The Botanical Arts

The Shaw and Hudson families took a great interest in the flora and fauna of the Plainfield hills, as evident by their vast collection of nature books, journals of their gardens, and especially with the company they kept. Letters show that they often corresponded with many of the leading botanists of the time.

The house is filled with botanical drawings, scientific instruments, and writings of the many outings they took.

The following are excerpts from The Romances of a Country Doctor, a paper read at the annual meeting of the Northampton Historical Society at the Unitarian Church, Northampton, on October 7, 1947 and Plain Tales from Plainfield or The Way Things Used to Be, 1962, both by Clara Elizabeth Hudson. Ms. Hudson was a granddaughter of Dr. Samuel Shaw and the last surviving relative to live in the Shaw Hudson House.

Click on photographs to see a larger image. All blue text is hyperlinked to pages with more information.

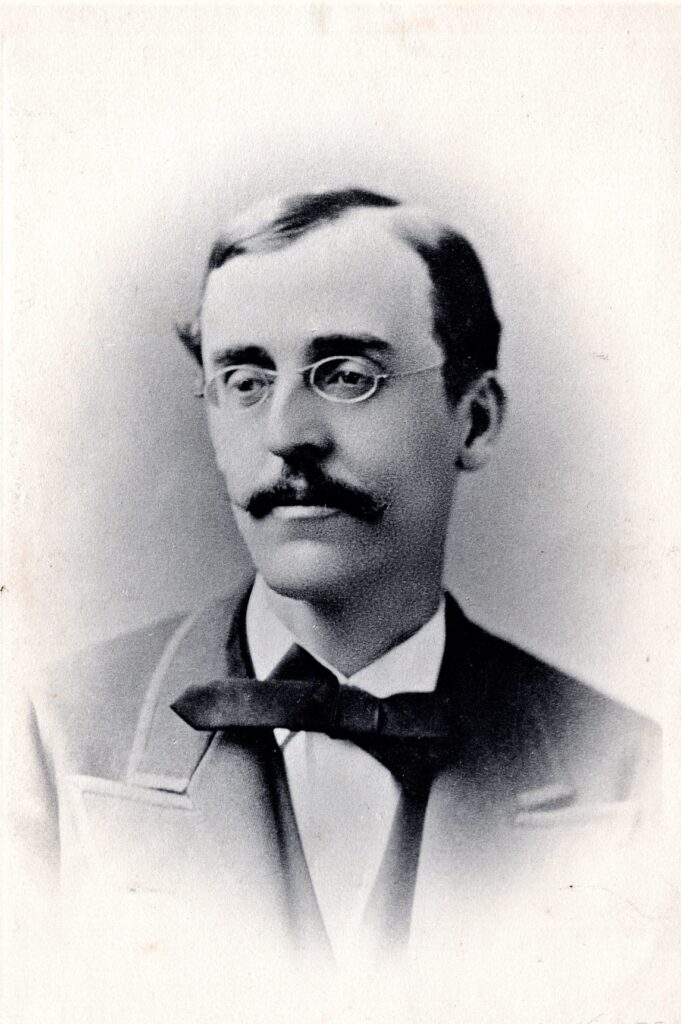

Charles Lyman Shaw 1842 – 1902

“My uncle, Charles Lyman Shaw, loved the Hampshire hills near Plainfield. With his metal vasculum to hold botanical specimens slung over his shoulder, he took many long tramps. One friend, a Springfield doctor who used to visit him, liked these walks also. The doctor was short and fat; my uncle rather tall and thin. The combination reminded one of a period and an exclamation point!

Two other walking pals were a father and son from Amherst whose names I do not remember. The father was a former professor, the son a rather frail bachelor. (We believe the professor mention here was the prominent scientist Edward Hitchcock)

With my uncle and friends we enjoyed many a hayride to Moore’s Hill in Ashfield, where we picnicked, and to other spots from which fine views could be seen. The professor may have been the authority who identified the scratches plainly visible on some rocks in a high-lying Plainfield Pasture as having been made in the glacial age. As my uncle died in 1902, and as I have not hunted up these scratches since then, I do not remember their exact location, but I do know that their general direction was north and south.

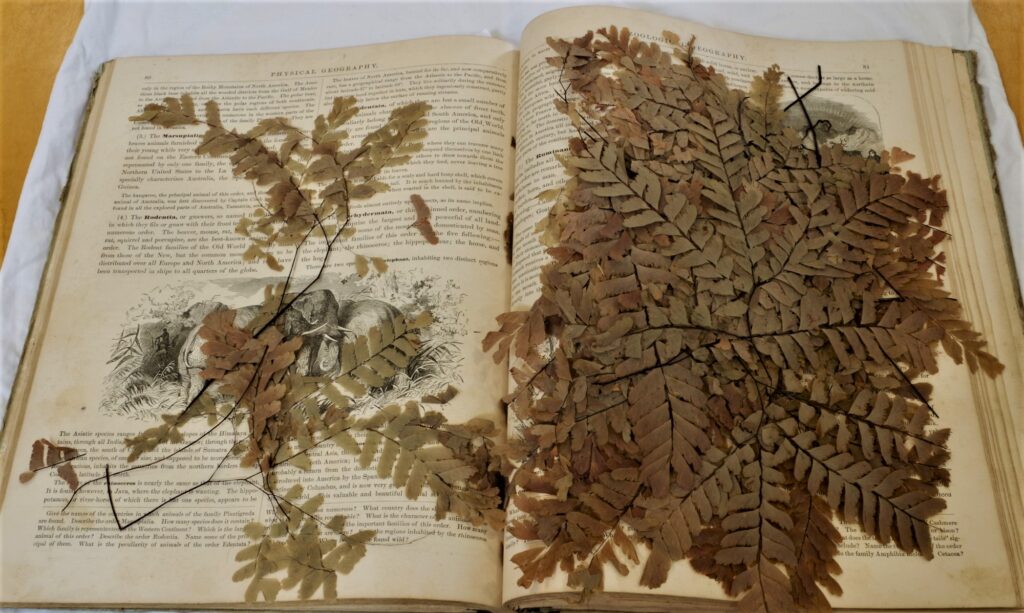

My uncle often brought home interesting botanical specimens which my mother and I sometimes identified with the aid of Gray’s manual. I remember that one book by Gray was entitled, How Plants Grow. As a child I read the title as How Plants Grow Gray. I didn’t know of any plants that grew gray except lichens and I thought the title most peculiar.

One day while a friend and I were wandering around our family’s pasture we came across a curious little plant which I had never seen before. My friend thought it was a rare species of grape fern called moonwort, but it was probably the little grape fern which is known to grow in Massachusetts. As I remember it, the plant was not over five inches high.

Among other unusual things which my uncle happened upon was an isolated grave stone in a pasture, marking the burial place of a woman who had died of smallpox.

My uncle had many topographical maps of Massachusetts, and with his field glass he identified mountains at a distance and knew their names and elevations. Some of the local farmers said that Mr. Shaw was the first one to make them realize that they had mountains.

To my uncle, Charles Lyman Shaw, I owe much of my interest in factual books. Until I went to Barnard College in New York City, he was my only school teacher, and an excellent one. I have never attended either grade or high school, and until I went to college I had never been in classes with girls. Reciting in a class of fifty girls often brought tears of nervousness to my eyes, whereas reciting with a dozen or more boys hadn’t disturbed me at all.

Several of the boys in our “crowd” were preparing for college but I was the only girl. So mother and I called on the dean o£ Barnard College. She advised my taking the preliminary examinations. I failed in Greek but passed it a year later and entered college without any conditions.“

A curious find in a draw of the Shaw-Hudson house, wrapped in tissue and stored in an old hosiery box, was a series of pierced or “skeleton leaves”. Despite intensive research, we know little about them. Some have suggested that they are from Europe, Switzerland, perhaps, and were a tourist item, as we know several of the Shaw/Hudson clan traveled extensively.

In the book, Phantom Flowers: A treatise on the Art of Producing Skeleton Leaves(1864), published by J. E. Tilton, it states, “…in commenting on the progress of the arts, avers that leaf bleaching has been known from time immemorial, in Europe and Asia, by those families in which botanical tastes have been hereditary. In Great Britain and on the Continent, as well as in this country, among the quaint old curiositcs to be found in the houses of retired sea captains, specimens of skeleton leaves are to be found…” Perhaps Dr. Francis Shaw picked these examples up on one of his many voyages. To see a gallery of these amazing leaves click here.

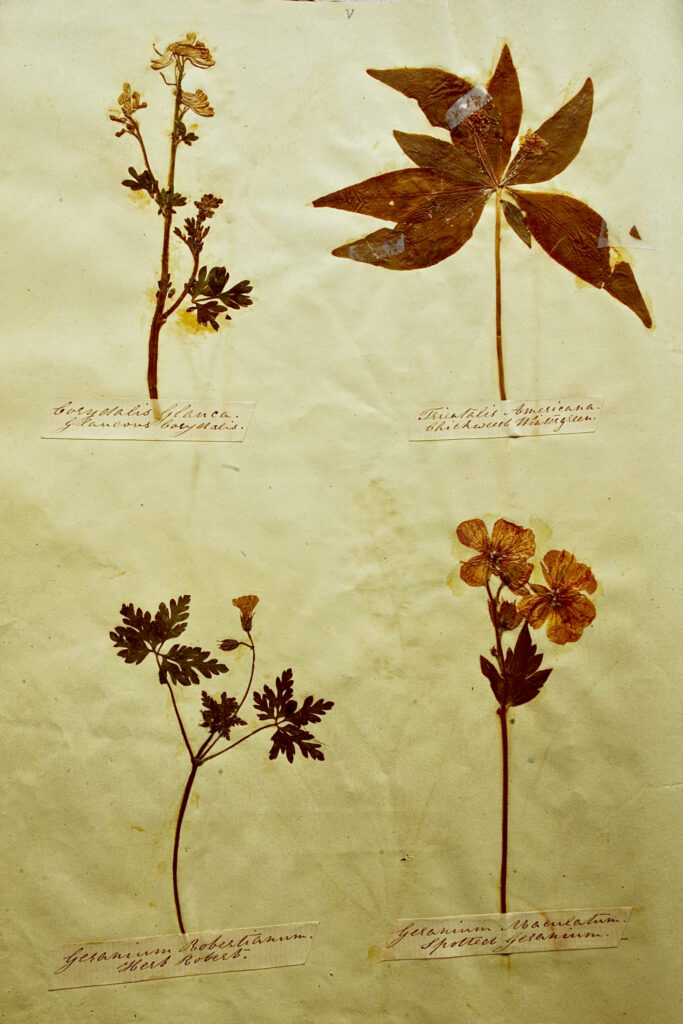

Samuel Francis Shaw 1833 – 1884

The Plainfield Historical Society was lucky enough to have been given a truly remarkable herbarium that is connected to the Shaw Hudson house. Created in 1854 by Dr. Shaw’s first son, Samuel Francis Shaw, will studying medicine at nearby Williams College, the herbarium is a collection of dried plants and flowers labeled with their scientific names.

To view Dr. S. Frances Shaw’s complete herbarium Click here. To see a gallery of the entire herbarium click here.

To see more on the Shaw’s connections to botany and geology check out our online exhibit, Plants on Paper: Two Centuries of Collecting, Studying, and the Art of Flora in Plainfield, Massachusetts.