Oxen Demonstration by D.J. Clary

With a backdrop of colorful fall foliage, local resident, D.J. Clary brought two of his oxen to the Shaw Hudson House to give a demonstration of how oxen played a pivotal role in the development of early American agriculture and how they are still used today on many farms in the area. D.J. first became interested in becoming a “teamster” as a child. “My grandparents had a farm in Conway, MA, that has been in my family since the Revolutionary War era.” “They received the land in lieu of a cash payment for service in the war.” This was a common practice at the time, with many settlers to our region having received payment in land. Both before and after the Revolutionary War, money was needed to pay off loans and both England and then later, the United States’ federal government awarded bounty lands or land grants to citizens and soldiers for services rendered. In its simplest form, this involved the exchange of free land for military service. States also put up land for auction to land speculators as a way to raise revenue and indeed, Plainfield itself, had its beginnings this way, being sold at a public auction on June 2, 1762, as part of Plantation No.5. But back to our oxen!

A frequent visitor to his grandparents farm, D.J. first became interested in working or draught animals as a youngster, but found the draft horses, ” a little scary and unpredictable!” His interest turned to oxen about ten years ago, when an opportunity he couldn’t pass up came his way and he acquired his first oxen. He found the oxen “much more docile and slower than the horses that would come thundering down the road,” and a passion for these behemoths began, that would only grow over time.

Today, D.J. has several teams of oxen that he brings to shows, demonstrations, and teamster’s challenges around New England. He also competes in oxen pulls, which is familiar to anyone who has visited the Cummington Fair. He finds them great companions and uses them on his own farm to plow and haul wood. It is not uncommon to see D.J. cruising through the center of Plainfield with his oxen and cart, usually hauling a group of laughing kids! As D.J. said, “It’s never too late to have your happy childhood!”

Let’s learn a little more about these magnificent animals. As always, click on any of the blue highlighted text to link to more information.

Milkin’ Shorthorned Durham Oxen

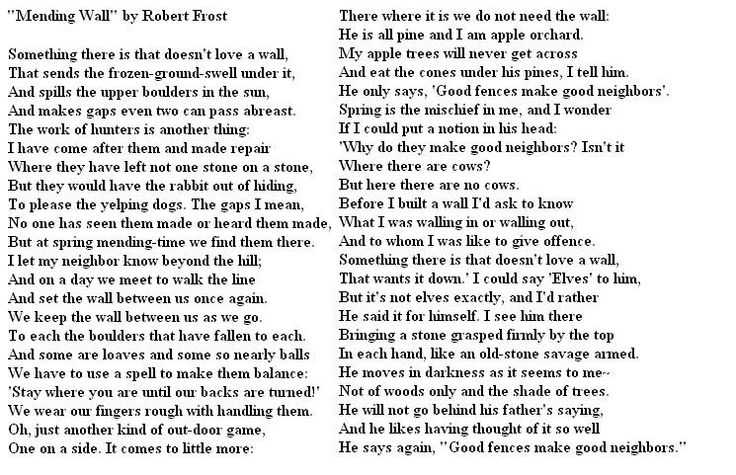

Weighing in at approximately 2,200 lbs each, Dick and Eddy, both nine years old, are Shorthorn Durhams, throughout history, one of the most popular breeds of cattle. An ox is actually nothing more than a specially trained dairy or beef steer that has reached the age of about five. Oxen are not a breed of cattle but rather steers – adult, male bovines that have been castrated. Male cattle are selected because they grow to be larger than the females, and cows are more valuable for their milk and their ability to produce calves. Depending on age, sex and breed, these beasts can weigh 1,500 to 3,000 pounds and pull an amount equal to or greater than their own weight. They were sometimes called the “poor man’s power” back in the 1800s when oxen’s economical nature enabled them to play an important role in literally leading the United States’ expansion westward to millions of fertile, unclaimed acres. As a matter of fact, the word “acre” itself was once defined as the area that one pair of oxen hooked to a plow could till on the Summer Solstice – the longest day of the year.

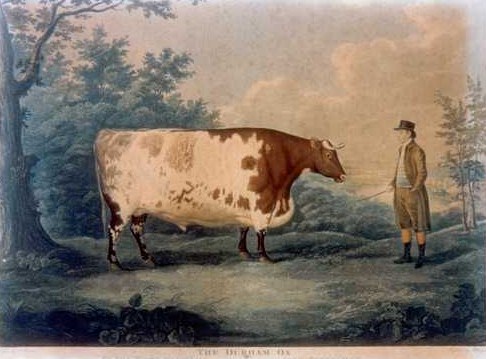

Etching of the Durham Ox by John Boultbee (1753–1812)

The Shorthorn was historically called the Durham because it originated in the county of Durham, England. Imported Dutch cattle were crossed with native stocks and selected for performance in both meat and milk production. The breed became known early in the 1800s, especially through a traveling promotional exhibit of the famous “Durham Ox.” The Ox, calved in 1796, weighed over 3,500 pounds at ten years old and through his extensive travels he brought much acclaim to the breed. Shorthorns were first imported to America in the late 1700s, with the largest number of cattle brought in after 1820. The breed was initially concentrated in Ohio and Kentucky, a region rich in grass and corn to feed cattle, but by the end of the1800s they were spread throughout America. The Shorthorn was valued for its dairy and beef qualities and also used as a draft animal.

These “gentle giants” each consume 3/4 a bale of hay and 18 lbs. of grain every day in the winter and about half that amount during the summer months. They are forage efficient, hardy, long-lived, and productive, with calm dispositions and strong maternal instincts.

Both Dick and Eddy are castrated males, thus having bigger frames and stronger bones, making them ideal for hauling stones and logs – jobs much needed by early settlers of New England. Durhams have large protruding hips that allow them to kick in any directions, unlike mules and horses, “so you sure have to watch out when you come around back of them,” chuckled D.J..

Since they have cloven feet and can not stand on just three legs, they are not easy to put shoes on, so they are seldom shod, except when they work in icy conditions. Although both horses and oxen benefit from wearing shoes, oxen are less likely to develop foot problems by going unshod over long distances.

D.J. stated that he normally can get twelve years of work out of each ox, depending on how hard they are worked. Since the 1600’s, teams of oxen have been used in plowing, logging, moving stones for clearing fields, transportation and even for moving houses. “Oxen would haul apples to the cider house where the driver would usually receive a well earned cup of cider afterwards,” stated D.J..

Oxen were a bargain among draft animals in the 17th, 18th and 19th century, and they still are, given their relatively low initial cost, the ability to work long hours, inexpensive equipment and a lengthy lifespan. In her book, Creatures of Empire: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America, Virginia DeJohn Anderson writes, ” For the colonists, they not only provided a source of food — and a link with English traditions of animal husbandry — but were the only meaningful form of agricultural capital outside of land itself. Oxen, for instance, were not only useful in clearing and cultivating farmland, but “proved equally valuable for other productive endeavors” such as shipbuilding. One report from 1687 tells of 36 ox teams — 72 animals — hauling an enormous white pine to a New Hampshire sawmill to be made into a ship’s mast.”

Since cattle are hardier than horses, they can also get by with a less refined shelter. When not needed for chores, oxen could be turned out into the woods to forage for themselves and rounded up again when there was work to be done. Not only could oxen out-pull horses when it came to drawing a wagon, but the oxen were also able to thrive on poorer grass and brush instead of relying on the scarce and expensive grain required by horses. And of course, because they are beef cattle, oxen can be eaten. That’s why it should be no surprise that the most used draft animal in the world remains the ox.

While many different breed of oxen were used throughout New England the Durham remained the most productive, even being used for milking and meat production.

In the late 19th century and beyond, oxen began to be replaced by tractors, making western expansion easier but oxen continued to play an important role on the farm. There has been a revival of breeding and working heirloom breeds of oxen, with many folks choosing to use oxen on their working farms.

Today, driving oxen can almost be considered a sport with teams competing at local fairs throughout the United States. There are even obstacle course competitions. In the summer and fall, D.J. and his teams of oxen travel throughout New England enlightening many to the virtues of oxen through his enthusiastic demonstrations. It is obvious that there is a strong bond between D.J., Eddy, and Dick!

To learn more about oxen click on the links below:

Oxen: Engines of the Overland Emigration

The Introduction of Cattle into Colonial North America

Creatures of Empires: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America

Training and Tack

D.J. Clary brought along many of the “tools of the trade” he uses when working Eddy and Dick and demonstrated how they were used.

Neck Yokes – First up was the neck yoke. Neck yokes give oxen greater flexibility and maneuverability than head yokes used in many different cultures, which gives the teamster less control over the animals. The yoke sits atop the middle of the animal’s neck, with curved bows wrapping underneath to hold the yoke in place. Neck yokes require oxen to push with their shoulders, necks and chests rather than with their heads. This style is an English tradition that was exported to the United States and Australia, where it is still in use today. Ox yokes, made of wood with a few iron fittings, could be easily made with simple tools and were well within the capabilities of the pioneer farmer. Horse harnesses, by comparison, were relatively fragile and harder to make and repair. The oxen are held together not with a harness, but by a wooden yoke consisting of two main components. The yoke itself rides on top of each ox’s neck in front of his shoulders. It is made of such woods as cherry, curly maple, elm, oak or yellow birch. D. J. stated that elm was the best wood, but because of the Dutch Elm Disease that all but eliminated all the elm trees in New England in the mid-20th century, today they are made of other types of wood. The yoke that was used for this presentation was made in Worthington, MA. Properly maintained yokes can last virtually forever if they are coated with a waterproof finish and the bows are kept oiled and handled correctly.

Ox Yokes: Culture, Comfort and Animal Welfare by Dr. Drew Conroy Professor Applied Animal Science, University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire

Commands or Teamster Terminology – “There are basically four or five commands that a team of oxen needs to know,” said D.J., “whoa, come up, back, stand and gee, with all the rest of the commands being basically combinations of these terms.” The terminology for working oxen is similar to that used with horses and mules, with some regional differences in calls.

While most cattle are none to happy to back up, it is necessary for hitching them up. “It’s against their instinct to blindly go backward!” said D.J., so he sometimes has to prod them along with terms like “set in” or “rump in” and “set out” or “rump out” when hitching them up. The relationship that D.J. has with his oxen, along with voice tone and body language also add to controlling his team. D.J. fondly remembers bringing Eddy and Dick home in his car when they were just two weeks old and he has been working with them ever since.

Bob Woodruff of West Tisbury has owned and worked with oxen over the years; Bob recommends starting to train oxen when they are still calves – the sooner the better. When they are smaller they’re easier to move around and they tend to be more submissive when they’re young.

“You begin by putting a halter on them,” explains Bob, “and lead them around with your hand close to their chin. Then you start to get them used to the commands: ‘Haw – good boy, Billie – haw, haw.’” Haw is the command for turning left and as you say it, you pull the ox’s head to the left and he’ll naturally follow. Bob gives the commands firmly, but there’s also affection in his voice. The idea is to work with the animal, not against it.

After a few days – each ox learns at its own pace – the animal becomes used to the halter or, as they say, “halter-broke.” If you have two oxen, this is a good time to put a yoke on them, not only to get them accustomed to the gear, but also to working with one another. You can start to get the oxen acclimated to whip commands as well.

The basic commands for driving oxen are: haw, gee (turn right, pronounced “jee”), back, come up (move forward), whoa, and stand (stay). The driver stands to the left of the animal and as the oral command is given, the whip (or a goad stick) is used for emphasis. As Bob puts it, “It’s used more as a guide than a punisher, but at times you may have to use some force.”

So if the command is “haw,” the driver taps the “off ox” – the one farthest away from him – on the right side of the chest, the face, or the neck so it will turn away from the tap and go left. By then tapping the “nigh ox,” the one nearest the driver, on the left rump, that ox will move left as well.

To move the team to the right, the process is reversed. The nigh ox is tapped on the left chest and the off ox is tapped on the right rump. To move forward or backward the oxen are tapped fully from behind or on the chest, depending on the command. Bob says it can take a couple of years to train an ox – to get him “handy” – so patience is a requisite. And while it’s possible that a team can be eventually controlled strictly with voice commands, that is indeed rare. – Geoff Currier, Vineyard Gazette

Tip Cart – One of the more familiar implements D.J. had on display was this ox cart – a “tip” cart as he called it. “This is the 18th century version of a dump truck!”

This cart would be of the utmost importance to early New Englanders, carrying loads of firewood, charcoal, crops, people – anything that needed to be hauled from one place to another. Its small size made it easy to back into a woodshed, barn or cellar and it required very little in maintenance.

As a side note, in Costa Rica, ox carts (carretas in the Spanish language) were an important aspect of the daily life and commerce, especially between 1850 and 1935, developing a unique construction and decoration tradition that is still being developed. Costa Rican parades and traditional celebrations are not complete without a traditional ox cart parade. In 1988, the traditional ox cart was declared as National Symbol of Work by the Costa Rican government. In 2005, the “Oxherding and Oxcart Traditions in Costa Rica” were included in UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bullock_

Working Carts and Wagons: Colonial Williamsburg

Ox Carts A National Symbol in Costa Rica

Logging Sled – The logging sled was used to haul large logs out of the forest. After the sawyer cut down the tree, and sawed off the branches, the twitching began. D.J. explained that, “Twitching was hauling the logs to the saw pit.” “Oxen are much more maneuverable than horses between trees in the dense forests of New England,” and it was not uncommon for teamsters to “rent” out their teams for extra income during logging time. Logging was usually done in the winter, when there were no leaves on the trees, the logs were easier to haul and they remained much cleaner, with less dirt and bark from dragging them on the ground.

D.J demonstrated how the oxen, once chained to a large log, would pull the log onto the sled and then, when hitched to the sled, would pull it through the woods. “Working in the woods with these guys is so much fun…and much more personal than a tractor!”

The Transportation of Logs on Sleds by Alexander Michael Koroleff and Ralph C. Bryant

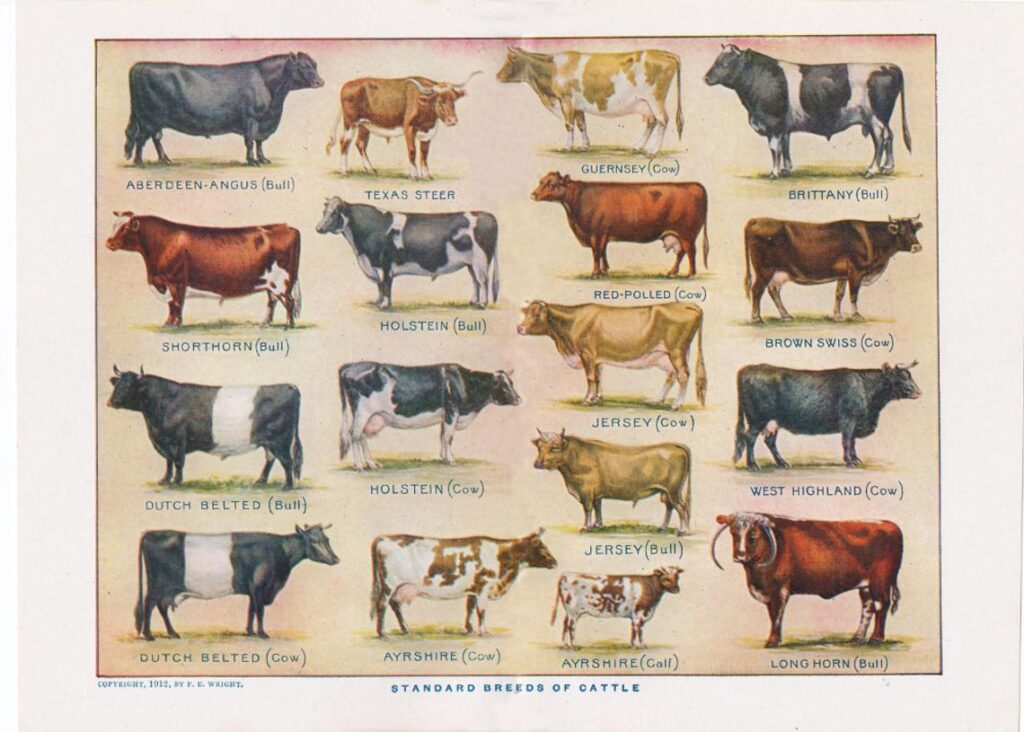

Stone Boat – Anyone who has tried to till a garden in Plainfield would appreciate this tool! The stone boat or sled was vital in removing the many stones, ranging in size from pebbles to boulders, in the fields throughout much of New England. Farmers would remove the stones and haul them to the perimeter of their fields and make the stone walls that all but define New England. The US Department of Agriculture estimates that there are 240,000 miles of stone walls in New England – that’s four times around the circumference of the Earth! Even if a farmer thought he had all the stones out of a field, over the winter the frost heaves would belch out more stones and the farmer would have to start all over again. Welcome to farming in New England!

D.J. demonstrated how the stone boat was hitched to the team of oxen and then had them haul a few large stones across the grass. While D.J.’s stone boat is made of metal many were made of wood and metal.

Written in Stone by Joe Rankin

Stones that Speak: Forgotten Features of the Landscape

Even Robert Frost, New England’s most well known poet, understood the torments of New England’s stone walls, as he laments in one of his most famous poems, Mending Fences.

The Geology of Colonial New England Stone Walls

A big thank you to D.J. Clary and family for donating their time and energy on a beautiful afternoon. D.J. is a natural teacher and we all enjoyed learning about and sharing his passion for these beautiful creatures, and especially for tying the present to the past.

“When I am working with these oxen I feel I am experiencing what my ancestors went through and makes me very connected to them,” said D.J.. “This is not the same as reading history, watching it on T.V., or seeing it in a museum,” he said, “you’re really living it!”

To learn more about working teams of oxen click on the links below:

The Magnificent Oxen of the Centennial Farm

Oxen No Has-Beens When It Comes to Hard Pulling

Fantastic description!

Wonderful outdoor event! So much was learned from DJ CLARY and now this great write up.

Thank you, Lori

This is awesome and very informative thank you so much ❤️