Anne Laura Clarke 1788 – 1861

The Shaw-Hudson house contains many important pieces in its collections, but possible none as impressive as the works by Anne Laura Clarke, a teacher and lecturer of the early 19th century. While her needlework and theorem painting speak of the role women of this time period, one just need look a little closer to uncover the extraordinary life of this unconventional woman.

The following are excerpts from The Romances of a Country Doctor, a paper read at the annual meeting of the Northampton Historical Society at the Unitarian Church, Northampton, on October 7, 1947 and Plain Tales from Plainfield or The Way Things Used to Be, 1962, both by Clara Elizabeth Hudson. Ms. Hudson was a granddaughter of Dr. Samuel Shaw and the last surviving relative to live in the Shaw-Hudson House.

Click on photographs to enlarge and blue hyperlinks to learn more.

“To our Plainfield house was taken a wonderful picture, several feet long, done by Great-aunt Anne. [Anne Laura Clarke] It showed President Washington’s home in Mount Vernon, embroidered in silk in a wide variety of stitches and with the sky painted in water colors. Whether the sofa bedstead which stood beneath it belonged to her, I do not know. Two other pictures by her on white velvet were still lifes, mostly of fruit and flowers.

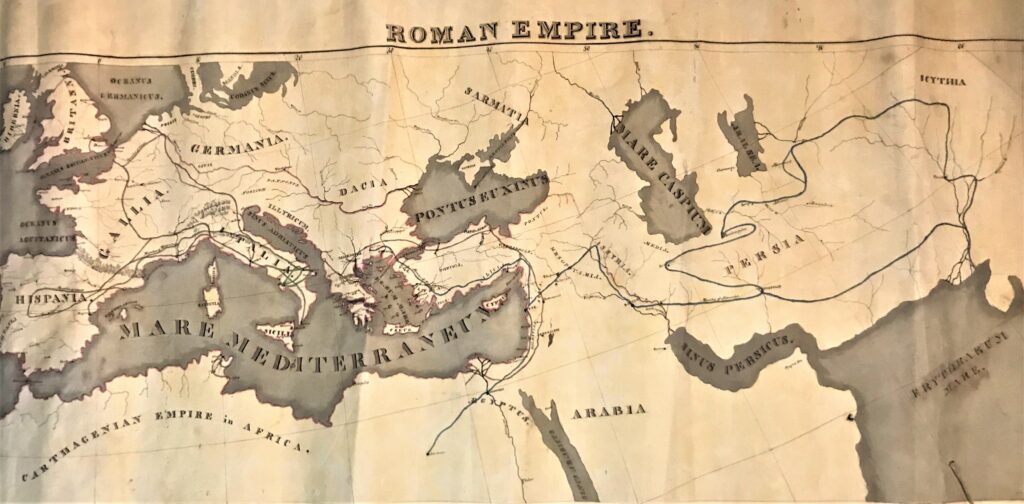

In the attic of our Plainfield house I found some years ago a box of hand-painted, copper-plated, magic-lantern slides. They were used by my Grandmother Shaw’s sister, Miss Anne Laura Clarke, daughter of Joseph Clarke, the adopted son of Major Joseph Hawley[III} of Northampton. Anne Laura Clarke was said to be the first woman historical lecturer ~ or “lecturess” – in the United States. Some of the slides were of the kings and queens of England, some of ancient and modem costumes; others were of astronomical diagrams and constellations, and views of buildings; and there were humorous slides, too. Several of the pictures were in each “slider,” which was pushed by hand through the magic lantern, the illumination furnished by a candle or by spermacetti in an argand lamp attached to a belt around the waist.

The first projection of a picture on a screen took place in 1645 in Rome, by a German Jesuit, Athanasius Kircher. The device was referred to as a “Magia Catoptrica.” My Great-aunt Anne’s magic lantern was known as a Phantasmagoria,” and in 1823 a pamphlet had been published describing the improved phantasmagoria lantern. No name of inventor, manufacturer, or editor is given in the pamphlet but the sliders were described in the accompanying booklet along with Miss Clarke’s notes on lecturing. She gave lectures in Boston and New York City, and as far west as Ohio, always wearing a bonnet, and in a day when skirts swept the ground wore her skirts “way ‘up to her ankles.” She was considered strong-minded and thought that women should vote.“

“Some years ago I gave the sliders and accompanying booklet to the Northampton Historical Society.

Some time in the first quarter of the twentieth century I received a present of a Bausch and Lomb “Balopticon” which was run by a tank of carbide gas. On one occasion I remember giving by request in the Plainfield Town Hall an illustrated lecture accompanied by a script of the Battle of Gettysburg. Now stereopticon lectures use electricity.

On May 1, 1810 Miss Clarke opened a school for girls on Pleasant Street in Northampton. It had been the custom to allow girls to attend the public schools in summer and in her school Miss Clarke followed this custom. The subjects taught were reading, writing,-I find no mention of arithmetic- geography, grammar, needlework (plain and fine), various kinds of embroidery, filigree, tambour, drawing and painting.

When, in 1825, Lafayette came to Northampton from Springfield, the procession marched up Pleasant Street. Judge Lyman’s wife sent flowers, which the girls of Miss Clarke’s school, grouped in front, strewed before the general. One of those girls was Miss Jennie Smith, who later lived in the Isaac Damon house (now the property of the Northampton Historical Society). One of my friends has remarked that it is a ‘`far cry” from rose leaves for Lafayette on Pleasant Street to ticker tape on Broadway. At the reception for Lafayette at the Warner House the ladies’ gloves bore pictures of Lafayette. When he kissed their hands he kissed his own picture.

Major Joseph Hawley, a man of distinguished standing in his day, was chosen as delegate to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1774. He was a melancholiac and refused to accept the appointment. John Adams was selected to go in his place. There ensued a correspondence between the two, and Mr. Adams’ letters to the Major were handed down to his adopted son, Joseph Clarke, and then to Mr. Clarke’s daughter, Anne. She gave them to George Bancroft, the historian, and he gave them to the Lenox Library in New York City. Later they passed on to the New York Public Library where they have been kept in a locked repository and where I have seen them. Great-aunt Anne kept one torn letter of John Adams in which he begs Major Hawley’s advice on various matters of importance as a very great favor. In turn, this letter came down to me. In 1962 I gave this letter to the New York Public Library and it proved to be the one missing letter in the correspondence between John Adams and Major Hawley desired by the editors of the forthcoming complete edition of the letters of John Adams.

Unfortunately, I know nothing of Great-aunt Anne’s later years. She died on August 15, 1861 and is buried in the Bridge Street Cemetery in Northampton.“

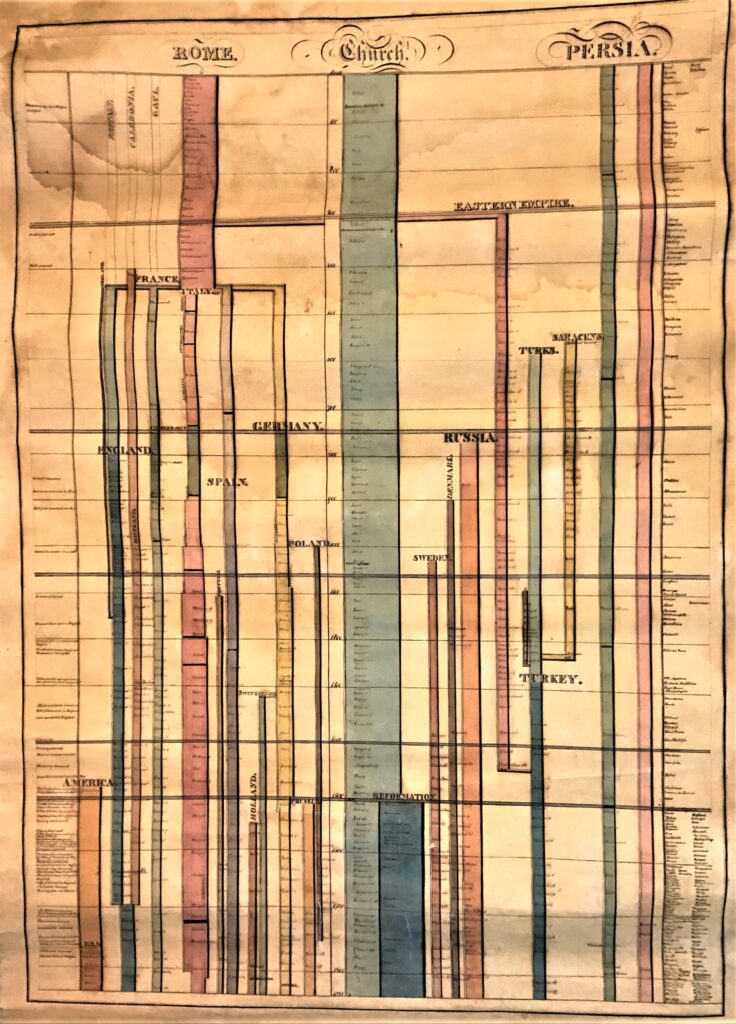

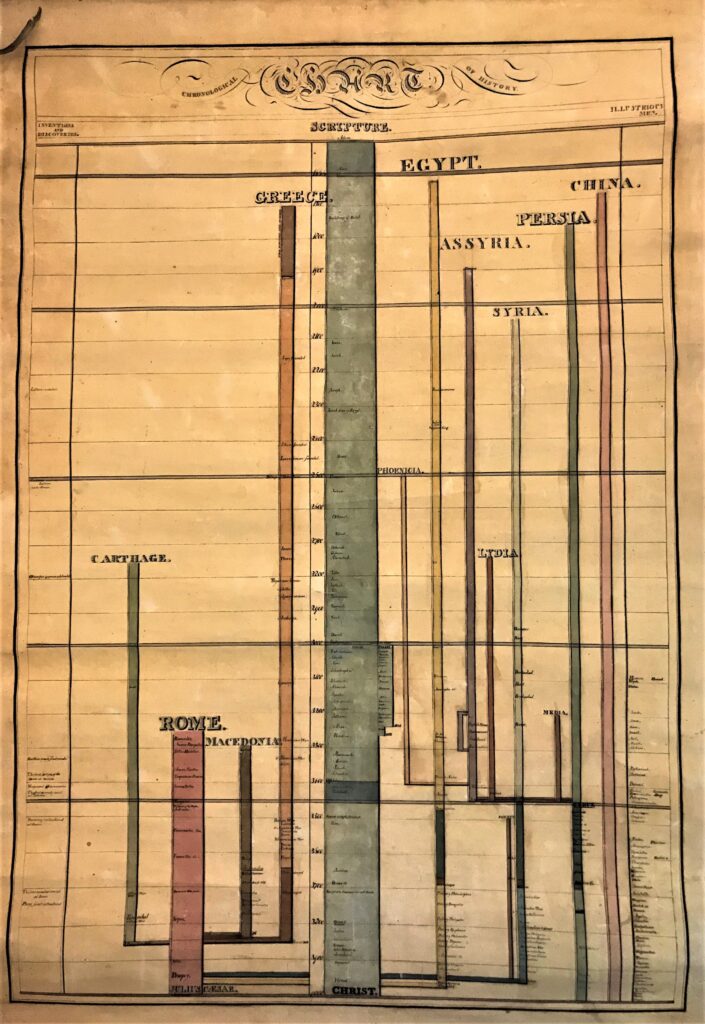

Tucked away in an old truck up in the attic of the Shaw-Hudson house were found a stack of old scrolls. Once unraveled – very carefully – the scrolls were found to be created by Anne Laura Clarke, used as visual aids for her historical lectures.

Granville Ganter, is his paper entitled Mistress of Her Art: Anne Laura Clarke, Traveling Lecturer of the 1820s writes of Anne Clarke’s teaching days, “Anne Laura Clarke, the eldest of six children, was born on 4 July 1788 in Northampton, Massachusetts. During her twenties, her father, Joseph O. Clarke Esq., became mired in the financial depression that developed toward the end of the War of 1812. Although her father’s family pedigree was not particularly distinguished – Joseph was the son of a saddle and harness maker—he ranked among Northampton’s elite because, as a boy, his intellectual abilities had recommended him to one of Northampton’s leading citizens, Major Joseph Hawley.

When Hawley died in 1788, some of his lands and all of his library were bequeathed to Joseph, whom he had informally adopted. Wealthy enough to afford a $110 church pew in 1812, the Clarkes were struggling by war’s end. Joseph wrote to his daughter in 1815 that many of the family’s friends were financially ruined—some as much as $27,000 in debt—and the Clarke family had begun taking in boarders to help pay expenses. Anne, twenty-seven years old, had accepted a teaching job 140 miles away at Fishkill Landing on the Hudson River, and in the spring of 1816, she was planning to move to New York City to study painting.

Although the family’s income continued to decline, Anne’s father, who had great faith in her potential as a visual artist, urged her to stay in Manhattan until she had become “a complete mistress of the art you practice.” He wrote that he would send whatever money he could spare toward that end.

In succeeding years, however, the money flowed in the opposite direction. Late in 1817, Anne made the bold step of accepting a teaching position in central Georgia, where she lived for two years while sending money home to help her recently widowed father pay back the loans and mortgages he had taken out on the family property. When she arrived in Georgia, Anne had her eleven-year-old sister Elizabeth in tow, and a year later her fifteen-year-old brother Frederick joined them, siblings Anne educated as well as supported.

After year-long teaching jobs in Sparta and Powelton, Anne moved to a teaching position in Petersburg, Virginia, where, according to a May 1822 letter, one of her paintings was chosen for exhibition at an academy.

As a general teacher in both Georgia and Virginia, Clarke earned an adequate income, which she supplemented by offering instruction in the ornamental subjects of French, music and drawing. Her income was approximately $800 a year in Sparta, $900 at Powelton, and $500 in Virginia. The terms of her employment were irregular, however, and she had additional room-and-board expenses for her siblings.

During most of this period, Clarke suffered poor health. Torn between the immediate need to support her family and the desire to launch a career that would bring her greater satisfaction and financial stability, she thought of starting a school of her own but could not find a suitable location; she considered portrait painting, a lucrative business, but felt she needed more study Meanwhile she continued to worry about the family’s obligations. According to the Clarkes’ financial records, Anne contributed $200 toward her father’s mortgage in October 1819, and she continued to pay down the debt until it was cleared in the 1820s.

After he had studied with Anne for a year, Frederick was sent home. From time to time, the two sisters visited their brother George in Philadelphia, where, desperate for a stable teaching job, Anne finally moved in late 1821.

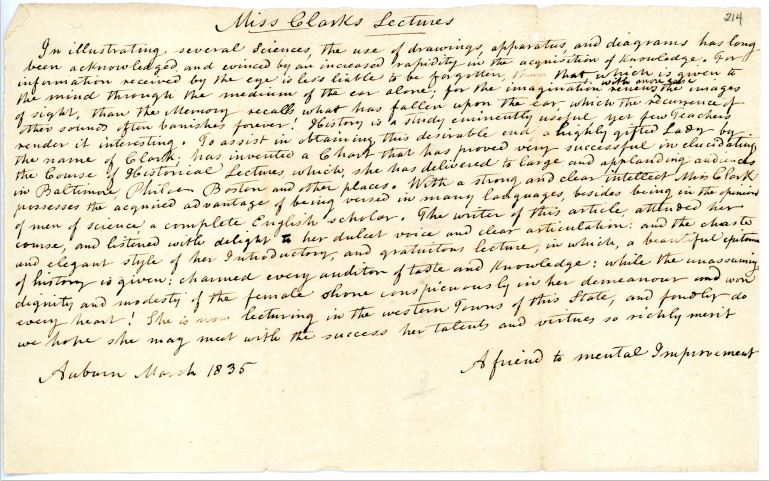

Anne’s choice about next stage of her career was, however, bold. Inspired by Philadelphia’s active lecture culture, Clarke, thirty-four years old, wrote to her father in February 1822 that he should not be surprised to see her name in the papers. She planned to imitate the example of her new friend, the American geographer William Darby (1775–1854), who lectured and taught in Philadelphia. Because most Philadelphia lecturers addressed scientific topics, Clarke felt there might be a niche for her on the subject of English grammar, and Darby offered her use of his classroom.

Philadelphia’s lecture culture was thriving in the early 1820s and, in contrast to writing for publication, was a speedy way to make money. A month’s advertising in the city’s National Gazette of 1825, for example, lists nearly fifty individual lectures or lecture series, mostly in the sciences but also in English grammar and elocution, bookkeeping, and business. At the time, lecturers typically charged $5 for a series of five to sixteen lectures on a given topic over the course of a month, or between 25cents and $1 at the door for an individual lecture. With approximately thirty people subscribing to a series, an average speaker could gross $150 a month, an entire term’s salary for many schoolteachers.

Clarke’s first public address directed toward adults was a success. On 5 May 1822, she wrote to her father that on 11 March, she had lectured on English grammar “in the presence of many ladies” in Mr. Darby’s classroom. Because some of the audience could not find seats at Darby’s, Clarke found a larger venue the following week, when she lectured at the Hall of the Musical Fund Society. That audience included men, an unusual event in early national history but a reasonable extension of Clarke’s profession. The lectures had been well received, she reported, but had excited “considerable animosity” among many of the teachers of English grammar, who were dismayed that a “Lady should step forward to take their business out of their hands.”

As had been the case since she was twenty-two years old, the mainstay of Clarke’s career was teaching classes for children. At the time, she charged $10 per pupil per quarter and $5 extra for French or drawing. By September 1823, she had about thirty students, but she was simultaneously planning to boost her income by expanding her role as an educator. She wrote to her brother Hawley that she was preparing a historical lecture series for adults. She proudly noted that “I am the first female in this Country who has offered to Lecture on any subject.—and that circumstance alone ought to insure my success”

By packaging her oratory as a type of education, Clarke took advantage of a platform for addressing both sexes that women had been slowly establishing in schoolrooms and on the printed page for the previous two decades.

With an ear for technique, Clarke also studied the genre of the public lecture outside of the classroom. She wrote to her father in late 1823 that she and her sister had begun to attend a course of lectures on astronomy offered by the English schoolmaster Robert Goodacre. She was impressed by his visual aids—he used a giant transparent globe and a fifteen-foot diameter orrery, a mechanical model that displays the orbits of the planets around the sun—but she complained that he was a “miserable” public speaker. Although 500 people had attended his first lecture, she reported, “no one is attending his 2nd!”

Clarke toured extensively for the next eight or nine years. Generally staying about a month in any given city, she spoke

on average four times a week. Her itinerary suggests that she could depend on positive reports to generate successive opportunities in a specific region. Evidence from newspaper notices as well as her letters helps establish the range and duration of her travels. Anna Gertrude Brewster, whose parents may have known the orator, wrote in 1946 that Clarke traveled as far as Ohio, probably via steamship from Buffalo, where she ran a school in the 1830s and ’40s and where her brother worked as the captain of a Great Lakes trading vessel.

Beyond the literary labor of drafting her historical lectures, Clarke drew on her skills as a graphic artist. She planned to augment her speeches with historical charts to help audiences visualize the relative duration of various monarchs’ reigns. Inspired by the vogue for chronological “maps” based on Joseph Priestley’s biographical and historical charts of the 1760s, Clarke produced several poster-sized timelines, five feet long by three and one-half feet wide, representing the rise and fall of nations and empires in vertical bars. Clarke significantly improved Priestley’s infographics, reorienting the flow of time and national achievements on vertical axes, the bars painted in bold colors, much like later visual representations of dinosaur epochs in children’s books of the twentieth century. Elizabeth, then old enough to work as an assistant teacher in her sister’s school, helped Clarke prepare the charts . Based on the initial advertisements for the school she held at her father’s house in Northampton in 1810, which promised education with “charts and maps” Clarke had been using visual aids in her teaching for over a decade. Now integrated into her lectures, the charts were frequently touted in the press as modern pedagogical inventions. A colored chart mapping the succession of the kings of Judea remains extant in her papers at Historic Northampton. Several of the larger charts have been stored in the attic of her sister Elizabeth Shaw’s house in Plainfield, Massachusetts (where they have lain forgotten for 150 years). Confident of their value, Anne filed a copyright application

in Philadelphia on 2 July 1825 and circulated a subscription to publish them.

Although Clarke had experimented with public lecturing in 1822, she formally debuted a commercial series of lectures in Philadelphia in late December 1823. She wrote to her father after her fourth lecture to say that they were going very well. Afterward, she seems to have returned to teaching for a year, during which she prepared more lectures.

She offered two more public courses in Philadelphia in 1825… She advertised the third series in advance in the National Gazette (7 October 1825) and charged $5 for the course of lectures. The principal text of her advertisement remained largely consistent over the next seven years: “Miss Clarke . . . will give a course of Historical Lectures in this city, comprising the interval from the Creation to the termination of the American Revolutionary War in 1783.” As was customary for lecturers of her day, she offered the first introductory lecture for free.

She would repeat this split presentational format in most cities over the ensuing years, initially renting public lecture halls to promote her courses to a large audience and then, for economy, using local schoolrooms to finish out the course of lectures.

As demand for her lectures increased over the years, Clarke sometimes broke her lecture series into two parts: one from the Creation to the Reformation; the other, on modern secular history, focused on America. None of the pre-Columbian lectures, beyond a few paragraphs, have survived in her papers, but there are about twelve extant lectures and lecture fragments on secular history, ranging from Columbus and the Spanish conquistadores through the American Revolution and histories of individual states—about 30,000 words in all. The historical lectures on the Americas are strongly antislavery, and they celebrate resistance to European authority in both North and South America as aspects of a single anticolonial movement, an idea frequently expressed in early 1820s North American newspaper coverage of South America. Clarke took advantage of recent publications to discuss Indian uprisings against the Spanish in Peru in 1780–81, and she vehemently criticized the Pequot War as a great reproach against the humanity of the colonists. Her lectures on the Revolution emphasize the patriotic exploits of women such as Lydia Darragh and Emily Geiger. “

On Ms. Clarke’s use of the ‘magic lantern’ Professor Granter writes, “Despite her concern that local social norms would restrict her success, Clarke made a large investment in her budding career just before she took it on the road. On 2 December 1825, after concluding her fall lecture series in Philadelphia, Clarke purchased a magic lantern, also called a phantasmagoria, and seventy-one colored glass slides from the Chestnut Street store of John McAllister and Son, a manufacturer of whips, canes, and spectacles. She paid $88.75 for the kit, including the slides, and kept the receipt for the rest of her life, probably as a token of the bold gamble she had taken on her vocation.

The financial recompense for Clarke’s touring was significant. Her records of the late 1820s demonstrate that in addition to helping to pay off her father’s mortgage in regular installments ranging from $60 to $100, she secured a $500 quitclaim by 1827 on a property for herself. In the late 1830s and early 1840s, she invested her surplus in bank stock and, with her brother Frederick, in Buffalo-region real estate ventures. By the time she died in August 1861, Clarke’s Northampton land holdings were valued at $5,825 and her personal estate at $3,226, which, as stipulated in her bequest, were liquidated and divided principally among her siblings and their children.“

Ms. Clarke was born on the 4th of July in 1788 in Northampton, Massachusetts. She died on August 15, 1861, in Southampton, Massachusetts, at the age of 73, and is buried in the Bridge Street Cemetery, Northampton. Ms. Clarke was never married and had no children.

To see the collection of Ms. Clarke’s slides click here.

To read about the Hawley family click here.

To learn more about women’s changing role in the mid-1800s read this interesting article, Changing Ideals of Womanhood During the Nineteenth-Century Woman Movement by Susan M. Cruea