workplace for women have improved. Beyond that, she was hesitant to comment: “I was out of the mainstream for so many years, not having worked for all those years, so I don’t know if I could make an evaluation.”

Next I asked, “During those years, did you ever feel frustrated or that something was lacking in your life?” She sounded very sure responding to this question: “Never. Because the music kept me so occupied. And my church work. I went to Bible study. I went to fellowship. I did my programs. I went to the luncheons. I was literally on the go a good part of the time. And then having two houses to keep going.”*

I followed up: “So you weren’t one of those women that Betty Friedan talks about when she refers to ‘the problem that has no name.’ Women who were stuck at home in the suburbs.” Blanche was quick to respond: “No. And I don’t think anybody should have a problem like that unless they’re just so introverted that they . . . . I always loved to get out and meet people, and I think I could talk to people quite easily.” Even at age, eighty-eight (Blanche’s age at the time of this interview), she was still very good at getting out and meeting people, still driving to visit with friends and involved in many community groups in and around Plainfield.

Blanche and Al bought their house in Plainfield in 1957 as a second home and retreat from their busy lives in the city. When Al retired at age fifty-nine, they essentially rebuilt the house, putting on additions, and making sure everything was shipshape when the family moved to Plainfield full time. By this time their older son Richard was out of college; he had gotten married in 1969. Young Al was about to begin his studies at Stevens. Blanche described their new life in Plainfield:

“Al retired in 1971, and he died in 1999. Those were wonderful retirement years for him, and I really thank the Lord for that. He loved being up here. All the pressures were gone. He loved tinkering around. I guess that was the mechanical part of him. He loved to listen to good music. He was a big opera buff. He loved to read. So time was never heavy on his hands.”

The Cizeks soon became pillars of the Plainfield community. Both were active members of the Plainfield Congregational Church, where Blanche often played the piano. She also joined the nondenominational Ladies Benevolent Society (LBS), serving as president of this organization for seven years. Blanche described why she finally decided to step down from this big job:

“Well, you know, the LBS things have gotten more involved. And I don’t know too much about government grants and things that we can avail ourselves of right now. And everybody has a computer, which I don’t have. So it got to the point where I thought, ‘Well, I think I’ll let it go to the younger generation because they know how to handle these things better.’ And frankly I was getting a little bit weary. You know, enough is enough.”

One of the findings of research on positive aging is that it’s important to know when to let go of things that have been important in the past. And I’m convinced that this is one of the secrets of Blanche’s successful aging.

The hardest experience of letting go, however, was Al’s death from heart disease in 1999. She explained this most painful part of her life. “Al’s heart wasn’t working properly, and it made him weaker and weaker. He had his first serious attack three or four years before he died.” These were difficult years because their older son Richard was also having serious health struggles at the time, a kidney condition that was eventually successfully resolved. Al had gotten a pacemaker, which helped for a few years, but then his condition got worse.

“One night (it was a Thursday or a Friday), he was in bed, and he said, ‘Honey, I’m having terrible trouble breathing. You’d better call 911.’ And when he said that, I knew it was not good. I stayed in the hospital with him. I hadn’t brought any extra clothes, but I wouldn’t go home. And he died that following Monday.”

Blanche’s daughters-in-law were a source of strength during this time of loss. She told me:

“You know, I am so blessed with these girls. Joanie, who is Al’s wife, she really takes the bull by the horns. I was in the hospital and she said, ‘Blanche, have you had anything to eat?’ And I said, ‘Oh, yes, I’ve nibbled on things.’ And she brought me a whole tray of food.”

I was happy to hear this and said, “Nice. You’ve finally got your daughters. You do need support at a time like that. Not everybody’s lucky enough to get it. But everybody needs it.”

Blanche continued:

“I don’t know what I would have done without them. I remember it was snowing. It was in March, and the weather was bad. Al and Joanie drove me home, and they stayed here for two days. [pause] And took care of everything. Joanie took care of everything. You know, you’re so bewildered. It’s very difficult to know even what to do. My husband took care of everything. He took care of all the books, all the payments, everything. And I thought, ‘Oh, my goodness!’ Your mind just doesn’t work.’ [pause]”

Knowing Blanche as I do now, a woman who is so competent and in control of her own life, I said, “I’m wondering if you feel like the loss, after you lost him, whether you feel like it really changed you, your own identity. Any deep changes after that?” I’ll never forget her answer.

“Well, your whole life, when something like that happens, is a series of adjustments. Nothing seems to be the same. There are things you have to do with the house, with bookkeeping, even balancing the checking account, which I didn’t even do. I said to my daughter-in-law Carol, ‘What do I do here?’ I had kind of an idea what to do, but she said, ‘No, it’s very simple. Let’s do it this way.’ And I did.”

She paused and then continued speaking very slowly, choosing her words carefully but with a strong, I would say with an unshakeable confidence in what she was saying.

“But I was able to take Al’s death with a certain amount of, should I say calmness or whatever, because I know what the Lord has promised. And my faith tells me that God has prepared a place for us. I do believe in eternity. If you read Revelation, there is such a beautiful description of the new Jerusalem and what will happen. And there are no tears, there’s no more pain. And I was so assured of that that I think it was a good part of my being able to cope after Al died. Because the promises of the Lord are true, and they’re right, and we can depend on them. [pause]”

Blanche and I had been talking for nearly two hours in a conversation covering sixty-seven years of her life. Both of us were beginning to feel tired. In winding down, we shared our thoughts about the previous Sunday’s sermon at the Plainfield church. The guest minister had preached on the well-known passage from Ecclesiastes:

“To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under heaven.”

* * *

Everyone seems to agree that as we get older, time passes more quickly. It is hard for me to believe that twelve years have gone by since these two conversations with Blanche. In that time, I have gotten to know her even better, and she continues to be a source of inspiration to me. Now, as she approaches her one hundredth birthday, she still lives independently at her home on South Central Street though she now needs more help from devoted friends and neighbors. A few years ago, Helene Tamarin, a younger friend from town, began to do her grocery shopping and trash removal, and generally help out in many other ways.

Blanche, as always in control of her own life, decided at age ninety that it was time to stop driving. Throughout her nineties, however, she stayed very active as others were always volunteering to give her a ride. She attended regular meetings and activities of the Ladies Benevolent Society, went to church every Sunday and study group every Tuesday. Alice Schertle and Susan Pearson took her with them to screenings of Metropolitan Opera broadcasts at the Clark Art Museum in Williamstown, and she often attended summer concerts at the Plainfield Church.

At age ninety-nine, Blanche has begun to curtail her outside activities though she continues to have lots of contact with neighbors and friends. She uses the telephone to stay in touch, and the “supper club” meets at her house every Monday evening; Anna Hathaway, Thelma Pilgrim, and Nancy Benson come over to share a pot luck meal and watch Jeopardy together. And she has many other visitors. Some stop by to bring a meal or just chat for a while. I think I speak for others as well as myself when I say that a visit with Blanche has a way of just making a person feel better about living in this world.

How to explain the effect that Blanche has on the people who know and love her? It will always remain something of a mystery. But her genuine interest in other people, her faith in God, and her positive outlook for the future have played a role in her ability to make and keep friends—and perhaps even in her longevity. It turns out that the centenarians, a group she is about to join, are a pretty special breed. In a 2010 New York Times article about people who live to be a hundred, Jane Brody listed what she called “three critical attributes that might be dubbed longevity’s version of the three R’s: resolution, resourcefulness and resilience.”*

Anyone who knows Blanche would agree that she has all three of these qualities in spades. It was because of them that she was able to return home after having surgery in spring 2016 followed by several months of recuperation in the hospital. One Sunday in July 2017, after I drove her home from church, we sat in her living room, and she talked about how she deals with life’s ups and downs. “Life is a series of adjustments. As you get older it’s harder to deal with these changes, but what choice do we have? You can either be miserable all the time or choose to be happy.” Then she said, with strong emphasis: “It’s important to discipline your mind.”

Those of us who know and love Blanche as the ever-cheerful, optimistic person she is might be surprised to learn of the steely resolve that underlies this optimism. Her openness to change and her positive attitude are not just the result of a natural optimism but rather a conscious choice that requires great discipline. Because, as she also emphasized, “Life is a kick!” There are many times in life that Blanche has been on the receiving end of these kicks, but she always manages to get back up, accept what she cannot change, and move on. Toward the end of this conversation, she said,

“I think this is something I learned from my mother. In many ways, she had a difficult life, but she always stayed positive and managed to hold things together for our family. For example, after we had moved to Queens, my father had some financial problems, and my mother decided, ‘Look. We have this whole two-story house. We will just move into one half of the house and rent out the other half.’ No matter what the problem, my mother could always find a way to cope with it.”

Blanche Svoboda Cizek, like her mother before her, has not only coped. She has prospered, reaping the rewards of a long and fulfilling life. Happy Birthday, dear friend!

What a wonderful story of a life well lived

Blanche was truly remarkable

Thank you, Rebecca for recording the life of Blanche Cizek